Chapter 5: Transportation Cyber- Physical Systems Security and Privacy

GOOGLE DATA CENTER SECURITY: 6 LAYERS DEEP

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kd33UVZhnAA

WHY YOU MUST SECURE YOUR CYBER-PHYSICAL SYSTEMS

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7h8sfg9yNTs

OBJECTIVES

- Introduction

- Basic concepts

- Threats and vulnerabilities in Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems

- Security models for Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems

- Applied security controls in Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems

- Use case: connected car

- Emerging technologies

- Conclusions and future direction

1. INTRODUCTION

Transportation cyber-physical systems (TCPS) have the potential to generate, process and exchange significant amounts of security-critical, safety-critical and privacy-sensitive information, which makes them attractive targets for cybercriminals.

TCPS utilise a wide variety of software, hardware and physical components, interconnected by communications protocols.

Computational and physical components (e.g., sensors and actuators) often interface with humans, and include a mix of digital and analog subsystems, with interactions in real time (especially where safety and time-critical functions are needed).

Cyber-physical systems will underpin critical infrastructure, intelligent transport systems and autonomous vehicles and form the basis for emerging smart city fabrics.

TCPS integrate a broad range of immature and proprietary technologies, incomplete (or missing) standards, and components that may have little or no security built in by design.

Whilst the focus is still very much on safety, the industry is now waking up to the idea that safety cannot be assured without security, and we must incorporate best security practises into TCPS projects from the outset.

The complexity, heterogeneity and immaturity of TCPS leave them vulnerable to new classes of cyberthreat, with attacks that have the potential to cause significant physical and economic damage, as well as threaten human lives.

2. BASIC CONCEPTS

TCPS will become a critical part of national infrastructure, where the risks exposed have the potential to become national or even global issues.

TCPS overlap with a number of domains and yet introduces new paradigms: however, there are important lessons to be learnt from cybersecurity best practices in traditional infrastructures such as enterprise, Telco and industrial.

The fundamental security issues raised by TCPS are not necessarily new; however, advances in technology, increased use of low-power components (often with weak security controls) and new service models make it important to employ a different approach to protect data, people and infrastructure against emerging threats.

New vulnerabilities will continue to be exposed and exploited, and given the potential attraction of TCPS to adversaries (ranging from lone hackers, organised crime, to nation-state sponsored groups), we should anticipate that ever more sophisticated threats will continue to surface.

