Section 9.2 Incident Response

As you study this section, answer the following questions:

- What is the purpose of a tabletop exercise?

- What are the three teams in security testing?

- What is the incident response life cycle?

- How are playbooks used in incident response?

- What should an incident response policy include?

- When does the incident detection phase begin?

In this section, you will learn to:

- Respond to a security incident

- Perform incident response reporting

The key terms for this section include:

Key Terms and Definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Tabletop exercise | A type of incident response planning activity that does not involve a mock incident or full incident simulation. During tabletop exercises, organizations bring together the personnel who would respond to an incident, often in a simulated setting, to test the effectiveness of their communication and response plans. |

| Red team | Skilled hackers that use their skills to attack a specified target to test for vulnerabilities. |

| Blue team | The defenders of the network. They use their skills to configure protection devices, scan and monitor the network for unusual activity, and do what they can to stop it. |

| White team | This team is comprised of managers, assessors, and other technical and non-technical staff. Their purpose is to design the rules of engagement, organize teams, and adjudicate the exercise. |

| Incident response planning | Helps organizations create a plan to identify, investigate, and respond to potential threats and incidents. |

| Playbook | Documentation that defines the steps an organization will take to respond to a security incident. |

| Incident response policies | Statements of the organization's expectations and procedures for responding to security incidents. |

| Stakeholders | Any individual, group, or organization that can affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by a decision, activity, or outcome relating to an incident. |

This section helps you prepare for the following certification exam objectives:

| Exam | Objective |

|---|---|

| CompTIA CySA+ CS0-002 | 1.3 Given a scenario, use appropriate tools or techniques to determine malicious activity

2.5 Explain concepts related to vulnerability response, handling, and management

3.2 Given a scenario, perform incident response activities

3.3 Explain the preparation and post-incident activity phases of the incident management life cycle

4.1 Explain the importance of vulnerability management reporting and communication

4.2 Explain the importance of incident response reporting and communication

|

| TestOut CyberDefense Pro | 2.2 Detect threats using analytics and intelligence

4.1 Manage security incidents

4.2 Manage devices

4.3 Analyze indicators of compromise

|

9.2.1 Incident Response Training and Testing

Click one of the buttons to take you to that part of the video.

Risk Training 00:00-01:06 One constant when we evaluate system risk is a perpetual need to maintain a well-trained staff. Not only should an organization's cybersecurity staff be competent, but they also require training in offense as well as in defense to help them get into the minds of potential threat actors. To make this happen, security teams often conduct practice exercises to test their knowledge and abilities in attack prevention.

We use different teams for different functions. The red team is the offensive team. Its job is to try and break through defenses and obtain access to an organization's network. The blue team is the defensive team. Its job is to defend the network. Members try and prevent an attack before it occurs. The white team has the unique job of adjudicating these mock attacks between the red and blue teams. They can perform their role during a true mock attack or, alternatively, through hosting tabletop exercises. This is a mock attack that's carried out in a meeting where both sides discuss how a given scenario might be played out. It's the more theoretical of the two exercises.

Red Team 01:06-01:48 As the red team is the offensive team, it takes on the threat actor's role and attempts to gain access to the organization's network resources. Typically, the red team is comprised of experienced ethical hackers. Ethical hackers are trained with hacking tools and techniques. The attack team might also include penetration testers that find weaknesses in the system's outer defenses. Once found, the goal is to do everything possible to breach those defenses. Overall, the red team's primary mission is to gain access to internal resources, like network servers or individual workstations. This role is often outsourced, since the internal source is well-informed about the organization's defensive posture beforehand.

Blue Team 01:48-03:21 As the network defenders, the blue team actively monitors the network to ensure that their defenses haven't been breached and that there's no active attack. The blue team jumps into action if they detect an anomaly or a security alarm goes off. There are a few ways these warnings might come in. When a firewall detects a possible breach or configuration change, it usually sends a warning message to the team with the details. An intrusion detection system, or IDS, sounds a system alarm. An intrusion prevention system, or IPS, takes the more drastic step of attempting a shutdown.

A honeypot is a device that's used to lure an unsuspecting attacker to aimlessly explore. The device itself mimics a live system. But in reality, it's a trap that accounts for the attacker's tools without actually exposing anything sensitive. In addition to hardware devices, the blue team uses software tools to try and figure out what might be happening. The team might use a packet analysis tool, such as Wireshark, to capture packet traffic traversing the wires. Endpoint detection uses AI to identify potential malicious activity, automate responses, and ease threat hunting. This is all a manual process. It's especially beneficial when you're looking for internal attacks.

Logs are an often-overlooked diagnostic tool. Log aggregation tools like Splunk are used to combine log files from various devices, such as servers, routers, and switches. A log aggregation tool makes log files searchable so that an analyst can review them and look for abnormal behavior and attack signatures.

White Team 03:21-03:47 The white team is comprised of staff that oversee compliance, management, logistics, and more. They may or may not be technical staff, but they must be knowledgeable about the security process and how the teams operate. The white team puts everything together and defines the exercise and rules of engagement for the teams to work within. In the end, the white team is responsible for conducting the ultimate risk assessment and for carefully monitoring the activity's progress.

Tabletop Exercises 03:47-04:23 Now that you understand the different teams, we can discuss tabletop exercises. In these exercises, the white team defines a theoretical scenario and specific criteria to evaluate the red and blue teams on. They're given the criteria and rules of engagement beforehand, and then they take some time to strategize. Finally, they all come together and work through the exercise by discussing the what, when, where, why, and how of their respective plans. This is an exercise conducted in a meeting, not on actual equipment. The white team evaluates and scores the teams based on who presented a better solution.

Summary 04:23-05:01 That's it for this lesson. In this lesson, we discussed the requirements for the different risk training teams. This training provides safety considerations for an organization's exposure and risk. The red team assumes the attacker's role and uses hacking techniques to defeat system protections. The blue team defends the network and uses their skills and experience to prevent exposure and to stop the red team's advances. The white team is the decision-making team that designs tabletop exercises and rules of engagement to adjudicate exercises, whether they be on actual equipment or just conceptual.

9.2.2 Incident Response Training and Testing Facts

Training for possible threats helps keep everyone prepared for an eventual attack. Practicing attack scenarios helps find weaknesses and identify potential vulnerabilities.

This lesson covers the following topics:

- Training

- Tabletop exercise

- Testing

Training

The actions of staff immediately following the detection of an incident can have a critical impact on successful outcomes. Effective training on incident detection and reporting procedures equip staff with the knowledge to react swiftly and effectively to security events. Incident response is also likely to require coordinated efforts from several departments or groups, so cross-departmental training is essential. The lessons learned phase of incident response often reveals a need for additional security awareness and compliance training for employees. This type of training helps employees develop the knowledge to identify attacks in the future.

Training should focus on more than just technical skills and knowledge. Security incidents can be very stressful and quickly cause working relationships to crack. Training can improve team building and communication skills, giving employees greater resilience when adverse events occur.

Tabletop Exercise

A tabletop exercise evaluates the effectiveness of incident response procedures. The tabletop exercise focuses on a particular objective to determine whether all parties involved in the response know what to do and can work together to accomplish the desired outcome. The individual leading the tabletop exercise outlines a specific (imaginary) event to which the team must respond. During the response, the activity leader will expand on the scenario by adding new details or an additional event/consequence to which the participating teams must adapt.

