Cybersecurity System Audits

Chapter 2 – The Audit Process

Objectives

- Key Audit Standards and Frameworks

- Understand the COBIT Controls Framework

- Explore General Computing Controls (GCCs)

- IS Controls and Audit Procedures

- Types of Audits and Samplings

- Audit Methodology

- CAATs

- Continuous Auditing

- Examine Types of Audits and Control Self-Assessments (CSA)

- Understand Audit Risk, Reporting, and the Role of Data Analytics

Key Audit Standards and Frameworks

- COBIT: Provides a framework for IT governance and control.

- ISO 27001: Focuses on information security management.

- ITIL: Offers best practices for IT service management.

- NIST: Provides guidelines for cybersecurity.

- SSAE 18: A standard for auditing third-party service providers.

Introduction to the COBIT Controls Framework

- COBIT (Control Objectives for Information and Related Technologies) is a globally accepted framework established in 1996, designed to help organizations align their IT strategy with business goals.

- Developed by ISACA and the IT Governance Institute, COBIT focuses on governance and management of enterprise IT.

- With its five principles and 37 processes, COBIT provides guidance for businesses to effectively manage IT risks, optimize resources, and ensure regulatory compliance.

- It integrates with other frameworks such as Risk IT and Val IT, enabling a comprehensive approach to IT governance.

- COBIT is widely used in industries such as finance, healthcare, and manufacturing.