2.1 THREATS

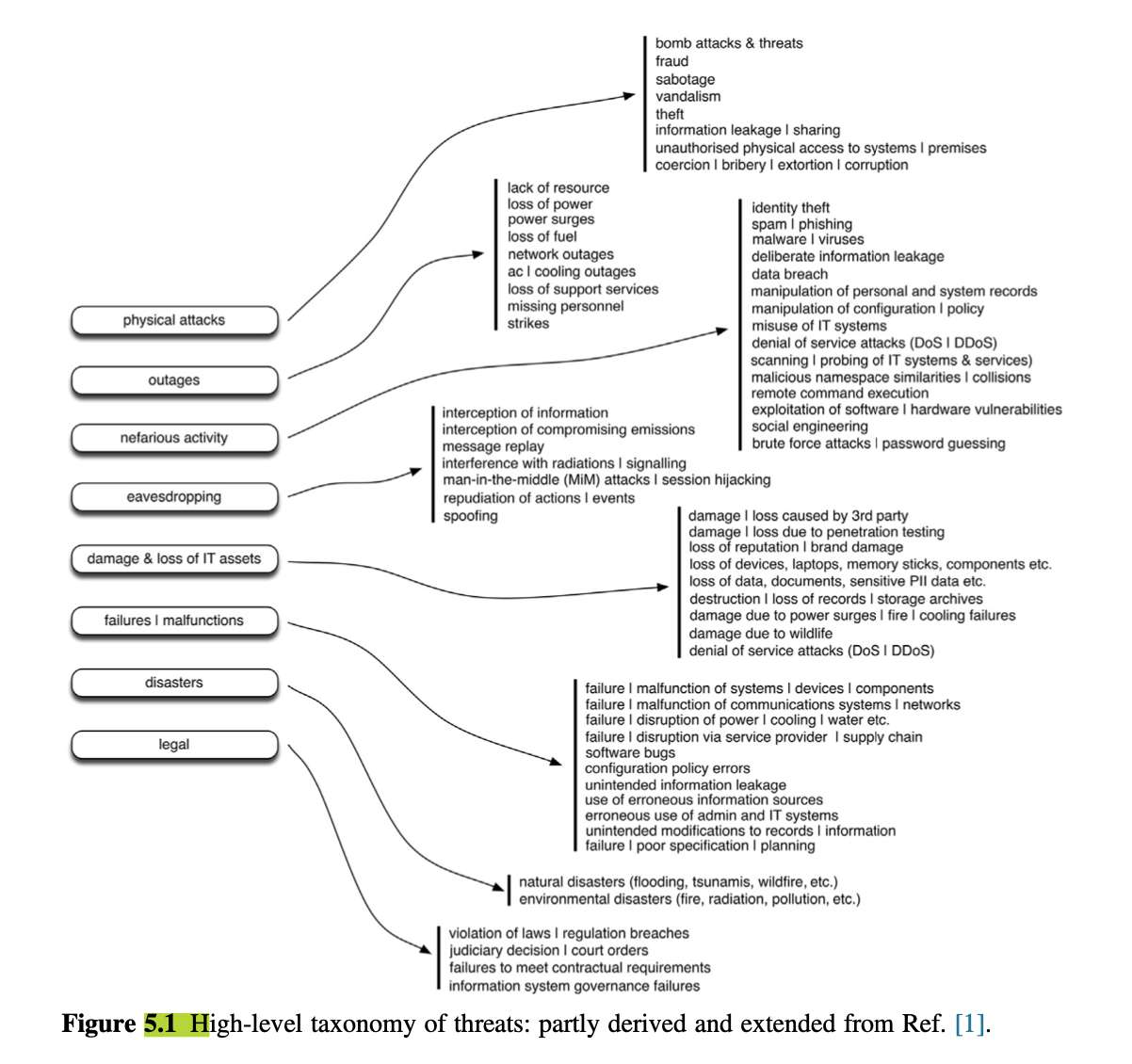

- At a high level we can consider a threat taxonomy that has significant overlap with many other domains.

- Fig. 5.1 provides a high-level classification for threat classes, partly based on work by the European Union Agency for Network and Information Security.

- Most of these threat classes are applicable to TCPS, although their relative ease, frequency and implementation will vary depending upon the specific transport domain and systems deployed.

2.2 ADVERSARIES

In cybersecurity, adversaries exist in several forms (often referred to as profiles), and they should be considered individually when assessing the scope of risk, vulnerability and threat.

We may consider a number of important classifications and attributes when profiling an attacker, such as the following:

- Powerful or weak adversary (e.g., lone actor, computer expert, organised crime, statesponsored teams of experts)

- Resources available to adversaries (e.g., access to finance, machines, malware tools) - External or internal to the system (e.g., remote attack or installed keylogger)

- External or internal to an organisation (e.g., insider threat, social engineering)