For example, a tabletop exercise might use a large-scale ransomware infection as a scenario and challenge the leadership team to manage the event. Information is provided to the leadership team to parallel how the event would unfold during a real crisis. As the team makes decisions, the facilitator provides realistic consequences and responses. Often, the team is challenged to manage a "plot twist" while dealing with a different issue, such as creating a press release in response to an urgent media request for information. Tabletop exercises can be very effective when led by an experienced facilitator.

Testing

There are few ways to prove beyond a doubt that incident handling procedures are robust enough to cope with significant breaches or DDoS attacks, but the best approach is testing. Testing comes with challenges, as arranging a test to simulate an attack is costly and complex. There are various test methodologies, including tabletop exercises to analyze an incident scenario or compare controls against a framework model, but the most accurate is penetration testing (pen testing). In this type of test, a team of penetration testers attempts an intrusion using a specific scenario devised using threat modeling. Incident responders use established procedures to detect and repel the attack.

Leadership can initiate testing in this way with or without the knowledge of the incident responders. Excluding incident responders from the plan can evaluate their effectiveness, although this can be a humbling experience for all but the most battle-hardened incident responders.

There are three primary teams for this type of testing, and they are often referred to using the following names:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Red team | These are skilled hackers that use their skills to attack the specified target. Often, this team is outsourced since most internal staff are aware of internal controls used to block access. |

| Blue team | These are the skilled defenders of the network. They are the defensive side in the exercise. They use their skills to configure protection devices, scan and monitor the network for unusual activity, and do what they can to stop it. |

| White team | This team is comprised of managers, assessors, and other technical and non-technical staff. Their purpose is to design the rules of engagement, organize teams, and adjudicate the exercise. |

9.2.3 Incident Response Overview

Click one of the buttons to take you to that part of the video.

Incident Response Overview 00:00-00:10 In this video, I'm going to talk about how to respond to security incidents that could happen within your organization.

Incident Response Plan 00:10-01:20 A security incident is an event or series of events that result from a security policy violation and that has adverse effects on a company's ability to proceed with business. Security incidents can include employee errors, unauthorized employee acts, insider attacks, external intrusion attempts, virus or harmful code attacks, or unethical gathering of competitive information.

Incident response is the actions you take to deal with an incident during and after it occurs. Prior planning helps people know what to do, and all company leaders should be familiar with the incident response plan. At least one member in every department should be trained to recognize abnormal activities, suspicious behavior, unauthorized activity, and irregular patterns in employee conduct. When an employee discovers an incident, he or she should recognize and declare it, preserve any evidence, and contact the appropriate personnel.

Incident response should identify the problem, investigate how it occurred, and implement forensics to preserve evidence. This includes removing the incident's cause, recovering and repairing any damages, and documenting and implementing countermeasures to reduce a future attack's likelihood.

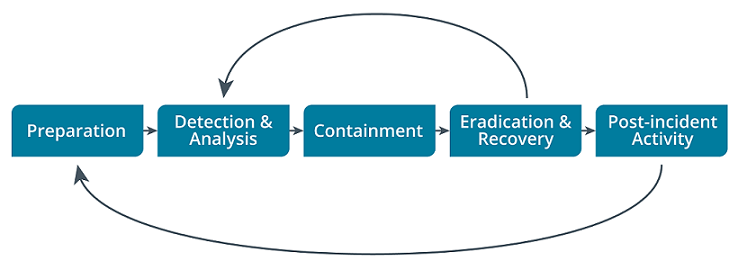

Incident Response Life Cycle 01:20-03:07 Each of these areas form what we call the incident response life cycle. There are five stages in this life cycle—preparation, detection and analysis, containment, eradication and recovery, and post-incident activity.

The preparation phase gives you an opportunity to reinforce your system so that you can bounce back in the event of a security incident. During this phase you ensure that your systems have been secured and that you have policies, procedures, and resources in place to help streamline your response.

The detection and analysis phase gives you a chance to identify an attack or an incident after it has begun. This phase also helps to determine an attack's severity.

The containment phase reduces an incident's impact. This phase's primary goal is to make sure the incident doesn't impact customers and external business partners any more than necessary. This is done by isolating affected systems and restricting communication to only trusted individuals.

After the incident has been contained, you can eradicate the source of the problem and begin the recovery process. Eradication is complete removal and resolution. This means that the root issue is resolved and all devices are fully hardened. In some instances, this could mean a full reimaging of host machines. It could also involve adjusting permissions or hardening network resources.

The post-incident phase includes two parts, which are the post-incident activity and post-incident feedback. The post-incident activity phase includes the creation of reports that summarize the incident, the response, and any recommendations for future action. During the activity phase, you also want to hold meetings to discuss lessons learned. The post-incident feedback phase includes taking the recommendations and putting them into action through security implementations, policies, and procedures.

Summary 03:07-03:27 That's it for this lesson. In this lesson, we talked about what incident response is. We also discussed the 5 phases of the incident response life cycle—preparation, detection and analysis, containment, eradication and recovery, and post-incident activity.

9.2.4 Incident Response Overview Facts

Incident response planning is preparing and developing a strategy to handle security incidents. Organizations must have an action plan to protect their data, resources, and systems when a security incident occurs. This plan includes the identification of threats, the steps to mitigate any potential risks, and the resources needed to respond to an incident. The success of incident response activities depends on the organization's ability to identify potential threats and implement standardized processes to respond to them.

This lesson covers the following topics:

- Incident response planning

- Incident response life cycle

- Response methods

- Preparing for Post-incident Activity Phases (Video)

Incident Response Planning

Incident response (IR) planning helps organizations create a plan to identify, investigate, and respond to potential threats and incidents. A well-crafted incident response plan will provide the guidelines, resources, and protocols needed to minimize the impact of a security incident and ensure business continuity. Incident response plans are crucial to protecting an organization’s assets in the event of a security incident. Without a plan, organizations risk being unprepared to respond effectively and efficiently to potential threats and incidents or being unable to minimize the damage from these events. By exposing potential risks and outlining appropriate responses, incident response planning activities help organizations maintain the security of their systems and data, protect their reputations, and minimize damages from security incidents.

Any effort to prepare for and respond to security incidents is considered incident response planning. Formal planning activities include threat modeling, risk analysis, policy and process development, testing, and simulations. These activities help identify risks and threats, assess their potential impacts, and create and implement the response plans, tools, and resources required to prevent and respond to security incidents.

Incident response planning activities are often part of the broader terms “incident response” and “incident response planning,” which also encompass responding to security incidents once they occur. This includes creating guidelines for responding to certain types of incidents, identifying the resources needed for each response, and establishing protocols for how the different personnel and groups will work together to mitigate incidents.

Incident Response Life Cycle

Incident response plans (IRP) are the actions and guidelines for dealing with security events. An incident occurs when security is breached, or there is an attempted breach; NIST describes an incident as "the act of violating an explicit or implied security policy." The NIST Computer Security Incident Handling Guide special publication ( nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-61r2.pdf ) identifies the following stages in an incident response life cycle (Containment and Eradication & Recovery were separated into different phases).

