CYB306 Cyber-Physical Vehicle System Security

Chapter 10: Research Challenges and Transatlantic Collaboration on Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems

Objectives

- Introduction

- A context of predictions

- Dynamic and complex systems

- Key research challenges

- Skills for Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems researchers

- Regulatory environments

- Opportunities for collaboration

- Conclusions

1. Introduction

To a large extent, the research challenges for Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems (TCPS) are associated with meeting regulatory and economic requirements (and the interplay between these two considerations).

Although autonomous cars has been the most immediate concern, it is important to note that freight transportation has already incorporated significant levels of autonomous operation, and that shipping and aviation are also domains of significant opportunity and challenge.

The Trans-Atlantic Modelling and Simulation for CPS (TAMS4CPS) Horizon 2020 project (grant agreement no 644821) ran from February 2015 until January 2017; its purpose was to identify collaborative research opportunities between the European Union (EU) and the United States of America in the area of modelling and simulation to support CPS.

This project identified seven key research themes of mutual interest and discussed the collaboration context and opportunities.

2. A context of predictions

There are a great many, diverse predictions for how mobility will develop in the future; all are predicated on the expectation that autonomy is a significant component of future transport systems.

Intel has proposed that by 2050 the ‘Passenger Economy’ will be worth $7 trillion.

This assumes a shift from vehicle ownership to mobility as a service, which is motivated by increased urbanisation and the need to reduce congestion, ever-growing connectedness, a continued blurring of work and personal life and more ad hoc living arrangements in both.

Major factors influencing this change, they believe, will be pollution and safety concerns leading to regulation that makes other travel modalities more expensive (e.g., through tolls and congestion charges).

This implies a significant reduction in the number of cars: 80% - 90% fewer according to The Economist.

However, this view is disputed by other commentators; Toyota, for instance, believes this prediction is premature and does not take account of other circumstances.

On September 2015, the G7 nations and the EU agreed a declaration on automated and connected driving that recognised the need to establish a harmonised regulatory framework and the need for sustained cooperation in the areas of the following:

- coordinating research, promoting international standardisation within an international regulatory framework,

- evolving technical regulations and

- ensuring data protection and cybersecurity.

Development of regulatory frameworks is required for all TCPS and it is likely that this will evolve over many years (a topic to which we return at the end of this chapter).

Research is required to address the formulation of regulation, the tests and metrics for compliance and the development of technologies that will meet the requirements.