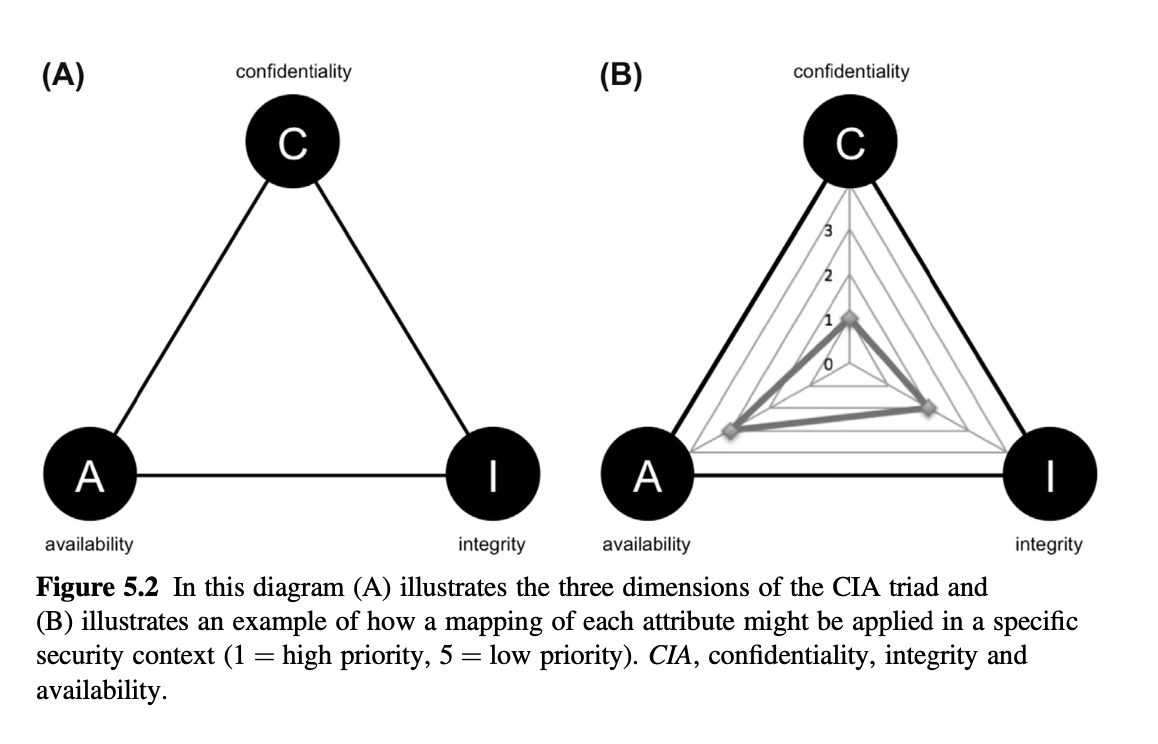

2.3 CONFIDENTIALITY, INTEGRITY AND AVAILABILITY

2.4 RISK

Cybersecurity is not simply about cryptography; it is about assessing the risk of undesirable actions happening in a given context, and deploying appropriate safeguards and countermeasures (security controls) to militate such risk.

In enterprise security, for example, we may use a method called annual loss expectancy (ALE) to quantify and manage risk, which broadly follows the methodology listed below:

- Identity and prioritise assets (e.g., business-and mission-critical systems, intellectual property, personally identifiable information (PII), customer contact lists, etc.).

- Identify major threats and vulnerabilities.

- Estimate the probability of threats against the value of asset being compromised (using probabilities which often rely on domain expertise or industry datasets). This is referred to as the Single Loss Expectancy (SLE). SLE is calculated as: SLE = Asset value * Exposure factor (EF).

- Estimate the Annual Rate of Occurrence (ARO) to determine the likelihood of each class of threat per year. 5. Using the previous two metrics we can determine the Annual Loss expectancy (ALE) to estimate the risk exposure for each asset class. ALE is calculated as:

ALE = SLE * ARO.

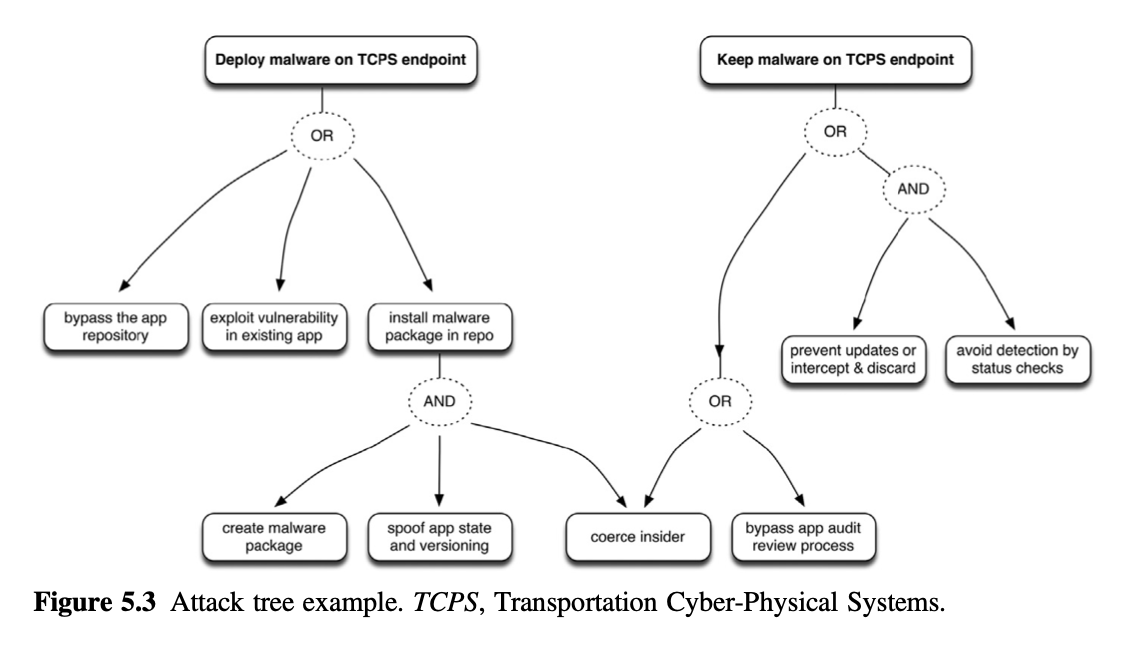

2.5 ATTACK TREES

2.6 KILL CHAINS

Table 5.1 Key Steps and Actions in Lockheed Martin’s Cyber Kill Chain

d

| Step | Title | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reconnaissance | Probe and collate addresses, unsecured ports, etc. |

| 2 | Weaponisation | Assemble and code malware package and delivery methods |

| 3 | Delivery | Deliver weaponised package to victim (e.g., e-mail malware attachment) |

| 4 | Exploitation | Exploit vulnerabilities to compromise remote assets |

| 5 | Installation | Install malware on target asset(s) |

| 6 | Command and control (C2) | Command channel for remote manipulation of target |

| 7 | Actions on objectives | Adversaries achieve their goal using C2 |

2.7 SECURITY CONTROLS

- Predictive controls:

- trend analysis, machine learning (ML) and statistical techniques on historical data, early warning systems

- Preventative controls:

- access controls, firewalls, antivirus (AV) software, intrusion prevention systems (IPS), defensive coding, security policies and processes

- Detection controls:

- intrusion detection systems (IDS), security information and event management systems (SIEM)

- Corrective controls:

- to correct or limit the impact of damage after the event (e.g., disaster recovery, rollback procedures, incident response processes)

- Privacy controls:

- secure channels (encrypted links, virtual private networks (VPNs), etc.)