There are five stages in the incident response life cycle:

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| Preparation | The preparation phase allows you to reinforce your system so that you can bounce back in the event of a security incident. Systems should be made more resilient to attacks in the first place. This includes hardening systems, writing policies and procedures, and setting up confidential lines of communication. It also implies the creation of incident response resources and procedures. |

| Detection & analysis | The detection and analysis phase involves identifying an attack or an incident after it has begun. This also includes determining and assessing how severe it might be (triage), followed by notification of the incident to stakeholders. |

| Containment | In the containment phase, the goal is to take steps to limit the scope and magnitude of the incident. This helps to prevent the breach from spreading and causing further damage. The principal aim of this phase is to secure data while limiting the immediate impact on customers and business partners. If possible, disconnect affected devices from the network and the internet. Any strategy you implement should depend on whether the attack is ongoing or complete. |

| Eradication & recovery | Once the incident is contained, the cause can be removed, and the system returned to a secure state. Eradication is the complete removal of the problem. In this phase, all causes of the problem are removed, and devices are completely malware-free. Recovery includes a full or partial reconstruction to bring the system to full function. Recovery should also include evaluating system security and hardening network resources. As demonstrated by the arrow from Eradication & Recovery to Detection & Analysis, the response process may have to iterate through multiple phases of detection, containment, and eradication to effect a complete resolution. |

| Post-incident activity | The post-incident activity and feedback phase, also referred to as the lessons learned phase includes:

|

Response Methods

A security incident is an event or series of events resulting from a security policy violation that adversely affects a company's ability to proceed with business. Security incidents can include any of the following:

- Employee errors

- Unauthorized acts by employees

- Insider attacks

- External intrusion attempts

- Virus and harmful code attacks

- Disclosure of proprietary information

Incident response is the actions taken to deal with a security incident during and after the incident. Prior planning helps people know what to do when a security incident occurs. All company leaders and technical employees should be familiar with the incident response plan. At least one member in every department should be trained to recognize abnormal activities, suspicious behavior, unauthorized activity, and irregular patterns in employee conduct. Appropriate actions for an employee to take when discovering an incident are:

- Recognize and declare the event.

- Preserve any evidence that may be used in an investigation.

- Contact the appropriate personnel.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

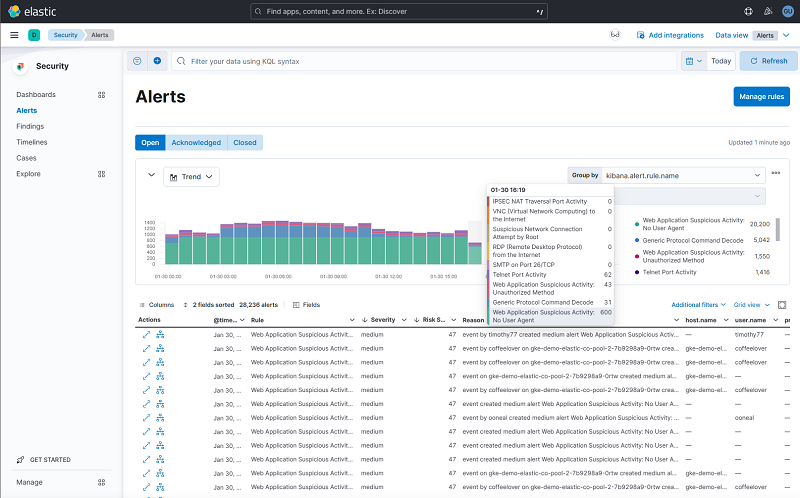

Identifying indicators of compromise (IoCs) is the first step in incident response, and what happens next is highly dependent upon what tools are in place. An indicator of compromise represents a clue (or sometimes a clear notice!) that the environment has been breached in some way. By definition, monitoring for indicators of compromise is reactive and, therefore, most effective when IoCs can be detected as early as possible. The potential sources of information used to locate IoCs are vast, but heavy emphasis is placed on log data and end-user reporting of suspicious activities.

SIEM tools play a critical role in monitoring for IoCs. They can collect and process log information across many sources and reconstitute the data into actionable outputs. In high-volume/high-capacity environments, the amount of log data generated by infrastructure and systems is overwhelmingly vast. SIEM platforms help funnel this mountain of data into outputs that are more easily understood by analysts. They also enable outputs to be automatically pre-analyzed by SOAR tools.

High-priority alerts generated by any security tool warrant immediate and close inspection. For example, alerts of vulnerabilities with a severity rating of 10/10, labeled as severe, or with high-priority ratings, such as when suricata rules match with a priority value of 1, should be investigated first. Alerts should not be processed in the order in which they were received.

The following is a summary list of some common indicators of compromise:

- Atypical or unusual inbound and outbound network traffic

- Administrator, root, or other highly privileged accounts being used in any unexpected way

- Any account activity representing access or actions which should not be possible using the identified account

- A high volume of invalid password entries

- Unexpected increases in traffic volumes, especially database or DNS traffic

- High volumes of requests to access a single file

- Suspicious changes to the Windows registry or any unusual change to system files

- Atypical requests to Domain Name Servers (DNS) or strange domain name resolution requests

- Any unauthorized changes to system settings and/or mobile device profiles

- Large quantities of compressed files stored in unexpected locations

- Traffic originating from countries where the organization does not operate or have any business dealings

- Any strange or unknown applications running on a system

- Any unknown or suspicious scheduled tasks

- Strange or unknown processes running on a system

- Strange or unknown services installed on a system

- Alerts from IDS/IPS, firewalls, endpoint protection, or any other security tools

- Any unexpected instances of encrypted files

- Any activity on a system that indicates remote access/control that is not expected

Preparing for Post-incident Activity Phases

video

Preparing for Post Incident 00:00-08:30 James Stanger: You know, when it comes to incident response, you've gotta make sure you have the right kind of plan. To talk to us more about that plan, we've brought in Mitre's Jamie Williams. Jamie, how you doing?

Jamie Williams: Pretty good. How are you?

James Stanger: Doing great. Jamie is the Principal Adversary Emulation Engineer at Mitre and you know quite a lot about incident response. Let's start talking a bit about what it means to actually create that plan. What are some of the tools and things, for example, playbooks that you use to make sure you actually have a plan?

Jamie Williams: Yeah, so incident response is one of those really interesting topics because it sounds like, you know, it sounds like a really straight forward process, but really in reality, it's stressful. You know, alarms are going off, you know, lights are flashing, you know, a lot of people are yelling, people are concerned and scared.

So you really need to like, exactly as you said, have a plan. Make sure you're not, you know, you're not just doing improv. You don't know what you're doing and you're panicking, but really like you said, you have those playbooks. We have step by step, almost thinking of it like, a recipe; like you're baking a cake. What's step one, what's step two?

Even if you're not gonna follow that verbatim, making sure you kind of have that checklist to make sure, you know, you're making, you know, you're proceeding through all those steps, but also just that confidence of looking back and saying, you know, you're giving yourself that benefit of you know, I'm doing the right thing right now.

And again, I think, regarding, it's a little bit of a cliche, but you know, everyone always says, like, planning's the most important step. For incident response, it really is because it's just, you don't, you know, there's so many things going on in terms of making sure you have the right data, the right people are involved, you're communicating with the right stakeholders.

You know, the conclusions are going to the right places. All of that just isn't going to happen on its own, so whether you're, you know, documenting that or you know, tabletopping it in advance, just making sure, you know, when that alarm goes off or when that alert fires into the dashboard, you know instinctively, you know, where to go, what to start doing. I think that's really what we're trying to capture versus you know, everyone throwing their hands up and just starting doing whatever feels right and eventually just leading to a really bad place.