3. Dynamic and complex systems

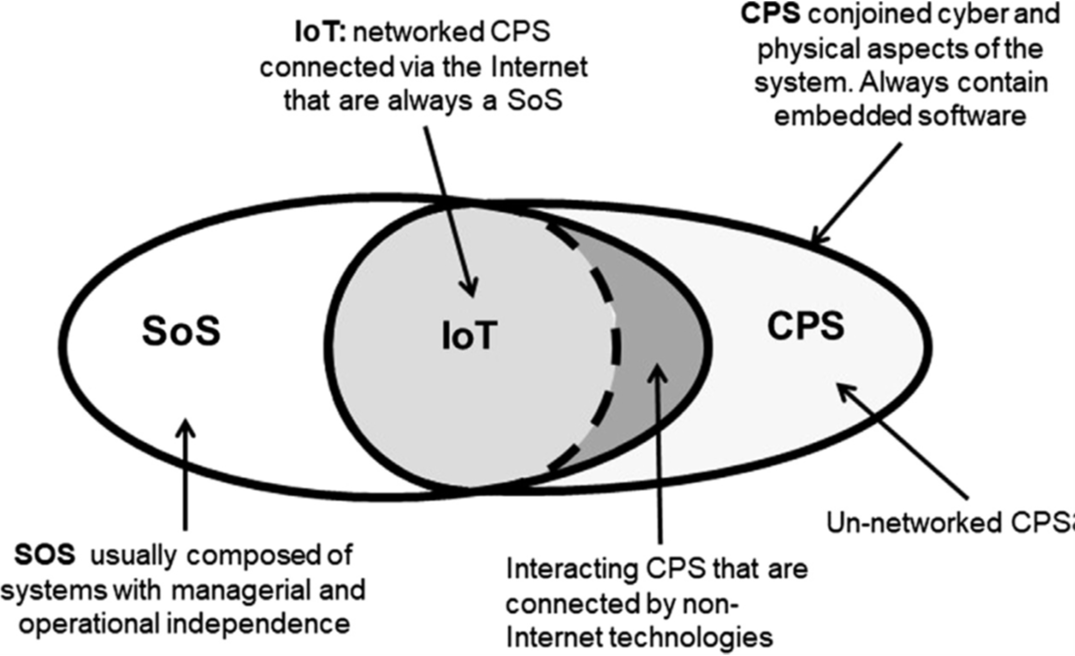

Henshaw has distinguished between CPS, Systems of Systems (SoS) and Internet of Things (IoT); he concludes that the most helpful definition is due to that CPS is ‘the fundamental intellectual problem of conjoining the engineering traditions of the cyber and physical worlds’.

Henshaw distinguishes between four classes of system (see Fig. 10.1):

- An unnetworked CPS: standalone physical system with significant levels of embedded software; typically, this will have appropriate sensors to interact in some way with the external environment in order to complete its operations.

- SoS (independent of cyber components): characterised as a network of systems in which individual component systems have managerial and/or operational independence.

Then combinations of the above two:

- IoT: interacting CPS that are networked (in an SoS sense) via the internet.

- Interacting CPS that are connected by non-Internet technologies (or phenomena).

Figure 10.1 Distinction between systems of systems (SoS), cyber-physical systems (CPS) and the Internet of Things (IoT).

4. Key research challenges

As demonstrated by the foregoing discussion, predictions about future operation of TCPS are many and diverse. However, the discussion helpfully identifies the top-level challenges (or objectives) for TCPS by focussing attention on the parameters that constitute the predictions.

In essence, TCPS must:

- Be acquired and operated in a paradigm that is commercially beneficial and offers better financial and societal value than extant systems

- Reduce the environmental impact of transportation

- Operate safely and, in particular, offer improvements in safety

- Operate within a regulatory framework that protects humans from physical, psychological, and cyber hazards

- Offer individual travellers an improved service over current methods (in terms of cost and/or comfort and/or convenience and/or reliability and/or usable time for work or recreation)

4.1 Security of cyber-physical systems

In 2015, Chrysler issued a voluntary recall on 1.4M vehicles following a cyberattack on a Jeep, that used the entertainment software as an access point to other more critical functions.

This is one example of a risk to TCPS that is likely to grow, according to Loukas, who defines a cyber-physical attack as ‘a security breach in cyberspace that adversely affects physical space’. Loukas draws a distinction between cyber-physical attacks that originate in cyberspace and physical cyberattacks that originate in the physical world but then lead to software or data being compromised.

In fact, for TCPS, both types of attack are of concern and likely to become dominating concerns in the future.

Incorporation of security architectural features into models: one area in which progress may be made to positively influence design in the near term is to identify architectural features related to TCPS security and to develop metrics for secure TCPS.

Security architecture patterns exist for software systems, but these are not yet proven for CPS, which should also incorporate the physical aspects.

The objective of this research would be to incorporate security features as standard into CPS design and integration models, at least for TCPS component systems in the short term.

4.2 Cyber-physical systems testing

There are several reasons for needing to improve testing:

- Verification: verification means testing the system of interest to ensure that it performs as it was designed to perform. Colloquially, this is often expressed as testing that ‘we built the system right’. It is a research challenge in its own right, but conventional approaches, in which a representative (or even the complete) set of conditions are tested to ensure that the outputs of the system are as designed, are not feasible.

- Interoperability: TCPS are predicated on the ability of different CPS to interoperate (i.e., work together), which requires exchanges of information and possibly energy or material. The IoT is clearly concerned with exchange of information, but TCPS may require physical interoperability (e.g., for freight, smart containers may need to be physically interoperable with vehicles). There are many interoperability frameworks; the Net-Centric Operations Industry Consortium (NCOIC) framework considers nine levels clustered in threes as: network transport, information services and people, processes and applications.

- Large-scale test beds for TCPS: TCPS will require the embedding of autonomous systems within the human environment, and this poses numerous safety and security challenges (as discussed above), including long-term consequences for the people involved in the tests. There is a need to understand the likely behaviour of such systems when deployed and also the behaviour of humans when interacting with these systems.

