Chapter 4: In-Vehicle Communication and Cyber Security

OBJECTIVES

- 4.1 Overview

- 4.2 In-Vehicle System

- 4.3 In-Vehicle Communication

- 4.4 In-Vehicle Network Architecture and Topology

- 4.5 Functional Safety and Cybersecurity

- 4.6 In-Vehicle Cybersecurity Issues and Challenges

- 4.7 Cyber Security in In-Vehicle Network (IVN)

4.1 OVERVIEW

The evolution of intelligent and autonomous vehicles increases the dependence on information sharing among in-vehicle electronic control units (ECUs) and communication within the vehicle, and increases the connection with other vehicles.

As the category of safety equipment is concerned, driver assistance systems for safe driving are experiencing a dramatic growth and development process.

Modern revolutionary advanced driving assistance system (ADAS) functions are made up of dynamic integrated and networked cyber- physical structures.

While the connectivity to the outside world allows many new services, it also exposes the vehicle and its electronics to a possible remote attack.

Hackers with experience of reverse engineering can access the vehicle’s electronic components quickly and in a very short time, resulting in the opening of a new attack surface.

4.2 IN-VEHICLE SYSTEM

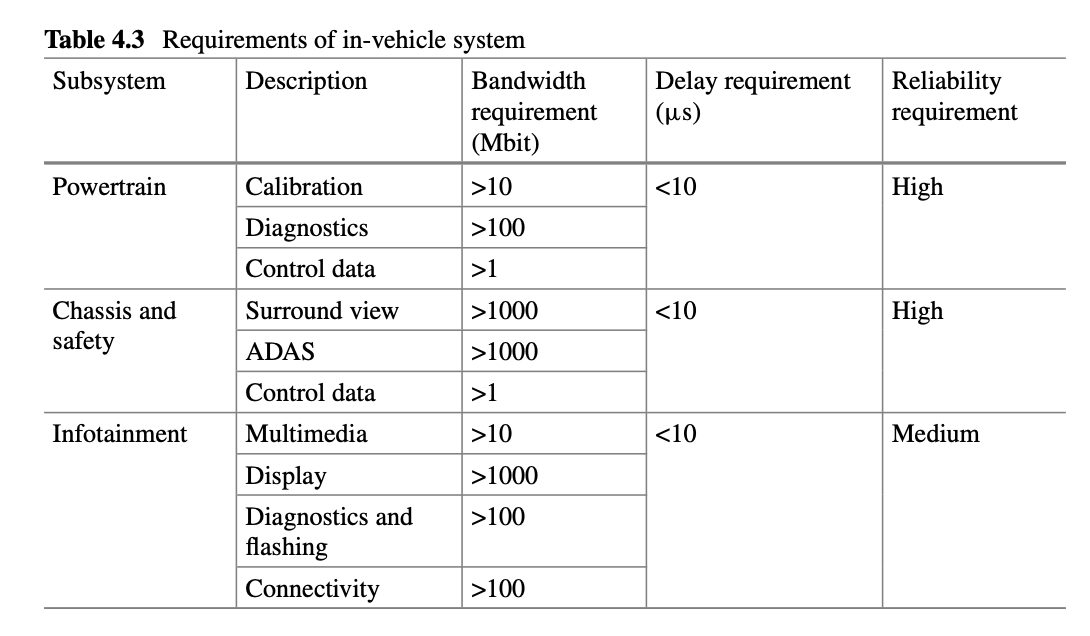

To cope with the demands and requirements of passengers and the drivers, several types of electronic devices and sensors are installed in the vehicle. Currently, the number of such electronic devices for the safety of vehicles to infotainment has increased rapidly and continuously.

Advanced navigation systems and multimedia devices have made their way as mandatory vehicle components so as to make driving more convenient.

Various electronic control units (ECUs) are installed and communicate with other control units, exchanging critical vehicle-related information through in-vehicle LAN communication protocol.

More than 100 embedded ECUs could be integrated in advanced vehicles. The evolution of intelligent and autonomous vehicles increases the dependence on information sharing among in-vehicle ECUs and communication within the vehicle, and increases the connection with other vehicles, resulting in the opening of a new attack surface.