James Stanger: But like you suggested, improv is probably a bad thing to be doing 100% of the time. Now what does a playbook look like, for example, and how do you create one? Is it a spreadsheet? Is it a collection of documents, things like that?

Jamie Williams: I like to think of 'em, like, it could be a spreadsheet. I like to, like I said before, think of it more like a recipe of like, what needs to happen, where are the ingredients? Whether it's data, whether it's certain resources, particular positions. Who needs to be involved, what are they doing? And really, how do we proceed from, you know, identification of an incident to that eradication and recovery?

So what do those steps look like? And exactly as you said, it might take many different forms, whether it's, you know, a password being leaked or a system going down or you know, even more particular threats like Ransomware or we're having [data exfil]. So it can take a lot of different forms, but really organizations can start, you know, documenting and billing those out, especially your business is gonna be very different.

The way you handle this, who's in involved? What tools and what resources you have are not only gonna be different for you, but also are gonna evolve and grow over time. So not only, you know, as you know, you're buying new tools and you're hiring new staff, staff's leaving, you're automating things, but also, you know, as you're going through that process.

You know, thinking about like, the recipe example, you know, you might have a really simple recipe for baking a cake and maybe you use it and you realize, okay, there's a fourth step or there's a fifth step or maybe the oven needs to be a little bit hotter.

So treating it like a living document where as you're using it, as you're table-topping it, as more people see it, documenting more, adding more context and really kinda using it almost like a knowledge management system. Again to your point where, you know, in case of emergency, break glass, you basically have these cheat sheets for exactly what to do to make sure you're kinda checking all those boxes and getting back to a good place.

James Stanger: Because this is really how to maintain business continuity, protecting the most important elements, the crown jewels of the organization, right?

Jamie Williams: Exactly. Security is an enabler for the business. So again, you know, an imperfect incident response plan would be just to turn everything off and stop production. I mean, that might, unfortunately it might have to come to that sometimes, but ideally you kinda have that, you know, kind of exactly as you said, lens of, how do I get things back, not only to operational state, but safe? But also, you know, understanding how did we get here and how do I prevent this from happening again? And how can I use both that, you know, retroactive playing process as well as maybe insight some others to maybe bolster that?

James Stanger: And so getting the word out about the playbook as it were, you use things like tabletop exercises and live fire training and things like that. Tell me a bit about tabletop exercises.

Jamie Williams: Yeah, so it might seem silly, but it can be as simple as sitting down with the right stakeholders and saying, you know, you have a machine that starts floating off to a known bad IP. What do you do? Who's involved? What's step one, what's step two? 'Cause again, like you said, it might seem like a silly question.

You know, we have Ransomware. We have had Ransomware alert on one host, where our domain controller goes down. It might seem like a really simple and silly question, but you know, as you start to really think through, well, what's step one, what's more important? And especially, all the stakeholders that might be at that table, there might be a lotta different opinions and maybe some, you know, disagreements that need to be hashed out before.

Exactly like you said, last thing you want is the situation to be real and then you're dealing with those disagreements and kinda struggling to make decisions versus already kinda thinking that through and knowing exactly, okay, the IR team goes first, the forensic team goes second. You know, the mediation team goes third, then communication and admins.

Whatever your process is, making sure it's something that not only is documented, but is mutually agreed upon, 'cause the last thing you want is ten chefs in the kitchen arguing over who uses the oven first.

James Stanger: That's great. And then, from tabletop, you actually go to actually let's do an actual drill. You know, a visible drill as it were, you know, throughout the entire organization to see how well that tabletop exercise worked, right?

Jamie Williams: Exactly, it's like a fire drill. Like, everyone just says, like, getting out of the building seems easy, but then you don't know the doors you might cross or the hallways you might have to walk through, the different staircases. So exactly like you said, actually making sure that you know what it looks like. You know, it's not gonna be a surprise to you when this big alert goes on the dashboard, but also it's a really good opportunity for process refinement and tuning, in terms of, well, the tabletop, things might've seemed ideal.

You might've thought best case scenario, but in reality, when you actually kinda go through those motions, it might not be as clear. There might be a little bit more nuance and a lot more, you know, maybe the alert isn't as clear as it should've been or shutting down that system isn't as easy as you thought it would be. So, just making sure you kind of, you know, work out all those kind of, you know, that connective tissue so that again, ideally, when an incident happens, this isn't the first time you've done all those steps in terms of baking that cake.

James Stanger: Okay, so the cake has been baked, right. It's even been served, as it were. You know, we're after the incident, as it were. What kind of post incident activity is there? For example, a root cause analysis, things like that. How does that work?

Jamie Williams: Root cause analysis is a huge one 'cause the first thing you wanna understand is why? Why this happened, but most importantly, how do we stop this from happening again? But I think one of the other big ones that is under-appreciated is just taking a step back and understanding the bigger picture, but also communicating that and sharing that with others.

You know, was anyone else impacted by this? Should they be informed about this? But also, has anyone else lived through this? Has anyone baked a cake and maybe it wasn't as soft as we wanted? Maybe the cream just wasn't right. Looking at, is there lessons learned that we can take from other folks who lived this exact same experience? Maybe they had the same malware, they had these same alerts.

Is there things that they noticed that they did that we can learn from and maybe adopt into our recipe, but also things that we can share with them and really build this out as a community? 'Cause really, at the end of the day, it's us versus these adversaries, so the more that we can kinda share these lessons learned and kinda pass these nuggets back and forth, the better cakes we're gonna bake all together.

James Stanger: You know, you're making me hungry to learn more about security and also to go out and get a nice cake, so Brian, thank you so much, it's been fantastic to learn about what it means to do some proactive, some preparation for that playbook and also post incident recovery in regards to an incident. Thank you so much, man.

Jamie Williams: Thanks for having me.

9.2.6 Incident Response Preparation

Click one of the buttons to take you to that part of the video.

Incident Response Preparation 00:00-00:22 An organization should be able to respond to security incidents calmly and consistently. This is almost impossible without plenty of preparation. The purpose of an incident response plan is to adequately prepare for security incidents. It is proactive rather than reactive.

Policies and Procedures 00:22-01:03 An incident response plan provides the baseline—the policies and procedures—an organization should follow in the event of a security incident.

A policy should outline roles and levels of authority, define security incidents, specify performance measures, and include necessary contact and report forms. Be sure not to include specific technologies in your policies, as these are subject to change frequently. You don't need to explain your specific response procedures in your policies; that's part of your procedures.

A procedure should include a detailed technical operational plan and play-by-play response strategies, often documented in a playbook.

Documentation 01:03-01:07 Documentation is a critical part of any incident response plan.

Plan Documentation 01:07-02:23 Plan documentation should be easy to read and should include concise guidelines that can be easily referred to as needed during an incident response event. Resources, policies, and procedures should be well-documented and should be easily accessible to executives and staff members. The only way to ensure adequate coordination is to maintain excellent records.

There are a few documents that should be part of all incident response plans. First, an incident checklist that provides an overview of activities that should be completed any time there is an incident. Incident response can be fast-paced and stressful, so the checklist helps make sure important steps aren't missed. An escalation list includes the contact information for the person or persons responsible for responding to an incident. The contact person may differ depending on the type and severity of the incident. This list should be printed out and easily accessible. An incident form is used to track critical details about an incident. It should include the date and time of an incident. It should specify who or what detected the incident and where. And it should include a description of the incident and a detailed explanation of the response.