COBIT 5

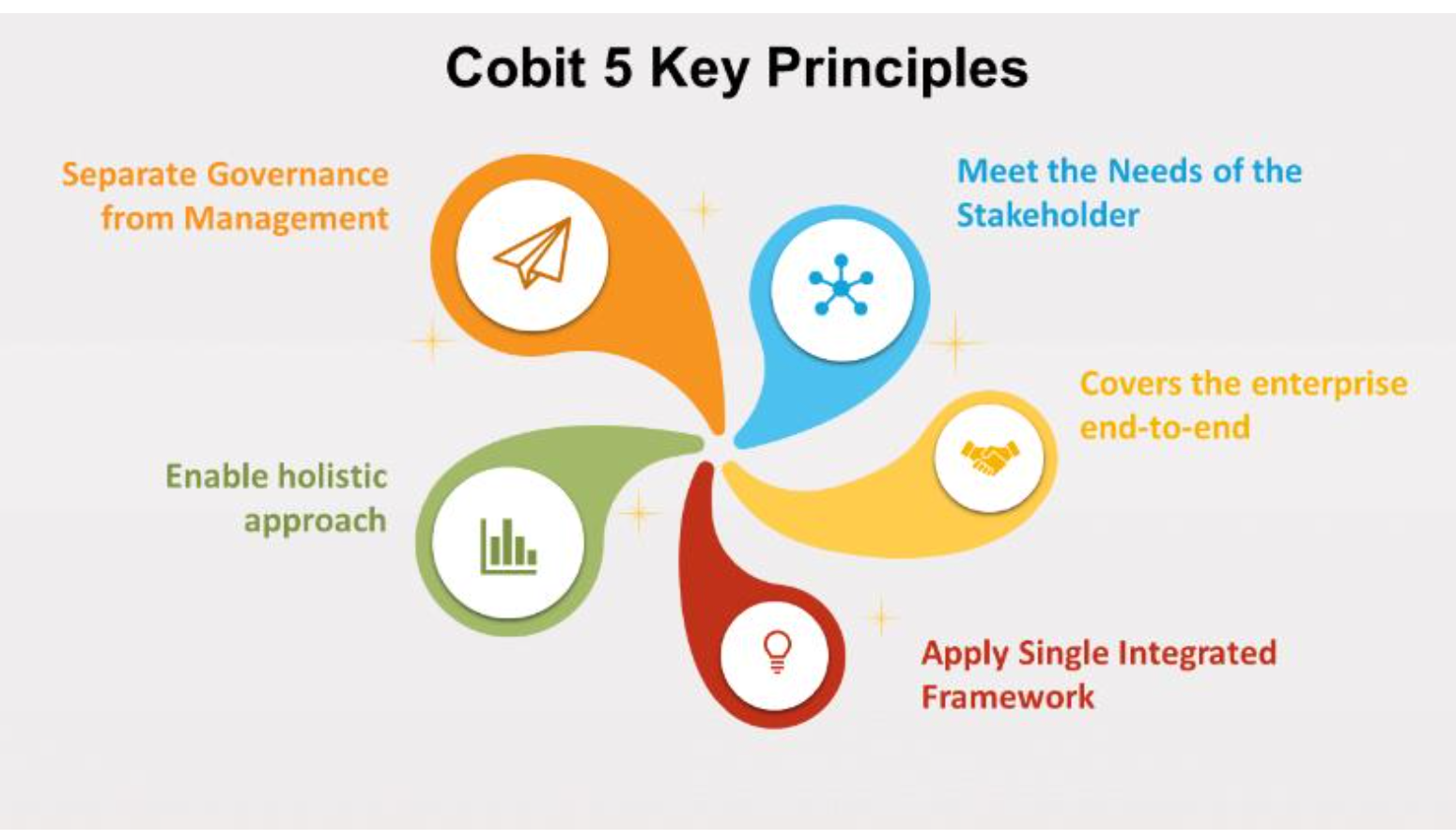

COBIT’s Five Principles

- Principle 1: Meeting Stakeholder Needs

- COBIT ensures that IT governance is aligned with stakeholder expectations by balancing risk, resources, and performance.

- Meeting stakeholder needs involves maximizing benefits while mitigating risks.

- Principle 2: Covering the Enterprise End-to-End

- This principle ensures that IT governance is integrated across the entire organization, from the strategic to the operational level.

- It covers all business areas and functions, not just IT, ensuring alignment across the enterprise.

- Principle 3: Applying a Single, Integrated Framework

- COBIT integrates various standards and frameworks into a single, cohesive structure, allowing for the unification of multiple governance frameworks under one umbrella.

- Principle 4: Enabling a Holistic Approach

- COBIT takes a holistic view of governance by involving all the enablers that contribute to effective IT management.

- These enablers include processes, organizational structures, culture, and information systems.

- Principle 5: Separating Governance from Management

- Governance and management serve different functions.

- Governance ensures that stakeholder needs are evaluated, while management focuses on executing the strategies and achieving the goals set by governance.

General Computing Controls (GCC)

- General Computing Controls (GCCs) are broad, organization-wide controls that ensure IT systems function correctly and securely.

- GCCs are implemented across various IT systems and applications to maintain consistent control over the IT environment.

- These controls are critical in areas such as user access management, data encryption, and logging of administrative actions.

- They help ensure that all systems, regardless of their specific purpose, follow uniform security and operational procedures.

- Organizations rely on GCCs to minimize security risks and ensure compliance with internal policies and external regulations.

Examples of General Computing Controls

- Password and User Access Controls

- All systems require users to have unique user IDs and strong passwords.

- Passwords must be encrypted during both storage and transmission to prevent unauthorized access.

- Data Encryption

- Sensitive information, such as financial or personal data, is encrypted at rest and in transit, ensuring that even if data is intercepted, it cannot be read without authorization.

- Logging and Monitoring

- Administrative actions are logged to ensure that any changes made to systems can be tracked. These logs are protected from tampering to ensure their integrity.

IS Controls

- IS controls refer to specific implementation details for GCCs on various technology platforms.

- For instance, password management can be implemented differently on a Linux server versus a web application.

- Each system requires unique IS controls that adhere to the organization’s overall GCCs while accommodating the capabilities and limitations of the specific platform.

- IS controls ensure consistency in the security and operation of information systems, regardless of platform differences, and are critical for maintaining the integrity and availability of IT systems.

Implementation of GCCs and Examples

- User Authentication: Applications require unique user IDs and strong passwords. Example: A bank may implement controls where Linux servers use SSH keys for authentication, and web applications require multi-factor authentication (MFA) for customers. These IS controls map to the overarching GCC for user authentication.