The success of vehicle attack is based on three basic classes: remote attack surface, cyber physical features, and in-vehicle network architecture.

To defend against this, a strong security solution is required in some form.

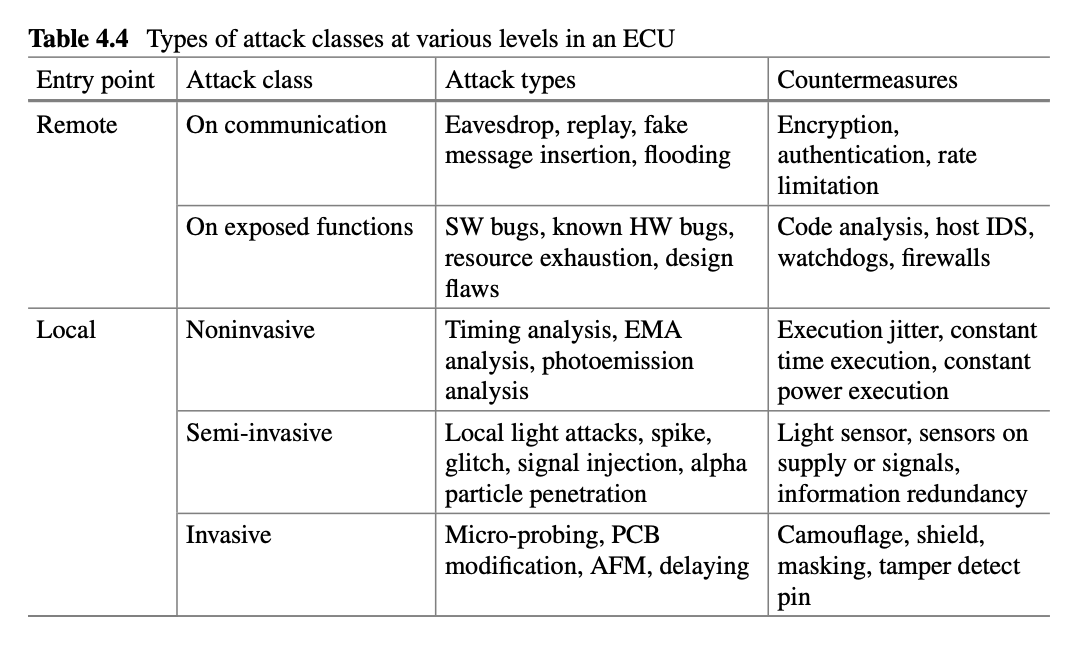

4.2.1 VEHICLE ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONIC SYSTEM

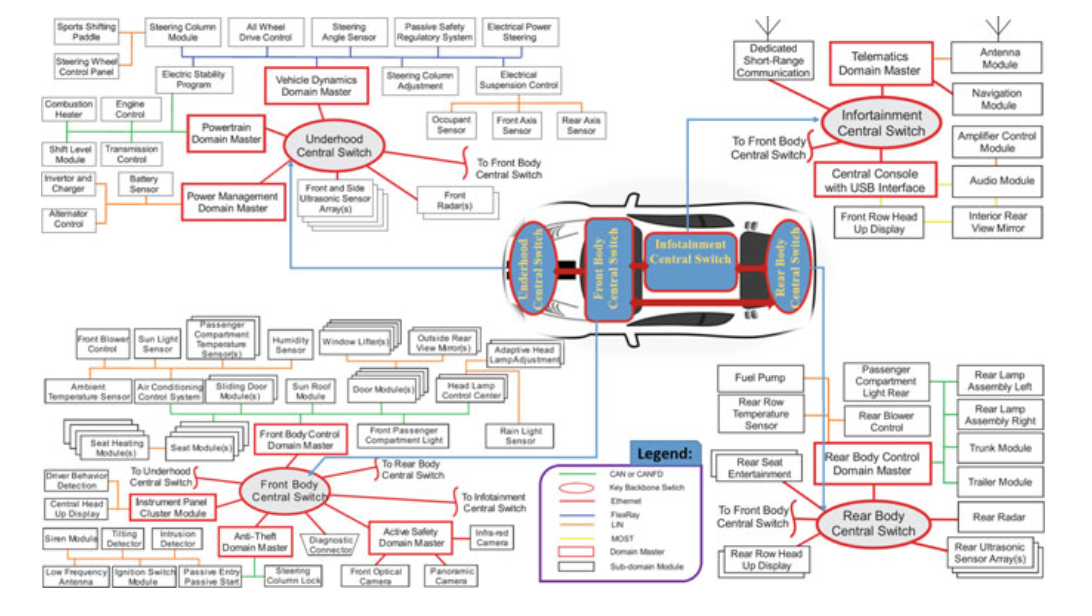

Fig. 4.1 In-vehicle electrical and electronic system

Fig. 4.1 In-vehicle electrical and electronic system

4.3 IN-VEHICLE COMMUNICATION

The in-vehicle communication refers to the intra vehicle communication where all the internal components like telematics, sensors, and actuators communicate with each other using different communication mediums like standard bus system.

The in-vehicle communication occurs within the internal vehicle communication network where the ECUs intercommunicate with other electronic subsystems.