Data Criticality and Prioritization 02:23-04:05 Waiting to take stock of what you have until after an attack is a choice your future self will regret. Many organizations have found themselves in the uncomfortable situation of trying to figure out what information is missing or compromised after an attack. Although it's time-consuming, it's definitely better to track your data before you lose it. The data criticality and prioritization process provides your organization with information and documentation on what types of information – public and private – is processed, where it's processed, and who has access to this information.

Let's look at several types of data that should be secured and tracked closely. First is personal identifiable information. This could include a person's name, date of birth, address, and social security number – specific things that can be used to differentiate one person from another. Next is personal health information such as insurance information, medical records, and lab results. Sensitive personal information includes data that is private and could result in a potential bias for hiring or other decision-making purposes. This could include religious or political beliefs or sexual orientation, and its collection requires consent. Individual financial information includes banking accounts and credit card information. Corporate information includes data from all aspects of a business, like customer information, contracts, legal records, and product development. Information that is proprietary to an organization is often subject to intellectual property rights and could include details about copyrights, patents, or trademarks.

Communication Plan 04:05-04:11 Incident response involves communication and coordination between multiple internal and external parties.

Internal Communication 04:11-05:29 As part of your planning process, you should establish a response team and appoint someone as its point of contact. System administrators know their network and their equipment. They're the best equipped to provide information, detect the cause of an incident, and help with recovery efforts. Most incidents should be reported to an immediate supervisor or manager. Depending on the nature of the incident, you may also need to escalate the matter to members of your senior management team. Your management team may decide to bring additional stakeholders into the loop. For example, any time there's room for compliance issues, regulatory violations, or potential lawsuits, a legal team should be involved. Additionally, If an incident could result in negative publicity, your public relations representative will need to know. They'll handle the release of information through reputable sources and agencies. Any questions from the outside should be fielded through public relations.

Secure communication methods such as email, messaging, and phone calls should be established during the incident response planning phase. Because of the sensitive nature of incident response, you don't want to risk employees using unsecured and unapproved methods of communication while sharing information about an incident.

External Reporting Requirements 05:29-07:33 Depending on the type of breach you experience, various laws and regulations may require you to report security incidents.

Law enforcement may need to be contacted or may contact you when an incident involves criminal activity. Organizations should seek legal counsel before responding to requests from law enforcement agencies. Vendors may also prove to be helpful during an incident. Because their technologies are being used within the organization, they may be able to help with recovery, security patches, guidance, or troubleshooting. Contact information for all relevant vendors should be maintained. If your organization falls under a regulatory body, you may be required to report security incidents. Your incident response plan should include what type of incidents should be reported, who you should report to, and when you need to make the reports. Many organizations assign a primary contact person to handle interactions with regulatory bodies. This is important for smooth and consistent communication.

Let's look at a few common incident types that may require outside reporting. Data exfiltration occurs when an attacker removes or transfers data from your system to another. In some instances, data exfiltration can be hard to prove because the information isn't missing, it's just been copied. Because of this, a suspected breach should be treated as seriously as a known breach.

Insider data exfiltration is the same as data exfiltration except that it's performed by an employee or someone with authorized access to the system. Some attacks are designed to target the availability or integrity of a system or network. Even if there isn't a suspected data breach, you may still need to report these types of incidents.

An accidental data breach usually happens because of an employee error or a system misconfiguration. If the breach results in data being shared with unauthorized persons, the incident will probably need to be reported. If a device is lost or stolen, it may also need to be reported.

Training and Testing 07:33-08:00 One of the most important parts of incident response preparation is making sure that your systems and employee know what to do. Penetration testing can be done to ensure that your systems are ready, and training can be done to ensure that your employees are ready. The failure or success of a team to detect, eradicate, and recover from a security incident can have a serious impact on an organization's time, finances, and reputation.

Summary 08:00-08:19 That's it for this lesson. In this lesson, we discussed incident response preparation. We reviewed the importance of policies and procedures, documentation, a communication plan, training, and testing.

9.2.7 Incident Response Plan Components Facts

The purpose of an incident response plan is to adequately prepare for security incidents. It helps an organization respond to security incidents calmly and consistently. An incident response plan provides the baseline for an organization’s incident response. The plan outlines policies and procedures that should be followed in the event of a security incident. Organizations should tailor an incident response plan to their unique needs and circumstances, but they all have common components.

This lesson covers the following topics:

- Incident response policies

- Incident response procedures

- Incident response tools and resources

- Creation of response plans

- Testing of response plans

Incident Response Policies

Incident response policies are statements of the organization's expectations and procedures for responding to security incidents. These policies typically describe which incident types must be reported and should provide detailed descriptions of the steps to be taken in the event of an incident, the roles and responsibilities of those involved, and the communication protocols to be followed. The organization should also develop a timeline for responding to incidents, including the timeline for reporting and responding to them. It should also include a timeline for determining the cause of the incident, the recovery process, and the steps to prevent similar incidents in the future.

A policy should include:

- Definition of what constitutes a security incident.

- Outline roles and levels of authority.

- Include necessary contact and report forms.

- Specify performance measures.

A policy should not contain:

- A list of specific technologies. These are subject to change.

- A detailed technical operational plan.

- Documentation of response procedures.

- Specific forensic or evidence-gathering methods.

Incident Response Procedures

Incident response procedures describe organizations' actions during incident response. These procedures include the protocols for how different parts of the organization work together to mitigate incidents and the procedures for how individuals should respond. They provide a detailed technical operational plan with play-by-play response strategies.

| Scenario | Description |

|---|---|

| Ransomware | A ransomware playbook describes the people, processes, and tools to be employed during such an event. It should include considerations for determining which systems were impacted, methods by which impacted systems can be immediately isolated, and identification and engagement with the people needed in the response. Ransomware responses should include disconnecting and isolating networks as quickly as possible. It is preferable to disconnect systems as opposed to powering them off to maintain forensic integrity and potentially extract cryptographic keys from system memory which can be used for remediation. |

| Data exfiltration | Used in response to an adversary that has targeted, copied, and transferred sensitive data. Data exfiltration can use many avenues, from the literal movement of data files to less obvious examples, such as is accomplished via an SQL injection attack. Data exfiltration playbooks include the specific and necessary tasks needed in response to data exfiltration, including notification requirements and system and network forensic analysis to determine exactly what was accessed. Sometimes analysis can reveal the locations where data was copied, which can help in response decisions. Deleting copies of data on an adversary's system is considered a hack-back action. It may only offer limited mitigation depending on whether additional copies of the data exist. |

| Social e ngineering | A social engineering playbook often involves responses in relation to an identified phishing email. As soon as a suspicious email is identified, an official notice should be broadcast to advise of the attack and encourage others who may have responded to the email to step forward. In parallel, the phishing email should be searched for within the entire email system to identify any other instances, and any elements within the email (such as dynamic body content, hyperlinks, and attachments) should be analyzed within a sandbox to fully understand what the message is designed to do. Information extracted from sandbox analysis can be used to feed security infrastructure, such as blocking access to IP addresses and URLs, as well as crafting updated detection rules in IDS, AV, etc. At a bare minimum, impacted individuals should have their passwords reset and possibly replace their desktop systems. |