- Encryption: Passwords and sensitive data, such as bank account numbers, are encrypted both during transmission and storage. Example: In a healthcare environment, GCCs ensured that patient data was encrypted both in transit and at rest, reducing the risk of unauthorized access and ensuring compliance with HIPAA regulations.

- Logging: Administrative actions are logged, and logs are protected against tampering.

- Password Management A GCC for password management may involve IS controls for multiple platforms. Example: A central authentication service might enforce one set of password rules, while Linux servers and individual applications each enforce their own.

Performing an Audit

- An audit is a formal process by which an independent professional evaluates one or more controls in an organization.

- It involves gathering and analyzing evidence, interviewing personnel, and reviewing documentation to form an opinion on the effectiveness of the organization's controls.

- An IS audit focuses on information systems and the controls that govern them, ensuring that systems are secure, reliable, and compliant with regulations.

- Audits must be systematically planned to ensure a thorough and impartial review of the systems and processes in place.

Steps for Planning an Audit

There are multiple factors that needs to be considered while planning an audit.

- Purpose: Define why the audit is being conducted (e.g., compliance, risk reduction).

- Scope: Identify the specific systems, processes, or locations to be audited. This could involve specific IT systems, business processes, or a combination of both. Scope may also define geographical regions or time periods for audit focus.

- Risk Analysis: Assess the relative risk of different areas to prioritize audit resources. Risk analysis helps determine where to focus audit resources by identifying the areas of greatest risk.

- Audit Procedures: Establish procedures for evidence collection, sampling, and reporting. These procedures are informed by the audit’s purpose and scope.

- Resource Planning: An effective audit requires adequate resources, including qualified personnel, tools, and time. Auditors must estimate how many staff hours are required and what specialized tools are needed for data collection and analysis.

- Scheduling: The schedule must allow enough time for interviews, data collection, and analysis, while also meeting any external deadlines, such as regulatory reporting requirements.

Audit Objectives

- Audit objectives are specific goals that the audit seeks to achieve.

- Audits may be required by legal, regulatory, or compliance obligations, or as a proactive measure to assess control effectiveness.

- These include determining whether controls are functioning as intended, whether processes are compliant with regulations, or whether control deficiencies from past audits have been addressed.

Consider a telecom company, the objective of a recent audit was to assess the organization’s data privacy controls to ensure compliance with new data protection laws. The audit focused on how customer data was processed, stored, and protected.

Types of Audits

Operational Audit: Focuses on the operation of IS controls, examining efficiency and effectiveness. For instance, a company uses an automated inventory management system. An operational audit would examine whether this system is working efficiently to ensure that products are being restocked timely and whether the system is correctly tracking inventory levels. The goal is to ensure the process is both effective and optimized. Financial Audit: Examines the integrity of accounting processes and financial statements. Example, a financial audit of a company’s payroll system would verify whether employees are being paid the correct amounts based on hours worked and salary agreements. It would also check that the company’s financial records for payroll expenses are accurate and free of errors. Integrated Audit: Combines operational and financial audits for a complete view. IS Audit: A deep dive into IT governance, service delivery, and security processes. Example, A university implements a new student information system. An IS audit would evaluate whether the system is properly secured (data encryption, user access control) and whether it is delivering the intended services (registering students, managing records) in a secure and reliable manner. Compliance Audit: Evaluates compliance with laws, regulations, or internal policies. A hospital needs to comply with healthcare regulations (such as HIPAA in the US) regarding patient data privacy. A compliance audit would review the hospital’s data handling procedures to ensure they are following these legal requirements to protect patient information. Forensic Audit: Supports legal investigations, especially in cases of fraud or cybersecurity incidents. For instance, After a company suspects fraudulent activity in its accounting department, a forensic audit is conducted. The auditors trace financial transactions, check for any suspicious payments, and collect evidence that can be used in court to prove or disprove fraud.

Compliance vs Substantive Testing

- Compliance Testing Compliance testing focuses on verifying that control procedures are properly designed and functioning. For instance, an auditor may check if change management procedures are consistently followed.

- Substantive Testing Substantive testing examines the accuracy of transactions and data. Auditors create test transactions to verify that systems process data correctly and according to established control procedures.