The ECUs are connected within vehicle bus systems through specialized internal communication networks.

Most ECUs are connected to one or more bus networks for monitoring and controlling the vehicles.

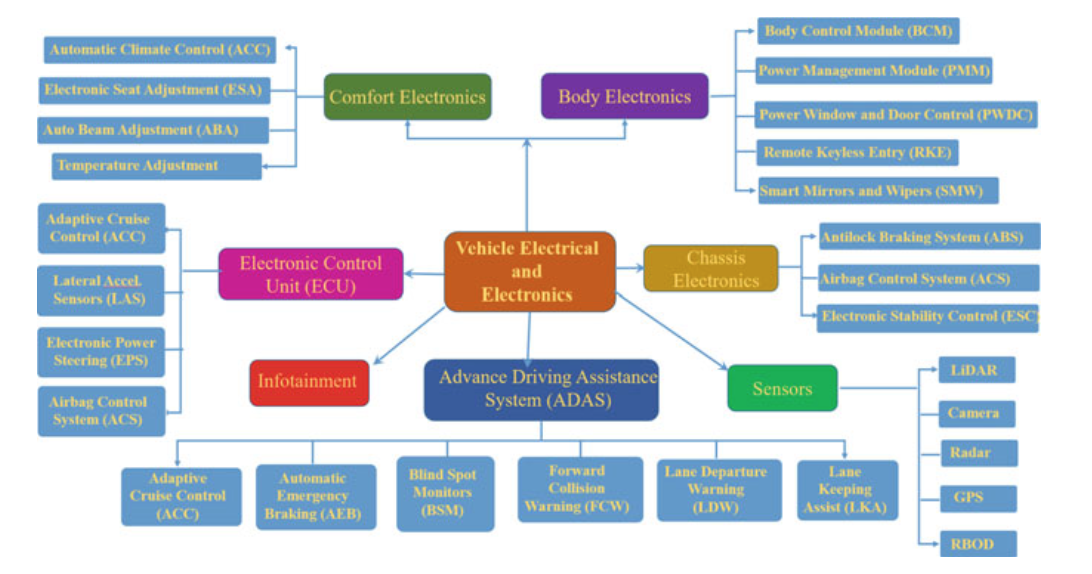

Some ECUs are connected to external controls, such as digital equipment, infotainment, and navigation systems via a gateway system.

The central gateway-based architecture links the entire IVN with a central gateway and provides smooth connectivity between heterogeneous network protocols.

4.3.1 IN-VEHICLE SENSING TECHNOLOGIES

- Sensor Technologies: It includes LiDAR, VLS, ultrasonic ranging device (URD), infrared ranging, and millimeter wave radar (MWR).

- Vision Technologies: It includes stereo vision system (SVS), HD cameras, black box, or CCTVs.