- Audit and analytical controls:

- logging and reporting tools, laws and regulations, etc.

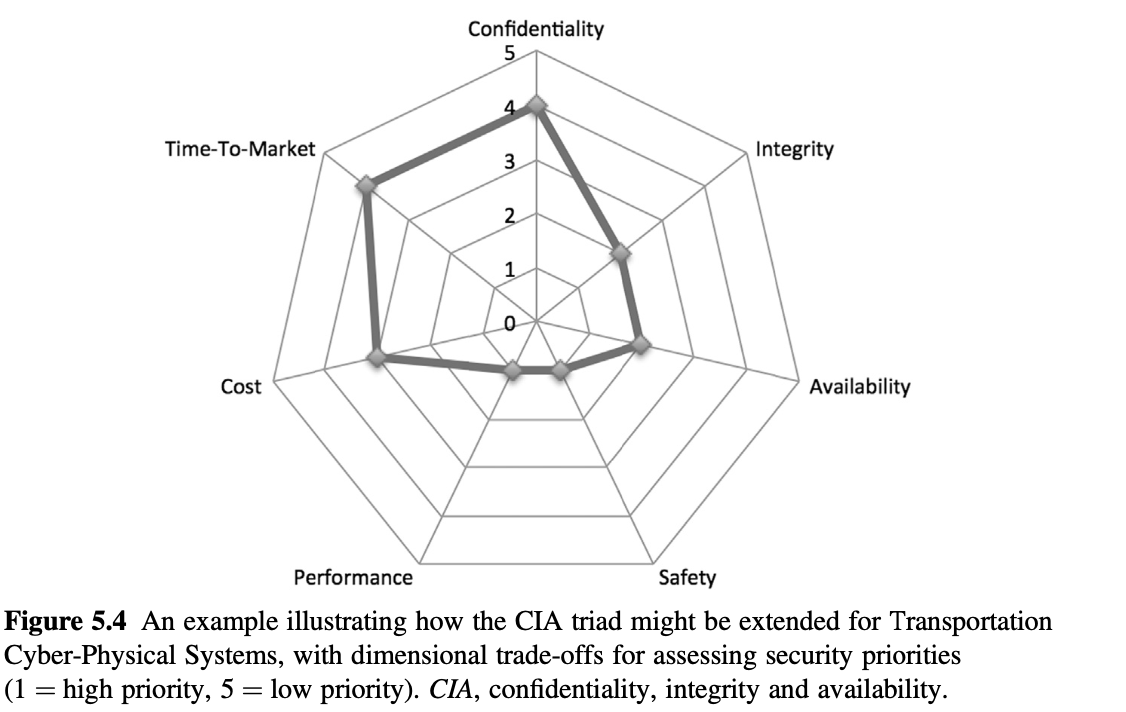

2.8 EXTENDING THE CONFIDENTIALITY, INTEGRITY AND AVAILABILITY TRIAD

Figure 5.4 An example illustrating how the CIA triad might be extended for Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems, with dimensional trade-offs for assessing security priorities (1 = high priority, 5 = low priority). CIA, confidentiality, integrity and availability.

Figure 5.4 An example illustrating how the CIA triad might be extended for Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems, with dimensional trade-offs for assessing security priorities (1 = high priority, 5 = low priority). CIA, confidentiality, integrity and availability.