Incident Response Tools and Resources

Incident response tools and resources describe the wide range of specialized tools needed during an incident response. Incident response activities require everything from simple phone numbers of support teams, to software to manage the incident response process, to specialized tools designed to help better understand what is happening. Organizations often use various types of incident response planning software to help identify potential threats and incidents, conduct risk analyses, and create response plans. The software can also be used for testing and exercising incident response plans and for maintaining those plans over time. Some common tools associated with incident response include the following:

| Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) | Collect and analyze log data and provide a single viewpoint for logs collected from many sources. It helps to locate specific events or event sequences. |

| Intrusion detection systems (IDS) | Provides alerts when suspicious events occur based on established or custom-crafted signatures developed to locate events specific to an incident. |

| Vulnerability scanners | Identify the presence of a vulnerability, especially one under active attack, and can also provide assurance that a previously identified vulnerability has been remediated. |

| NetFlow Analyzers | Provide high-level visibility into the volumes of traffic and protocols in use in the environment. |

| Infrastructure monitoring | Tools used to monitor availability, latency, capacity, and other elements. Typically associated with engineering teams and used to ensure the health and uptime of infrastructure components such as servers, storage environments, and network equipment. |

| Proxies and gateways | Firewalls, routers, and forward proxies (internet traffic) provide valuable insight into traffic leaving and entering the network. These can be used to alert specific traffic or analyzed to locate historical events. |

Identification of Potential Threats and Incidents - Threat modeling, risk analysis, and other threat identification activities can help organizations identify potential threats and incidents that could impact the organization. Incident types include cyberattacks, natural disasters, and other events that could disrupt normal operations. Threat modeling tools can help organizations create threat models and analyze identified threats and incidents comprehensively by creating detailed diagrams that support team collaboration.

Assessment of Potential Impacts - Organizations use risk analysis and impact assessments to measure the scope of identified incidents in the organization. Risk analysis tools include guided questionnaires and templates designed to help individuals collect information and produce detailed reports on their findings.

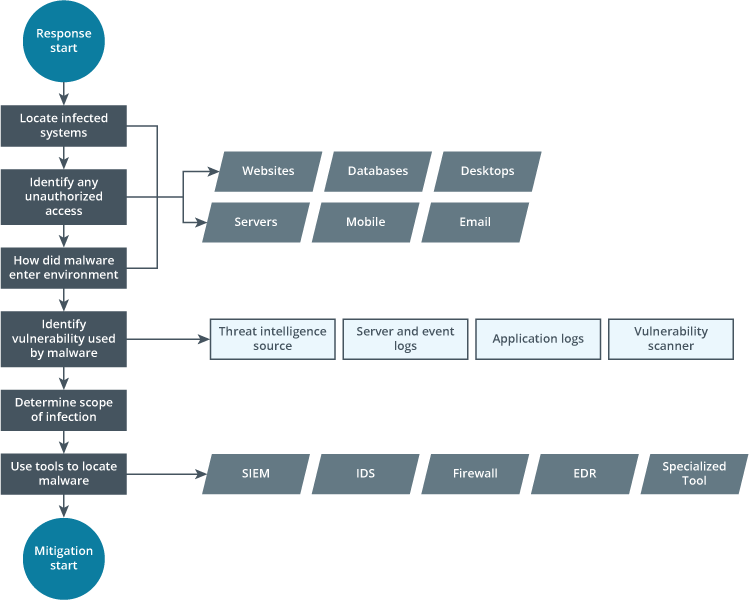

Creation of Response Plans

Organizations create response plans to handle incidents based on the threats and incidents identified during risk assessment activities. Response plans should leave little to the imagination. They should be concise and direct, with detailed steps and clear expectations. Flowcharts are a popular tool in the incident response arsenal. An example flowchart for responding to a malware infection event may be similar to this one:

A flowchart for responding to a malware infection event.

The steps are as follows:

- Locate the infected systems or resources, such as websites, databases, desktops, servers, mobile, and email.

- Identify any unauthorized access to those resources.

- How did malware enter the environment via those resources?

- Identify the vulnerability used by malware via threat intelligence source, server and event logs, application logs, or a vulnerability scanner.

- Determine the scope of infection.

- Use tools to locate malware, such as SIEM, IDS, firewall, EDR, and other specialized tools.

Testing of Response Plans

Organizations test response procedures to ensure that personnel know how to respond to specific incidents and that the responses are effective. It is critical that all participants are properly trained as well as participate in testing. Some incident response testing activities include the following:

| Activity | Description |

|---|---|

| Tabletop exercises | Tabletop exercises are a type of incident response planning activity that does not involve a mock incident or full incident simulation. During tabletop exercises, organizations bring together the personnel who would respond to an incident, often in a simulated setting, to test the effectiveness of their communication and response plans. |

| Mock incidents | Scenario-based simulations that organizations create to test how the incident response plan works in practice. Mock incidents can include simulations of different types of incidents that might occur, such as earthquakes or malicious cyberattacks. |

| Full incident simulations | Mock incidents that include the full set of people and organizations involved in responding to an incident to test the entire response process, including communication protocols and the effectiveness of the different response teams. |

9.2.8 Triage and Incident Response Facts

Incident response involves more than software and devices. The people and organizations that depend on technology need to know what is happening in a language that is meaningful to their point of view.

This lesson covers the following topics:

- Triage event

- Playbooks

- Documentation

Triage Event

Properly determining the scope of a security incident occurs during triage. Triage work is dependent upon the skills and knowledge of the individuals performing the work. It includes careful curation of the data and tools useful in locating any indicators of compromise. Individuals performing this work should have specialized training and experience in a live system, digital forensics, and memory and malware analysis.

Triage work is often performed on endpoints, within executable and binary files, and using enterprise security infrastructure tools such as SIEM. Ultimately, triage work is focused on determining a timeline of what, where, how, and when events occurred.

Having clearly defined processes, thresholds, and notification procedures in place as part of a security incident pre-escalation plan is imperative to rapid response. The lack of a clear plan regarding what constitutes an urgent situation or knowledge of what to do when a situation is identified will result in problems being stuck in ticket queues or bogged down in bureaucracy. At the same time, an adversary furthers the impacts of their attack.

Playbooks

Incident response playbooks are an invaluable tool for organizations to quickly and efficiently respond to security incidents. With an incident response playbook, organizations define the steps they need to take to respond to a security incident, such as the specific roles, processes, and procedures that security staff must follow. Incident response playbooks also guide communication with stakeholders and the public, as well as guide how to gather evidence and determine the incident's root cause.

Oftentimes the playbook is just that—a physical book used by a security analyst in response to an incident. It is a checklist of actions to perform to detect and respond to a specific type of incident. Using a physical book ensures its availability during a wide-scale incident. In a highly secure environment, it also ensures the IR capabilities are not digitally exfiltrated by attackers.

The most effective incident response playbooks are tailored to an organization's specific security needs and provide detailed guidance on responding to various security incidents. For example, a playbook may contain detailed instructions on responding to a ransomware attack or a data breach. Additionally, the playbook should include guidance on the necessary steps to contain the incident, such as isolating affected systems and measures to ensure the incident is fully resolved.

When creating an incident response playbook, organizations should ensure they have the right level of detail and that all necessary stakeholders are involved, including security teams, IT staff, legal teams, and other personnel who may be involved in responding to the incident. Organizations should update the incident response playbook as new threats and technologies emerge.

Documentation

Documentation is a critical part of any incident response plan. Plan documentation should:

- Be easy to read.

- Include concise guidelines.

- Document resources, policies, and procedures.

- Be easily accessible by executives and staff members.

- Be easy to refer to during an incident response event.