- Evaluation of cross-domain architectures: the development of cross-domain architectures is an important area for research with respect to TCPS, but testing the architectures for assurance purposes also poses a significant challenge. TCPS include many different system owners or operators and it is necessary to share data, especially during a crisis [34]; the CPS architecture may include different software domains but could also be situated in different physical domains.

- Testing for resilience: resilience is an entity’s ability to resist, or achieve timely recovery from, adversity; it is an essential property of TCPS. During operation, a TCPS monitors its environment through a range of sensors and makes decisions to ensure its continued operation; adverse conditions or situations must be detected in order to take appropriate action.

4.3 Human-Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems interaction

Traditionally, humans have been kept safe from robots by keeping them separate, e.g., by putting the robot in a cage; but this is changing across a range of applications.

Whilst much research has focused on the behaviour of the TCPS, attention must also be paid to the behaviour of humans in the presence of TCPS.

- Situation awareness: as early as 1995, Endsley identified situation awareness as a ‘predominant concern in systems operation’ and drew particular attention to the concomitant vulnerabilities due to system complexity and automation. Situation awareness is considered in three levels:

- perception of current situation,

- comprehension of current situation and

- projection of future status.

- Governance: because SoS, by definition, contain systems operated by different entities, some have considered that there are implicit ambiguities with regard to decision-making and liability. For TCPS, there appears to be ambiguity with respect to liability [43], but it is anticipated that the human must retain responsibility. Regulations for road vehicles are formulated around the concept of the driver, but it is suggested that the concept of driver may need to change.

4.4 Verification of Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems

For the software engineering community, formal verification concerns proof of the correctness of mathematical formulations within the software, but for CPS, the physical aspects (which are described differently) must also be verified.

Zheng and Julien reviewed verification approaches currently being undertaken by CPS developers and concluded there is little commonality between various communities about the problem of verification, but recommended that a future research trajectory would integrate simulation tools and fuzzy models into verification approaches.

Combining formal verification and simulation technology: although simulation-based verification is input driven (i.e., an input stimulus is needed in order to simulate the systems output) and formal verification starts from an output (property) and searches for inputs that would lead to failure, combining these approaches is seen as a possible strategy for verifying highly complex systems.

Co-modelling and co-simulation: a corollary of the combination of formal models and simulation is the need for co-simulation, with a wider applicability than verification and especially as a requirement for development of the design process. The nature of CPS means that some models will be discrete event, and some will be continuous time; co-simulation combines these different models (or simulations) by exchanging information between them.

4.4 Verification of Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems

For the software engineering community, formal verification concerns proof of the correctness of mathematical formulations within the software, but for CPS, the physical aspects (which are described differently) must also be verified.

Zheng and Julien reviewed verification approaches currently being undertaken by CPS developers and concluded there is little commonality between various communities about the problem of verification, but recommended that a future research trajectory would integrate simulation tools and fuzzy models into verification approaches.

Combining formal verification and simulation technology: although simulation-based verification is input driven (i.e., an input stimulus is needed in order to simulate the systems output) and formal verification starts from an output (property) and searches for inputs that would lead to failure, combining these approaches is seen as a possible strategy for verifying highly complex systems.

Co-modelling and co-simulation: a corollary of the combination of formal models and simulation is the need for co-simulation, with a wider applicability than verification and especially as a requirement for development of the design process. The nature of CPS means that some models will be discrete event, and some will be continuous time; co-simulation combines these different models (or simulations) by exchanging information between them.

Evolutionary approach to testing and evaluation: a more radical change is to consider continuous testing of the TCPS. Model-based design and testing have been in use for some time; a potential development is to use data-driven models instead so that the systems analyses streaming data to update models and predict future behaviour.

4.5 Big data analytics for control and machine learning

Big data analytics can be developed for TCPS control purposes; indeed analysis of big data is already used to identify trends for commercial or societal purposes and, increasingly, to provide situation awareness for command and control purposes, so that the basis for TCPS control has been established through Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) endeavours (i.e. purely cyber endeavours).

A further benefit of effective data analytics is with regard to machine learning so that the TCPS situation awareness is continually improved (or updated) using data-driven models to describe its environment and even the human behaviours that it may encounter.

There is a massive research effort in data analytics, but the specific methods through which it can benefit TCPS require research.

Sharma and Ivancic have suggested that big data could completely change the models used in CPS and they suggest areas for future research; of particular interest for TCPS is an application such as comparing data from a specific vehicle with many (all) other vehicles, instead of a predefined model, in order to determine interventions such as maintenance.