3. THREATS AND VULNERABILITIES IN TRANSPORTATION CYBER-PHYSICAL SYSTEMS

3.2 ATTACK SURFACES

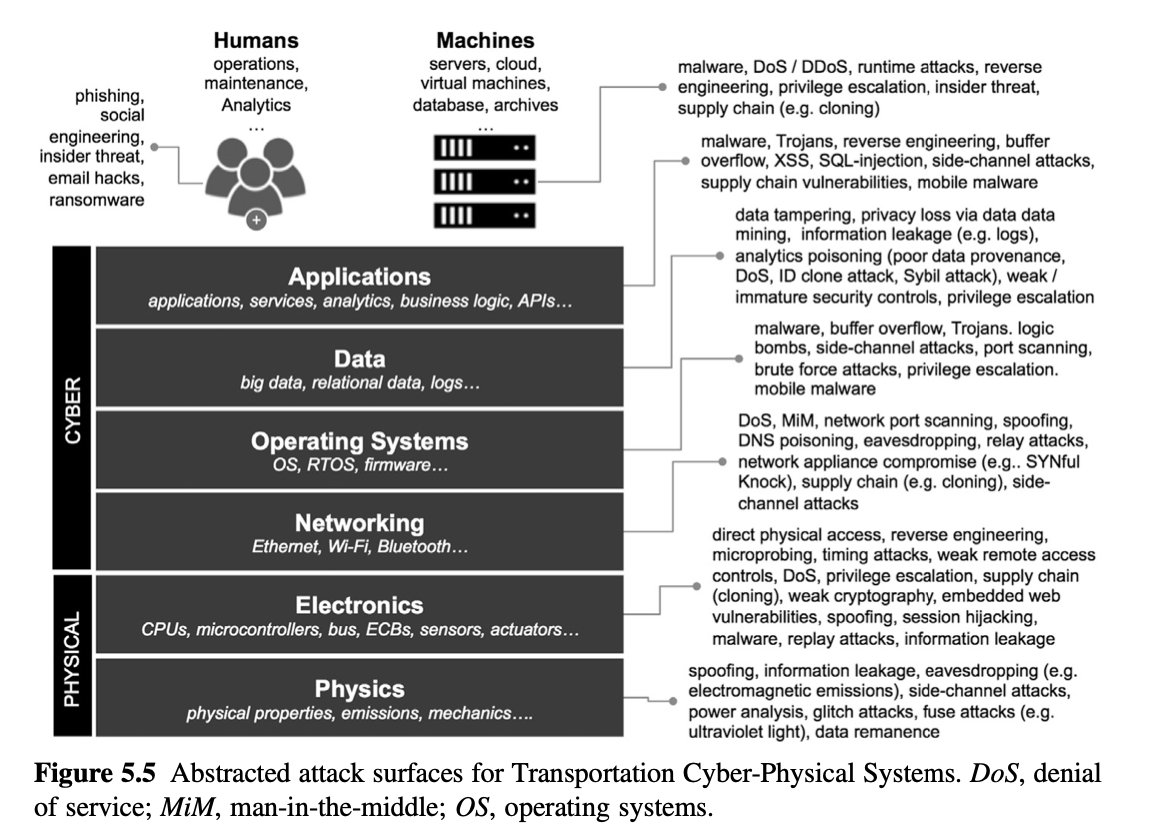

Figure 5.5 Abstracted attack surfaces for Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems. DoS, denial of service; MiM, man-in-the-middle; OS, operating systems.

Figure 5.5 Abstracted attack surfaces for Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems. DoS, denial of service; MiM, man-in-the-middle; OS, operating systems.