Maintaining excellent records will help ensure coordination, sharing of information, and the best possible incident response.

The following table provides a list of commonly maintained incident response documents:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Incident checklist | An incident checklist provides an overview of activities that should be completed anytime an incident occurs. Incident response can be fast-paced and stressful. You can use the checklist to verify that important steps are taken. |

| Incident form | An incident form is used to track critical details about an incident. It should include:

|

| Escalation list | Key points about an escalation list include:

|

The data criticality and prioritization process:

- Identifies the types of information (public and private) processed.

- Specifies where the information is processed.

- Identifies who has authorized access to the information.

The following table identifies several types of data that should be secured and tracked closely.

| Data Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Personal identifiable information (PII) | PII includes data specific to a person’s identity. This can include:

|

| Personal health information (PHI) | PHI includes data that is specific to an individual's private health information. This can include:

|

| Sensitive personal information (SPI) | SPI includes data that is private and can result in a potential bias for hiring or other decision-making purposes. This type of information requires consent to be gathered. It should not be collected or used without a specific purpose. SPI can include:

|

| Individual financial information | Financial information includes:

|

| Intellectual property | Intellectual property information includes proprietary data that has been created for and is owned by the organization. This usually includes:

|

| Corporate information | Corporate information includes all aspects of a business and can include:

|

9.2.9 Stakeholder Communication Facts

Incidence response requires communication with multiple people, both internal and external to the organization. Because of the sensitivity of any incident, it is important to know what reports need to be created and to whom the reports need to be given. The type of breach will dictate who should be informed and how long you have to inform them.

This lesson covers the following topics:

- Incident declaration and escalation

- Communication plan

- Stakeholder management

Incident Declaration and Escalation

Incident declaration and escalation are critical components of incident response. It is the process of recognizing and officially declaring an event as an incident, as well as the process of escalating the incident to the appropriate personnel.

The first step in incident declaration and escalation is identifying an incident, such as recognizing a potential security event and confirming that it constitutes a verified security incident. The category of "incident" is broad and includes everything from full-scale data breaches to something as simple as a protected document printed inappropriately. After identifying and confirming a security incident, the next step is the official declaration of the event as an incident. Incident declaration includes documenting the incident details, including its severity, and notifying the appropriate personnel via escalation procedures.

Depending on the type of incident, there may be multiple escalation levels. For instance, in a data breach, the incident may need to be escalated to executive management. Alternatively, if the incident is an attempted intrusion, it may need to be escalated to IT staff or a security operations center. An incident must be declared or escalated to the appropriate personnel for it to be properly addressed. Unaddressed incidents will likely result in significant future issues, jeopardizing the organization's security.

Communication Plan

A secure method of communication between the IR team members is essential for successfully managing incidents. The team may require "out-of-band" or "off-band" channels that attackers cannot intercept. In a major intrusion incident, using corporate email or VoIP runs the risk that the adversary can intercept communications. One obvious method is via smartphones, but ideally, the messaging system should support end-to-end encryption, digital signatures, and encryption keys supplied by a system independent of the identity and access management systems used by the attacked environment.

Once a security incident has occurred, communication is key to carrying out the plans your organization has developed for such cases. Having a set process for escalating communication will facilitate the knowledge and teamwork needed to resolve the incident and bring the organization's operations back to normal. The IR team should have a single point of contact to handle requests and questions from stakeholders outside the incident response team, including both executives within the company and contacts external to the company.

Steps must be taken to prevent the inadvertent release of information beyond the team authorized to handle the incident. Status and event details should be circulated on a need-to-know basis and only to trusted parties identified on a call list. Trusted parties might include both internal and external stakeholders. It may not be appropriate for all members of the IR team to be informed about all incident details.

It is imperative that adversaries not be alerted to detection and remediation measures about to be taken against them. It is harmful to publicize an incident in the press or through social media outside of planned communications. Ensure that parties with privileged information do not release it to untrusted parties, whether intentionally or inadvertently.

Stakeholder Management

Stakeholders describe any individual, group, or organization that can affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by a decision, activity, or outcome relating to an incident. Identifying stakeholders is the first step toward successful stakeholder management, as they are not always obvious. It is vital to identify, analyze, and prioritize stakeholders' perspectives, informational needs, expectations, and interests. These will dictate the communication methods and the content of the message.

After identifying stakeholders, it is essential to develop effective communication strategies to address their needs and interests. Building strong relationships with stakeholders is crucial and is accomplished by providing accurate and timely information, listening to feedback, and responding to requests. Effective communication helps to manage expectations, resolve conflicts, and foster collaboration.

Regular communication with stakeholders should be part of the incident response process to ensure they know the status of the incident. The method of communication depends upon the stakeholder and could include face-to-face meetings, emails, text/chat messages, telephone calls, or video conferencing. The sensitive nature of the incident response requires that employees use secure, approved methods of communication. Incidents impact stakeholders, and their areas of responsibility may be shaped by their knowledge of the incident. Keeping stakeholders informed helps them manage their responsibilities (affected by the incident). It often reveals information the responders may not have previously known, such as alternative processes, business relationships, impacts, and consequences.

Leveraging the communication plan, incident responders must coordinate between internal departments and external agencies, such as law enforcement and regulators. The following are some examples of internal and external stakeholders that will likely be relevant to any incident response.

The following table provides a list of internal stakeholders:

| Stakeholder | Description |

|---|---|

| Senior management | Depending on the nature of an incident, you may need to escalate incidents and response attempts to members of your senior management team. |

| Legal department | Depending on the nature of a security incident, you may need to involve an attorney or a legal team. Involve the legal team when there are:

|

| Public relations | The public relations team manages external communications to avoid or reduce negative publicity. They develop press releases, participate in media interviews, communicate with the organization's customers or constituents, and perform many other tasks. Public relations specialists are skilled at delivering "just enough" information and must often balance legal, ethical, and public interests. Any questions from the outside should be fielded through public relations. |

| Human resources | Human resources (HR) should be involved in incident response training programs. Involve HR if a security incident involves an employee, employee data, employee contracts, etc. Insider threats should be reported and mediated through the HR department to mitigate potential issues. |

| Response team | As a part of the planning process, establish the response team and delegate a leader/point person. |

| System administrators | System administrators know the network and the equipment. They will be best equipped to provide information, detect the cause of an incident, and help with recovery efforts. |

| Employees/other departments | Depending on the type of incident, notifications may need to be sent to other departments or individual employees, especially if employment records were compromised. Issues caused by the incident may also affect business processes requiring notification of employees in operations, finance, manufacturing, and more. |

The following table provides a list of external entities:

| Entity | Description |

|---|---|

| Law enforcement | Law enforcement may need to be involved when an incident involves criminal activity. Organizations should seek legal counsel before responding to requests from law enforcement agencies. |

| Vendors and suppliers | Vendors may prove to be helpful during an incident. Because their technologies are being used within the organization, they may be able to help with recovery, security patches, guidance, and troubleshooting. Contact information for vendors should be maintained. |

| Regulatory bodies | If your organization falls under a regulatory body, you may be required to report certain security incidents. Your incident response plan should include:

Note that most organizations assign a primary contact person to handle interactions with regulatory bodies. This is important for smooth and consistent communication. |

| Customers/general public | Depending on regulatory requirements, incidents may need to be shared with customers or the general public. |

| Organizations | Organizations within similar industries may have useful information if they have been recently targeted by similar attacks. Also, they may benefit from your experience. |

The following video discusses the importance of incident response reporting and communication.