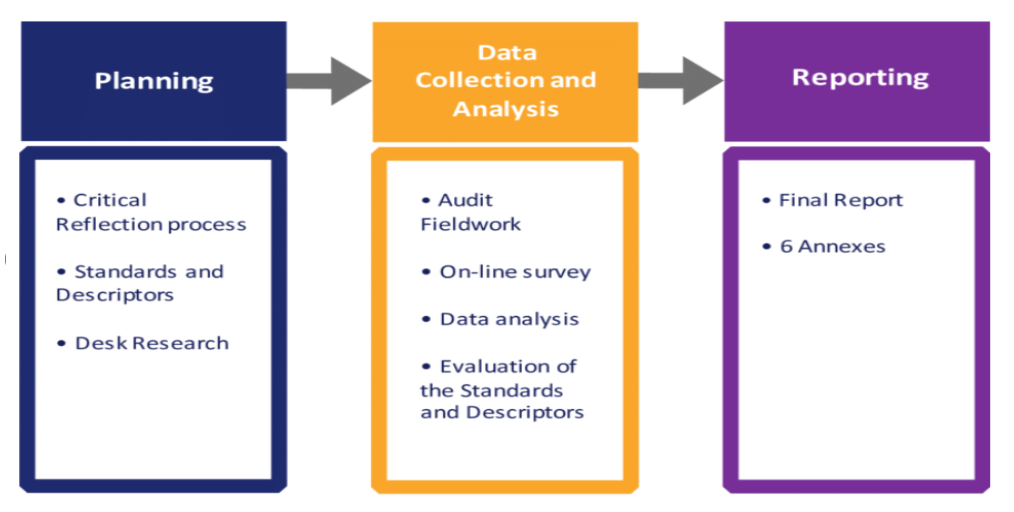

Audit Methodology

An audit methodology outlines the procedures and phases of the audit process. It ensures that audits are conducted consistently, whether by internal or external teams. A structured approach to ensure consistency and thoroughness in auditing. Audits are managed as projects with clear timelines, resources, and objectives. Involves defining the scope, objectives, and procedures of the audit.

The phases includes:

- Planning

- Evidence Collection

- Evaluating

- Reporting

Gathering Audit Evidence

- Evidence is the information collected by the auditor during the course of the audit project.

- Evidence is crucial for determining whether controls are effective and identifying any weaknesses.

- Auditors collect evidence through various methods, including interviews, reviewing system documentation, and observing processes in action.

- Personnel interviews provide insights into how controls and processes are executed.

- Auditors observe employees in their daily tasks to assess if processes align with documented procedures.

- The auditor will collect many kinds of evidence during an audit, including:

- Observations

- Written notes

- Correspondence

- Independent confirmations from other auditors

- Internal process and procedure documentation

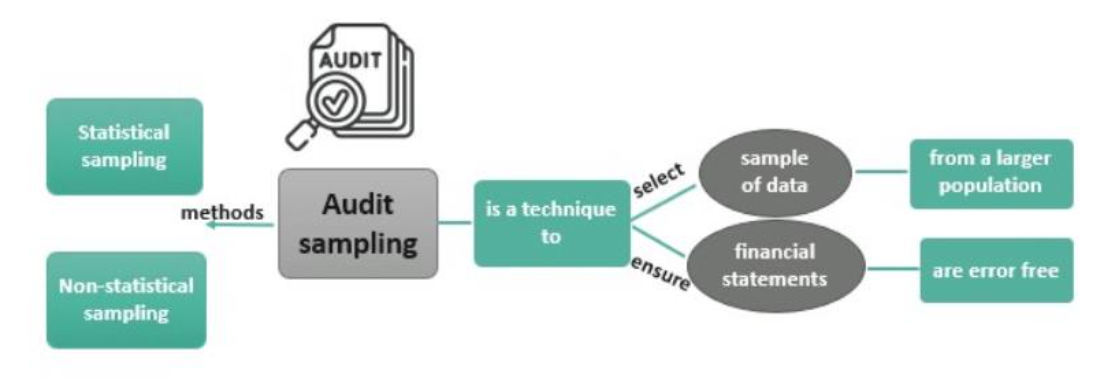

Sampling Methods in Auditing

- Statistical Sampling: Random selection of data or transactions to represent the entire population.