3.3 RELIANCE ON SENSORS AND WI-FI

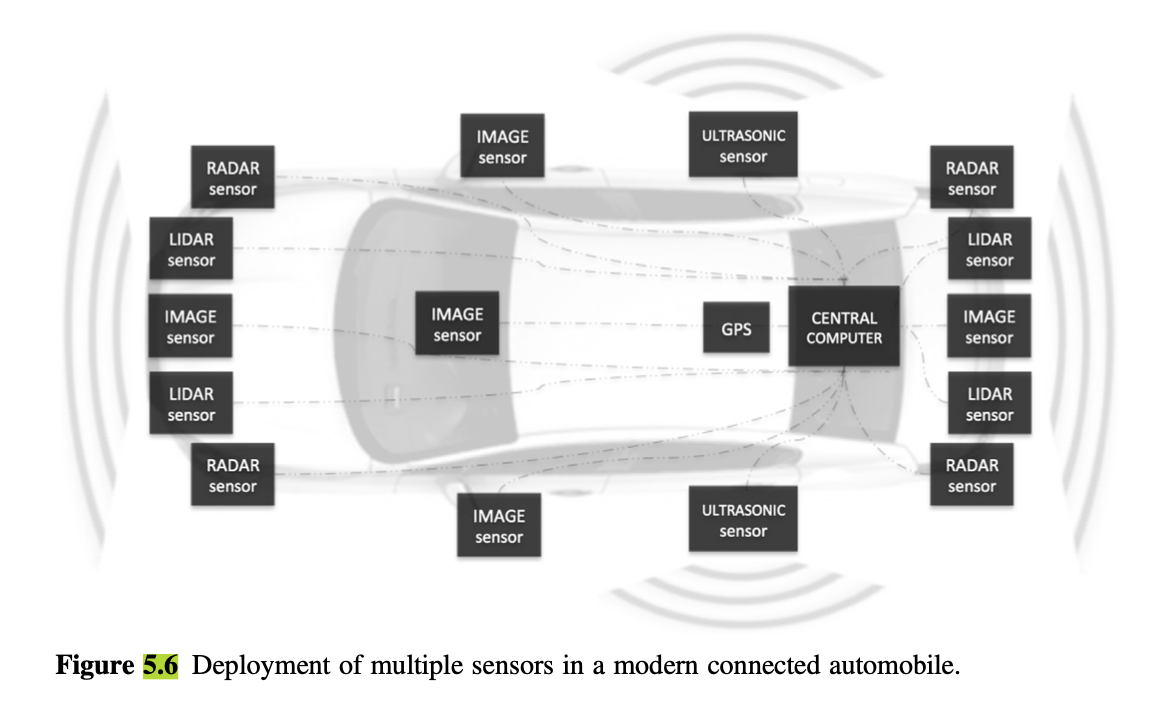

- Modern vehicles currently have an average of 60 -100 onboard sensors, and as cars become increasingly intelligent the number of sensors is projected to reach over 200 per vehicle by 2020.

- Today’s systems for semi-autonomous driving use a variety of radar and camera systems.

- Autonomous vehicles demand complex integration, with sophisticated algorithms running on powerful processors used to make critical decisions from large streams of realtime data, generated by a diverse and complex array of sensors.

- Modern commercial aircrafts have potentially thousands of onboard sensors, generating terabytes of data per day.

- Whilst the majority of aircraft engines have fewer than 250 sensors, this is changing quickly: for example, Pratt & Whitney’s geared turbofan engine has around 5000 sensors, generating up to 10 GB of data per second.

- The Airbus A380-1000 will be equipped with 10,000 sensors in each wing alone, with reportedly 250,000 sensors in total.

4. SECURITY MODELS FOR TRANSPORTATION CYBER-PHYSICAL SYSTEMS

4.1 CHALLENGES

Some of the broader challenges in building secure TCPS infrastructures are highlighted in the following:

- Systems are typically complex, heterogeneous and incorporate physical, ‘soft’, digital and analog components from many different suppliers. This represents a large attack surface and there may be insufficient knowledge, training and skills to design and operate effective security solutions.

- Important technologies used in TCPS are not all publically documented or peer reviewed, which significantly constrains vulnerability analysis and research opportunities and presents opportunities for reverse engineering of potentially weak or obfuscated security features.

- Real-time constraints are particularly challenging when trying to overlay security controls and may require purpose-built operating systems (OS) and refactored security techniques.

- Manufacturers and developers consistently underestimate security risks and vulnerabilities in the race to gain install base and market share.

- The focus on safety, without sufficient attention on security, has the potential to seriously compromise safety itself.

- Existing security and privacy models may be inadequate or even impractical for sensors and microprocessor-based devices with limited resource.

- Traditional perimeter-based approaches to security may be entirely inappropriate in some TCPS contexts, particularly where direct physical access to a system is possible.

- New vulnerabilities will be exposed due to unique deployment and maintenance processes and systemic immaturity.

- Advances in ML may help with TCPS security automation and efficacy may be hampered by lack of training data.

4.2 SECURITY ARCHITECTURE

We must consider several different perspectives and challenges including the following:

- Identifying and mitigating specific TCPS threats at a domain level (intelligent transport systems, air traffic control, high-speed intelligent rail, autonomous vehicle, etc.)

- Improving and developing new security standards, regulations and protocols that are feasible and applicable in a TCPS context

- Tolerance to faults, noise and intrusion (especially for real-time safety-critical systems), without compromising overall safety and integrity

- The ability to transfer or adapt best-practice security controls in low-power embedded contexts (e.g., embedded firewalls, lightweight security protocols and device attestation techniques)

- How to protect, detect and manage privacy breaches and sensitive data leakage

- Sensor state integrity and end-to-end provenance of telemetry data

- Mobility issues with data portability (e.g., cross-border legislative concerns)

- Protection of interfaces and trust boundaries between the physical environment, sensors and upstream control systems • Improvements in formal verification, simulation modelling and test in a TCPS security context

4.3 SITUATIONAL AWARENESS

From a cybersecurity perspective, we want to know the following:

- Is the system in a known acceptable state (software, firmware revisions, configuration files, policies, access control lists, etc.)?

- Is the system behaving as expected, or exhibiting anomalous behaviour?

- Are there indications that the system may have been breached or compromised?

- Is information or telemetry being intercepted, leaked, missed or delayed?

- Are we able to baseline what ‘normal behaviour’ looks like, and is this baseline changing over time?

- Can we predict future failures or additional resource needs using current behaviour and instrumentation?