Video

Click one of the buttons to take you to that part of the video.

Executing Incident Response 00:00-06:38 James Stanger: Communication during an incident is so important, the level, the maturity of it, and to tell us more about how to have really good communication during an incident, we've brought in Jamie Williams. Jamie, how are you doing?

Jamie Williams: Great. How are you?

James Stanger: Doing great. Doing great. Jamie works for Mitre, he's the Principal Adversary Emulation Engineer at Mitre, which is a fantastic title. Jamie, let's talk about what it means to kinda work with all the different stake holders, and have a really good incident response kind of reporting situation. Tell us what it means to go about it the right way.

Jamie Williams: So, during an incident, obviously, you know, it's a panic. You know, if something bad's happened, we're trying to assess the situation, not only are we trying to understand what happened, but like, why did it happen? How did it happen? Where did it happen? When did it happen? But also, I think one of the biggest lessons is understanding that this isn't just a community-- oh wow.

Biggest lessons is understanding this isn't just a computer security problem, you know, we're not just looking at this from a Texan area where, you know, all the techys are on it, they're doing-- fixing things, [LAUGHTER] and we're gonna move on.

There's so many more stake holders in terms of, you know, I mean, affected parties, the business, anyone kind of in that bubble. And again, to your point, the way you communicate there is gonna be different. You know, the way I talk to the engineering staff, or the system owners, it maybe affected data, you know, there's a data breach or something...

James Stanger: Sure.

Jamie Williams: ...those affected parties, that kind of, you know, I'm not saying you're gonna withhold information but, you know, the way you communicate and the data points they might be interested in, are gonna be a little bit different. So it's a really delicate balance of building that core nuclear store...

James Stanger: Yeah.

Jamie Williams: ...documenting and understanding, here's everything we need to know, and then, you know, who's involved, and what do they need to know? What kind of insights do they need, 'cause again, our bigger picture is not to just, you know, point fingers and, you know, cast this as a huge failure, but to understand collectively where are we, where we need to be, and how can everyone help us get back to a good place?

James Stanger: So, as you declare this incident and escalate it, there are those different stake holders, for example, if there's a school involved, there are various stake holders, whether it be management, the people, the principal, the district superintendent, the school teachers, the students, the students parents, right? These are all examples of stake holders, right?

Jamie Williams: Exactly, and that is it. That's the worry in the way you communicate that, is gonna change for every one of those. You know, the principal is gonna need to be armed with things to communicate with. The superintendents gonna have, you know, a bunch of legal stuff to deal with. The students, and the parents, and the teachers, they're all gonna be potentially affected, and so, there's that instilling trust to make sure they understand, you know, we're not gonna hide behind a sugar coated language and say nothing bad happened.

We're gonna be real and tell you exactly what happened, but instill that trust of, you know, we're handling it, here's where we're going, is this okay with you? Is there anything maybe we need to consider? There might be, you know, really good insights that they have in terms of things that, you know, someone's computer security perspective we didn't notice. Maybe additional activity, or other insights that they might have experienced, that can maybe paint that bigger picture.

But, again, it's arming of those stake holders and of those parties with enough knowledge so that we're all collectively moving in the right direction. But also again, to your point, agreeing on that. Where maybe we think we have a good plan, we communicate it out, and we're getting feedback, where maybe there's regulations we weren't aware of. Maybe there is insights and considerations from the teachers that we didn't consider.

So really, again, treating this like an "us" problem that we can all collectively solve, versus let's divide and conquer and, every man for themselves.

James Stanger: You know, once we determine that impact, you know okay, I like to look at it in terms of, not only was there a, what? You know, whatever that incident that was, but the, so what? You know well, here's what the impact, here's the scope, here's what's happening. 'Cause then that does determine how you communicate, 'cause there are legal issues, right, that could be involved, if it's a school, for example. There are certain regulatory requirements out there, for example...

Jamie Williams: Yeah.

James Stanger: ...in this case that you'd have to make sure you follow.

Jamie Williams: Yep. And I love the way you painted that, so what? 'Cause there's, you know, there's immediate impact, in terms of, you know, maybe reporting requirements, regulation, disclosures, but there's also those residual long term impacts where maybe you lost some data, and it isn't immediately obvious where it's gonna go, but a year from now, two years from now, it might kinda come back and maybe we lost credentials, or we lost potential, you know, PPI, or anything like that.

James Stanger: Mm-hm.

Jamie Williams: Making sure, you know, you're not just closing the book too early and saying, you know, the incident's over, but really, you know, kinda forecasting and understanding, you know, we're not necessarily going to solve all these problems, but the more we can defend ourselves and be aware of them and keep everyone kind of in the right, you know, frame of mind, we can deal with these things and start to plan with them, maybe even before they happen.

So again, to your point, it's not necessarily-- we don't wanna treat this like

Whac-A-Mole where, you know, incident happens and we try to shove it back into this little hole as soon as possible. Let's really understand and take the time to carefully and craft-fully handle this so that, again, you know, there's gonna be no surprizes, or at least as few as possible.

James Stanger: Yeah, okay, so it comes down to kinda the level of maturity of your communications, right, how able you are to communicate? Part of that does include some technical terms that you may not use with all those audiences, but you'll have to kinda translate those for all your audiences. I'm talking about, you know, how long it took us to detect it, for example. Or, how long it'll take us to respond property, right? We call that, like, meantime to detect, or meantime to respond, but these are important metrics aren't they that you'll have to filter to various audiences, right?

Jamie Williams: Exactly, and I think the way it's filtered, and the way it's presented is gonna change by the audience. Where, again, thinking back to, what's your goal with communication? You know, if you're talking to the parents, and the students, and the teachers, they might not really care about meantime to respond, there might not...

James Stanger: Yes.

Jamie Williams: ...that term might not mean a lot, whereas you're talking to your IR team, and you could be blue team, and your detection engineers, that's the right audience. But again, you don't want to potentially hide that information too, because it might be relevant, it's just you kinda have to, exactly as you said, maybe re-cast it of, "Hey, you know, an incident happened on Monday, we noticed it on Wednesday," that's a quick and easy way to maybe paint that metric in a little bit more an accessible way...

James Stanger: Yeah.

Jamie Williams: ...but really to that point, kind of still being transparent and helping them understand what happened, and maybe potentially how they were impacted and considerations on their side.

James Stanger: Jamie, thank you so much for you insights about what incident response reporting really means. Sure appreciate it, man.

Jamie Williams: Thanks for having me.

James Stanger: Yeah.

9.2.10 Reporting Requirements Facts

This lesson covers reporting requirements and the necessity of notifying external parties when certain incidents—notably data breaches—occur. It is essential to identify breach types when assessing reporting requirements.

Notification requirements for different types of breaches are specified in legal and regulatory requirements and include a description of the parties to be notified and often include relevant regulatory bodies, law enforcement, private individuals, third-party organizations affected by the breach, and many others. For example, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) mandates reporting requirements using legislation and requires breach notification to affected individuals, the Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services, and, if more than 500 individuals are impacted, to the media ( hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/breach-notification/index.html ).

The requirements also describe timelines for when parties must be notified. For example, under GDPR, the notification must be made within 72 hours after becoming aware of a personal data breach ( csoonline.com/article/3383244/how-to-report-a-data-breach-under-gdpr.html ).