- Judgmental Sampling: Based on the auditor’s discretion, focusing on high-risk areas.

- Attribute Sampling: Used to study characteristics, answering questions like “How many?”

- Variable Sampling: Answers questions like “How much?” to measure the amount or extent of an activity.

Audit Reporting and Follow-Up

- After an audit is completed, the final report is delivered to the organization, summarizing findings and recommendations.

- Includes an executive summary, detailed findings, and suggestions for remediation.

- Post-audit follow-up ensures that any identified issues are addressed.

- Auditors revisit findings after a set period to ensure recommendations have been implemented.

- This phase reinforces the organization’s commitment to continuous improvement in its control environment.

Challenges in IS Auditing

- Challenges:

- Keeping up with rapidly evolving technology.

- Ensuring compliance with multiple regulatory frameworks (e.g., GDPR, PCI DSS, HIPAA).

- Accessing and analyzing large volumes of data.

- Managing audit timelines and scope.

- Identifying and mitigating cybersecurity risks.

- Solutions:

- Continuous training for auditors.

- Leveraging automated tools for data analysis.

- Prioritizing high-risk areas during audit planning.

Reliance on the Work of Other Auditors

- What?

- Organizations increasingly rely on the work of other auditors due to a lack of in-house expertise in all technological areas.

- Outsourcing audits to third-party auditors can fill knowledge gaps but requires careful management and due diligence to ensure external auditors meet necessary standards and compliance.

- Why?

- IT specialization is driving the need for external auditors.

- Internal auditors may not have the breadth of expertise required to fully evaluate complex IT environments, making third-party services essential.

Challenges in Using External Auditors

- Competence & Independence

- It's crucial to assess the technical competence of external auditors.

- They must understand the organization's systems and controls to provide accurate evaluations.

- Independence from the auditee is vital to avoid conflicts of interest, ensuring objective results.

- Potential Legal Restrictions

- Legal and regulatory frameworks may place restrictions on using third-party auditors for specific audits, especially in regulated industries such as finance or healthcare.

- Organizations need to be aware of these rules before outsourcing audits.

Impact of Outsourcing Audits

- Cost Implications Outsourcing audits often results in additional costs, but it can free internal resources for other tasks. However, organizations must weigh these costs against the benefits, ensuring the expense of external auditors is justified by the value they bring.

- Risks External audits introduce risks, such as dependence on external auditors' quality of work and timeliness. External auditors also require access to sensitive data, creating potential privacy and security concerns that need to be managed.

Reliance on Third-Party Audit Reports

- Third-Party Audit Reports Organizations often depend on third-party audit reports when using external service providers. For instance, when an organization outsources payroll, they might rely on the provider’s SSAE 18 audit instead of conducting their own, reducing the audit burden on internal teams.

- Benefits and Challenges While relying on third-party audit reports can save time and resources, organizations must ensure the reports meet their own audit standards and legal requirements, and that they accurately reflect the provider’s control environment.

Audit Data Analytics

- Audit data analytics refers to the use of advanced computational techniques to analyze large data sets for audit purposes.

- These techniques help auditors assess control effectiveness by identifying patterns, anomalies, and potential risks within the data.

- For example: Cross-referencing badge access records with system login data to detect suspicious logins is an example of using audit data analytics to assess user behavior and access control effectiveness.

Computer-Assisted Audit Techniques (CAATs)

- CAATs enable auditors to handle large data sets and complex environments.

- These tools automate data extraction, analysis, and reporting, making it easier for auditors to assess system controls in complex IT environments.

- Common CAATs include

- database extraction tools,

- test transactions,

- code scanning,

- debugging software.

- Each tool is used to assess different aspects of IT systems, such as transaction processing, code security, and database integrity.

Test Transactions in Audit

- Test transactions are artificially created transactions that auditors use to verify the accuracy of system processes.