4.4 SECURITY CONTROLS

In TCPS, security controls fall into three main categories:

- Reusable: controls that can be directly reused from existing security domains: for example, the use of security policies, firewalls, IDS, IPS, AV and VPNs. These may be directly transferrable to back-end TCPS control and support infrastructure.

- Refactored: controls that must be refactored for application in the constrained environment of TCPS (such as lightweight embedded firewalls and hardware security modules (HSMs)).

- Novel: controls designed to deal with the specific challenges and threats in TCPS (such as new models for intrusion tolerance, new methods for large-scale device attestation, etc.)

4.5 PRIVACY

Privacy tends to focus on questions such as the following: • What information should be collected?

- With whom is this information to be shared?

- What are the permissible uses?

- How long should the information be retained?

- What level of granularity is appropriate for the access control model? •

- How can permission to use this information be revoked?

Some of the many privacy challenges in TCPS therefore include the following:

- Whether all such data should (or even can) be encrypted?

- Whether data can be intercepted and modified, and if so what controls are in place to detect such events?

- Whether data can be reconstructed or analysed to reveal more sensitive personal information (for example, using big data inferences)?

- Whether a device can be compromised and used maliciously from a remote location (for example, to eavesdrop or leak sensitive information)?

- What regulations and safeguards are being adhered to, especially as TCPS endpoints are often mobile (e.g., vehicles move across national boundaries)?

4.7 EMERGING STANDARDS

New standards are being introduced by the IETF, the International Standards Organisation (ISO) and other standards bodies. Examples include the following:

- Continuous Air Interface for Long and Medium Range: an ISO initiative defining standard wireless protocols and interfaces for Intelligent Transport System (ITS) services.

- Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP): a lightweight Hypertext Transport Protocol Secure (HTTPS)-like protocol.

- Object Security for CoAP: for securing CoAP messages.

- Concise Binary Object Representation (CBOR): human-readable data representation of keyevalue pairs and array data types (similar to JSON but more compact).

- CBOR Object Signing and Encryption: for securing CBOR objects.

5. APPLIED SECURITY CONTROLS IN TRANSPORTATION CYBER-PHYSICAL SYSTEMS

- Current cyber-physical security research tends to rely heavily on existing security controls and design patterns.

- Due to the specific demands of TCPS this approach may be inappropriate in some key contexts such as large-scale low-end embedded environments, real-time safety-critical environments, and unattended targets with poor physical security.

- Further research and development is required and it is likely that novel solutions specific to TCPS will be required.

- Factors such as real-time demands, feedback between network, physical and human actors, distributed command and control, uncertainty around behaviour and threat models, limitations in test and simulation, scalability and geographic distribution must be considered holistically in cyberphysical security design.

- Neuman discusses security modelling, security of sensors and actuators, system architecture and application security in CPS and offers a design method for integrating security into core system design.

6. USE CASE: CONNECTED CAR

- Vehicles today contain a mixture of analog and digital components, and to a large extent the driver is still in charge.

- Automation in vehicles is now receiving a huge amount of attention from both the research community and manufacturers, with product offerings announced by powerful companies such as Google, Apple, Microsoft, Uber and Tesla.

- As we migrate towards fully connected and ultimately autonomous vehicles, the risk of a serious attack will inevitably increase.

- Eventually there may be few to no human-accessible controls, as manufacturers move to reduce cost and complexity, with the ability to manually override driver functions removed.

- If a network of such vehicles was to be compromised, the risk of serious incident at both an individual and macroscale becomes quite probable.

- It would be unwise to ignore such possibilities, and experience from other fields demonstrates that retrofitting security (as is currently happening in some areas of TCPS) rarely works.

- Whilst the industry focuses on safety, we need to significantly improve security from the ground up, building in security and privacy controls at the design phase, investing in associated research, improving standards and introducing targeted regulation.

6.1 KEY STAKEHOLDERS

The key stakeholders for connected vehicle are listed as follows:

- Private vehicle owners

- Vehicle manufacturers

- Vehicle dealers

- Service providers

- Fleet owners and leasing companies • Software and hardware companies

6.2 SYSTEM AND COMPONENT ARCHITECTURE

7. EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES

7.1 SOFTWARE- DEFINED NETWORKS

Effective cybersecurity remains a hard problem, even in less-complex environments such as enterprise networks; it remains a problem very far from solved.

There are simply too many variables and too many dynamics in the threat and vulnerability landscape, including (and often compounded by) interaction with people.

SDNs are essentially a new approach to network orchestration, pushing core routing intelligence out to the edge of the infrastructure, away from traditionally smart switches and routers.

The basic idea is that the network should comprise less- intelligent systems at the core, but these can be rapidly reconfigured to respond to changes in the environment through programmable policies.

7.2 VIRTUALISATION

Virtualisation is essentially the capability to deploy OS and components inside tightly controlled software containers to be executed over virtual machines, and is proving to be highly advantageous for rapid deployment of so-called elastic support infrastructures for data centres and back end support services.