4.6 Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems operational paradigms

There is a wide range of prediction concerning the value of TCPS in terms of the benefits to operators, customers, the environment, etc., because each prediction makes assumptions about the model of operation of the TCPS (either at local or national level).

For urban transport, Lanctot has suggested a variety of business/operational models tending towards mobility as a service, which actually represents a stark change in human-vehicle relationship, not just in terms of operation but as a mark of social status and financial investment or commitment.

Most models of future transport are motivated by an increasingly urbanised population and although an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimate of urbanisation put the likely proportion at 60% by 2030, that still leaves 40% of the population not included within these models of mobility.

It is reasonable to assume that the motivations for new mobility paradigms are more significant in urban environments, but nevertheless, a much better understanding of the pros and cons of different mobility models is required.

4.7 Summary of research challenges

One of the difficulties in identifying research challenges for TCPS is that there are so many! The massive increase in systems complexity due to autonomy and connectedness offers huge opportunities but also invalidates some traditional engineering approaches.

Similarly, the technology has the potential to be disruptive by enabling new business models for transport.

In terms of the challenges that must be overcome to ensure safe and reliable TCPS, the priorities are creating systems that are cyber secure and the tools and techniques to verify systems for safety, security and performance.

In all cases, the development of suitable models of various kinds and in combination is a priority for research.

5. Skills for Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems researchers

The research challenges described in Section 4 cover a wide range of disciplines in science, engineering and social sciences.

Questions about regulatory aspects of TCPS indicate that law is also a relevant subject (for some institutions, law is within social sciences).

Researchers cannot be specialists in every subject, but Damm and Sztipanovits have suggested that in Europe and the United States, current education in computer science will be inadequate for future CPS engineers and that curricula that include a much wider range of disciplines, especially those relevant to human-CPS interaction, will be needed.

More generally, they state that computer science and engineering courses must incorporate knowledge about the physical world and traditional engineering courses should incorporate more knowledge of the cyber world.

Given that there are almost no systems built, nowadays, that do not include substantial amounts of software, the inclusion of more cyber knowledge within engineering courses should be an imperative.

TCPS researchers must, then, develop a broader knowledge alongside their specialism, but more generally, they should be educated to have a holistic viewpoint in order to appreciate the implications of design decisions on the wider CPS.

6. Regulatory environments

A prerequisite for collaborative research is that there is a shared objective; it is important, therefore, to understand differences between the EU and United States in terms of the likely regulatory environment into which autonomous vehicles are deployed.

In fact, there is currently a lot of similarity in the regulatory environment on either side of the Atlantic, but there are some risks of divergence.

Governments are alert to the need and are active in the development of regulation in the automotive sector.

Currently, it is a common regulation that requires a human driver to be able to take over if necessary, but this will likely become inappropriate in the future and does not affect the research endeavours identified.

Overall, although it is likely that there will be different regulatory requirements between the United Kingdom, EU and United States, they are unlikely to be of a nature to affect the research agenda put forth in this chapter or to have a significant impact on the research carried out in TCPS, with the exception of operational paradigms

7. Opportunities for collaboration

- It had been predetermined that the most prominent opportunities for collaboration were in modelling and simulation for CPS and the following seven research themes were identified:

- CPS test beds

- Inclusion of human factors in modelling and simulation for CPS

- Open framework for model interoperability

- Incorporation of security architectural features into models for CPS

- Combining formal verification and simulation technology

- An evolutionary approach to testing and evaluation of adaptive/resilient CPS

- Big data analytics modelling via machine learning

8. Conclusions

There is a huge amount of research being conducted worldwide into CPS, and TCPS receives significant attention as an underpinning aspect of the development of smart cities.

This review has necessarily considered a very narrow set of references and has been mostly focused on automotive transport, with only a few comments on air and maritime vehicles.

It has considered infrastructure aspects very slightly and ignored space assets entirely, even though they are an essential capability to enable many aspects of TCPS.

There has been much speculation about the operational structure of future mobility; new structures will undoubtedly arise because of CPS and it is by no means certain that universal structures will emerge.

The research challenges identified herein will be relevant to any future structure; however, the specific implementation of research outputs could be very different, depending on the TCPS models adopted.