- Auditors input known data into a system and compare the results with expected outcomes to assess system reliability and control effectiveness.

Example: An auditor might create test payroll transactions to verify that deductions, taxes, and payments are processed correctly. If the system produces the expected results, it confirms the accuracy of payroll calculations.

Automated Work Papers

- Automated work papers are digital records generated by audit tools like CAATs.

- They document evidence gathered during an audit and must be stored securely to maintain their integrity and confidentiality.

- Protecting automated work papers involves encryption, strict access controls, and regular backups.

- These measures ensure that audit evidence cannot be tampered with and remains available for future audits or regulatory reviews.

Generalized Audit Software (GAS)

- Definition: GAS refers to computer programs designed to assist auditors in performing a variety of audit tasks, especially those involving large amount of data.

- Generalized Audit Software (GAS) allows auditors to directly access and analyze data from systems without relying on the system's built-in reports.

- GAS provides a flexible and independent way for auditors to verify the accuracy and completeness of data.

- By using GAS, auditors can independently extract data samples, run custom queries, and analyze system transactions without relying on potentially biased system-generated reports.

- Popular examples of GAS: ACL and IDEA

Continuous Auditing

- Continuous auditing involves the regular and automated collection of audit data over time, allowing organizations to monitor controls more effectively and detect issues as they occur rather than during periodic audits.

- Continuous auditing helps identify control failures and exceptions in real-time, allowing organizations to respond quickly to potential security incidents, policy violations, or fraud attempts before they escalate.

- Audit Hooks:

- Audit hooks are embedded in software applications to monitor transactions continuously. They generate alerts when specific conditions are met, such as a potentially fraudulent transaction or a security breach.

- For Instance, An audit hook in a financial system might trigger an alert if a large transaction occurs outside normal business hours, allowing auditors to investigate potential fraud or policy violations in real-time.

Integrated Test Facility

- ITF involves creating dummy test records within a live production environment to verify that the system processes both real and test transactions accurately.

- These test records help auditors assess the system’s ability to handle transactions properly.

- ITF allows auditors to continuously monitor systems without interrupting daily operations, ensuring that control mechanisms work as intended while business transactions are processed.

For example: In an online banking system, auditors may set up a fictitious customer account with test transactions like deposits, withdrawals and transfers. The ITF allows the auditors to ensure that the banking system is calculating the interest correctly, processing transactions according to set rules, and updating balances accurately.

Continuous and Intermittent Simulation (CIS)

- CIS involves simulating real transactions in a production environment to compare the simulated results with actual outcomes.

- This helps auditors verify that controls are functioning correctly during live transaction processing.

- CIS is especially useful in financial systems where auditors need to verify the accuracy of large-scale transaction processing, such as bank transfers or stock trading, without affecting the real transactions.

System Control Audit Review File (SCARF)

- What is SCARF?

- SCARF involves embedding specialized audit modules into production systems.

- These modules monitor transactions and control activities, providing real-time feedback on system performance and potential issues.

- Embedded Audit Modules (EAM)

- EAMs are part of SCARF and continuously log transaction data, providing auditors with a detailed view of system behavior and helping detect exceptions such as unauthorized access or unusual transaction patterns.

Reporting Audit Results

- An audit report must include:

- a cover letter,

- an introduction,

- a summary of findings,

- a detailed description of audit procedures,

- list of evidence collected.

It concludes with an auditor's opinion and recommendations.

Also, the findings section of an audit report should provide a detailed analysis of control effectiveness, highlighting both successful controls and deficiencies that need remediation. Recommendations should be actionable and aligned with the organization's business objectives.

Audit Reports: No Surprises Rule

- Building Trust Through Communication In a well-managed audit, findings should not come as a surprise to management. Throughout the audit process, auditors should maintain open communication with management, ensuring that any issues are addressed as they arise.

- Transparency By keeping auditee management informed of preliminary findings and issues, auditors foster a collaborative relationship that helps reduce friction during the final report presentation.

- Role of Auditors in Detecting Fraud While detecting fraud isn’t the primary responsibility of IS auditors, they are in a unique position to identify potential fraud by analyzing patterns in transaction data and identifying irregularities.