Virtualisation speeds up deployment and improves security by assuring consistency across multiple OS instances.

Virtualisation is also a fundamental component of the new ‘DevOps’ approach to software deployment and is likely to be a key enabler for software-defined infrastructures.

Virtualisation promotes sandboxing (containing execution of sensitive or risky functions within a container), scale, out and high availability.

These properties are very attractive for building cost-effective, secure and agile TCPS infrastructure. Virtualisation is likely to have other benefits in TCPS, such as improved testing and simulation, dynamic rollback of critical systems to a known state and rapid deployment of stable and consistent in-vehicle systems.

7.3 BIG DATA

TCPS infrastructures produce vast quantities of data, and the volume and velocity of these data may be infeasible to store and analyse using traditional relational databases.

Big data (in the form of Apache Hadoop, Cassandra and other ‘NoSQL’ technologies) enables very large unstructured datasets to be held in high-availability processing clusters.

With technologies such as Hadoop, large volumes of unstructured data can be efficiently queried using specialised techniques such as MapReduce, and this ability to span huge amounts of loosely structured data can often reveal surprising insights.

In the context of TCPS we should expect to see big data being used heavily in back end support infrastructure, to hold and analyse messaging, telemetry, event logs, geospatial data, even video feeds and images.

Where TCPS networks are software programmable, it may also be possible to create feedback loops where insights become actionable with dynamic changes to such networks dynamically orchestrated - in response to changes in demand, for example, or as a result of predictive analytics.

7.4 ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND MACHINE LEARNING

- Since cybersecurity breaches and compromises are practically inevitable and the consequences of these breaches in TCPS are potentially life threatening, we will need to find several advances in improving the intelligent of such networks and systems.

- TCPS infrastructures are required to be somewhat intrusion tolerant and will need to provide rapid self-healing, alongside new levels of automation.

- At the analysis phase, ML (together with blended heuristics) is likely to offer important insights and benefits in the automation of threat and vulnerability analysis.

- Intelligent systems and anomaly detection also have an important roll to play in differentiating normal and delinquent behaviour, both at the control system level and at the sensor-actuator level.

- ML and techniques such as neural networks (NNs) and fuzzy logic may help differentiate between faulty, failing or misconfigured or compromised components.

- ML and NNs may also be trained to predict future failures based on existing behaviour.

- This shift towards a smarter and more proactive security posture could have significant benefits in traditional security contexts such as industrial and enterprise systems.

7.5 BLOCKCHAIN

Blockchain is a relatively new technology based on well- established concepts (such as Merkle trees and hash codes) and brings together the functions of distributed consensus, immutable state, timestamping and distributed ledgers.

Perhaps the bestknown implementation of blockchain today is Bitcoin, and while Bitcoin is based on blockchain technology it is important to differentiate between blockchain fabrics and the implementation of digital currencies and tokens on those fabrics.

Blockchain fabrics have many potential uses across a wide range of industries and contexts, and research that predates Bitcoin introduces the application of time-stamped calendar blocks that now underpin many blockchain implementations.

There have been proposals to use blockchains in many security and privacy contexts, for example, to register immutable asset states, maintain the integrity of audit logs, assure the provenance of sensitive telemetry, protect health records and assure PII transaction integrity for GDPR.

8. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTION

TCPS represent a unique and broad attack surface for cybercriminals, and by incorporating unprotected technologies into emerging connected designs we run the risk of serious incidents in the future.

As we have discussed, in TCPS the consequences of compromise are potentially life threatening and may have significant direct and indirect economic risks, as well as risks to individual privacy.

A holistic cybersecurity approach with multiple abstraction levels is required to address the unique security and privacy risks associated with TCPS. Furthermore, specific domains within TCPS exhibit marked differences in design, implementation and risk appetite and should be treated independently with specialised security controls where appropriate.

This approach includes such diverse aspects as risk assessment and modelling; platform security; secure engineering; security management; identity management; sensor integrity; telemetry provenance and PII governance.

TCPS mandate a real-time intrusion-tolerant approach, employing novel heuristics, alternate sensor feeds and self-healing to reduce the impact of compromise.

With TCPS there is an opportunity to address some of the fundamental concerns from the ground up by designing in security at the outset, by developing new protocols and standards that incorporate security and privacy, and by developing systems that tolerate some degree of intrusion without compromising safety.

This shift towards a more proactive and intrusion tolerant security posture could have major benefits in more traditional security contexts such as industrial and enterprise networks.

Risk assessment in TCPS is in its infancy: it is important that we explore how other disciplines such as how ML might be used to offer insights and improve automation in threat and vulnerability analysis (for example, by autogenerating attack trees for critical infrastructure and transportation systems.