- Fraud Detection Techniques Auditors can detect fraud by analyzing large transaction datasets using CAATs, performing substantive testing, and looking for unusual patterns, such as excessive refunds, duplicate transactions, or unauthorized access to systems.

Audit Risk and Materiality

- Audit Risk Types Audit risk consists of control risk (the risk that controls fail), detection risk (the risk that auditors fail to detect issues), and inherent risk (the risk present due to the nature of the business or system). Sampling risk is another important consideration.

- Materiality In financial audits, materiality refers to the threshold at which a control deficiency or error could significantly affect financial statements. In IS audits, materiality is evaluated based on the potential for system failures to lead to significant operational or security risks.

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative Risk Assessment A qualitative risk assessment rates risks as high, medium, or low, while a quantitative assessment uses numerical data to estimate the likelihood and financial impact of risks. Both methods help auditors prioritize high-risk areas for audit focus.

- Example A qualitative assessment might flag unauthorized access as a high risk, while a quantitative assessment would estimate the potential financial loss if that risk were realized.

Control Self-Assessment (CSA)

- Definition

- Control Self-Assessment (CSA) is a method where departments self-evaluate their own internal controls, risks, and processes.

- This allows organizations to proactively manage risk without relying solely on external audits, fostering a culture of internal accountability and continuous improvement.

- Example An organization may conduct CSA workshops to identify risks in its procurement process, where staff identifies areas where controls could be improved to prevent fraud or operational inefficiency.

Advantages vs Disadvantages of CSA

Advantages

- Benefits of CSA CSA empowers employees to take responsibility for the controls within their department, leading to earlier detection of risks and faster implementation of control improvements. It also raises awareness of controls and strengthens relationships between internal teams and auditors.

- Increased Ownership Since employees are directly involved in assessing and improving controls, there is a greater sense of ownership and accountability, which can lead to more effective and sustainable control environments.

Disadvantages

- Potential Pitfalls CSA can be mistaken as a substitute for formal audits, leading to a false sense of security. Employees may also be tempted to underreport issues to avoid repercussions or additional work, reducing the effectiveness of self-assessments.

- Bias Risk There is a risk that employees may be less objective when assessing their own controls, introducing potential bias into the evaluation process. Organizations need to balance CSA with independent external audits to ensure thorough oversight.

The CSA Life Cycle

- Phases of CSA The CSA life cycle consists of identifying risks, assessing controls, conducting workshops or distributing questionnaires, analyzing results, and implementing control improvements. This iterative process ensures that controls are continuously evaluated and enhanced.

- Awareness and Training Throughout the CSA process, awareness training is critical to ensure that staff remains informed about risks, control expectations, and any changes in procedures. This helps maintain a proactive control environment.

- Objectives of CSA The primary goal of CSA is to shift responsibility for control monitoring to the control owners, allowing them to take proactive steps in improving and maintaining their controls. This creates a more agile and responsive risk management culture.

- Long-Term Impact Over time, CSA aims to reduce the number of audit exceptions and foster a culture of compliance, where control deficiencies are addressed before they escalate into major issues.

Implementation of Audit Recommendations

- Importance of Implementation Successful audits don't end with the audit report. Auditees must act on the recommendations provided by auditors to improve controls and mitigate identified risks. This phase is crucial to ensuring that audit findings lead to meaningful organizational improvements.

- Collaborative Process In many cases, auditors work closely with auditees to ensure that recommendations are practical and achievable, creating a spirit of partnership rather than adversarial oversight.

- Common Challenges Implementing audit recommendations can be hindered by budget constraints, resource limitations, and resistance to change. Additionally, auditees may prioritize other operational goals over the audit findings, delaying remediation efforts.

- Strategies for Success Effective implementation requires clear communication, dedicated resources, and support from senior management. Organizations must prioritize high-risk findings and ensure they are addressed promptly to avoid future incidents.

Summary

- COBIT Framework

- General Computing Controls

- IS Audits

- Types of Audits

- Control Self-Assessments

- Audit Risk and Reporting

- Data Analytics in Audits