- Positioning Technologies: Some of the positioning technologies are GPS, radar cruise control, and radar-based obstacle detection (RBOD).

Fig. 4.2 Gateway block diagram

4.3.2 IN-VEHICLE NETWORK (IVN) SYSTEMS

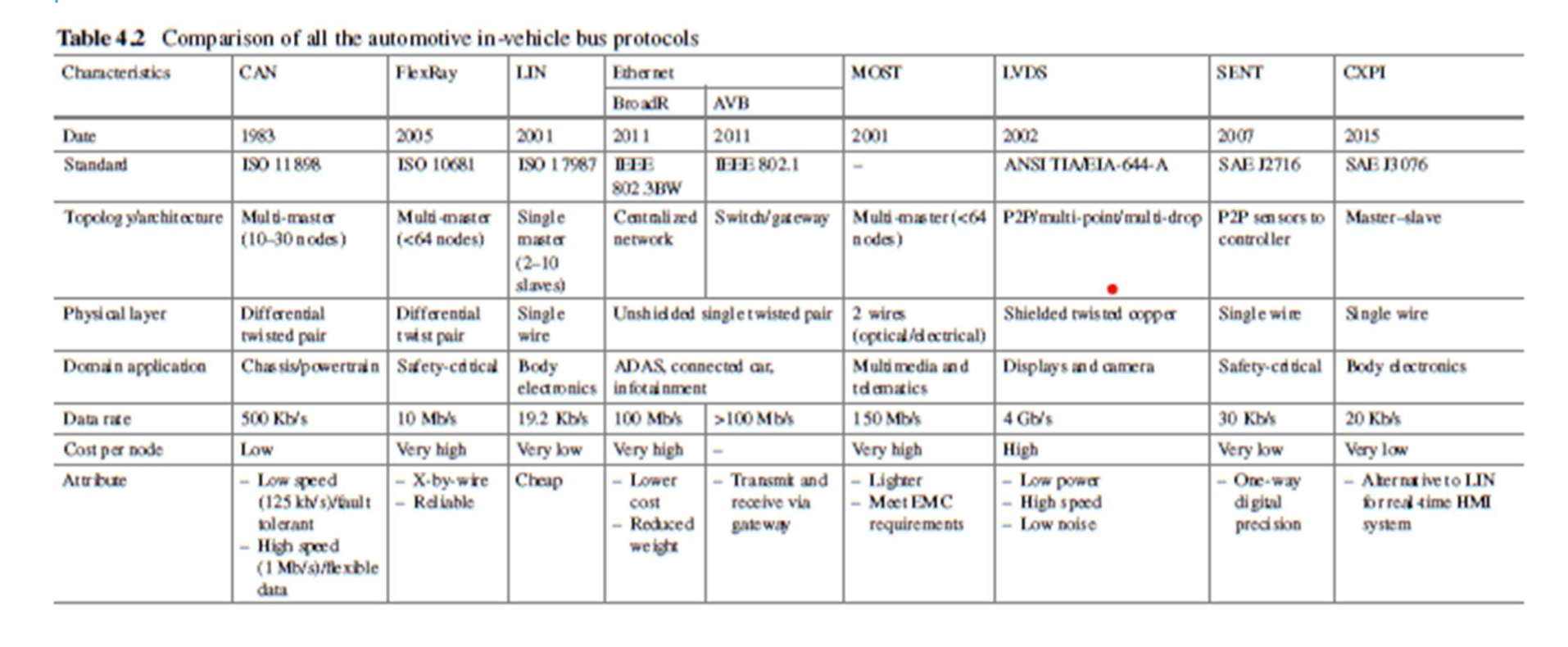

In-Vehicle Networking Types

- FlexRay

- Controller Area Network(CAN)

- Local Interconnect Network (LIN)

- Automotive Ethernet (AE)

- Media Oriented Serial Transport (MOST)

- Single Edge Nibble Transmission (SENT)

Fig. 4.3 In-vehicle networking system [4]

4.4 IN-VEHICLE NETWORK ARCHITECTURE AND TOPOLOGY

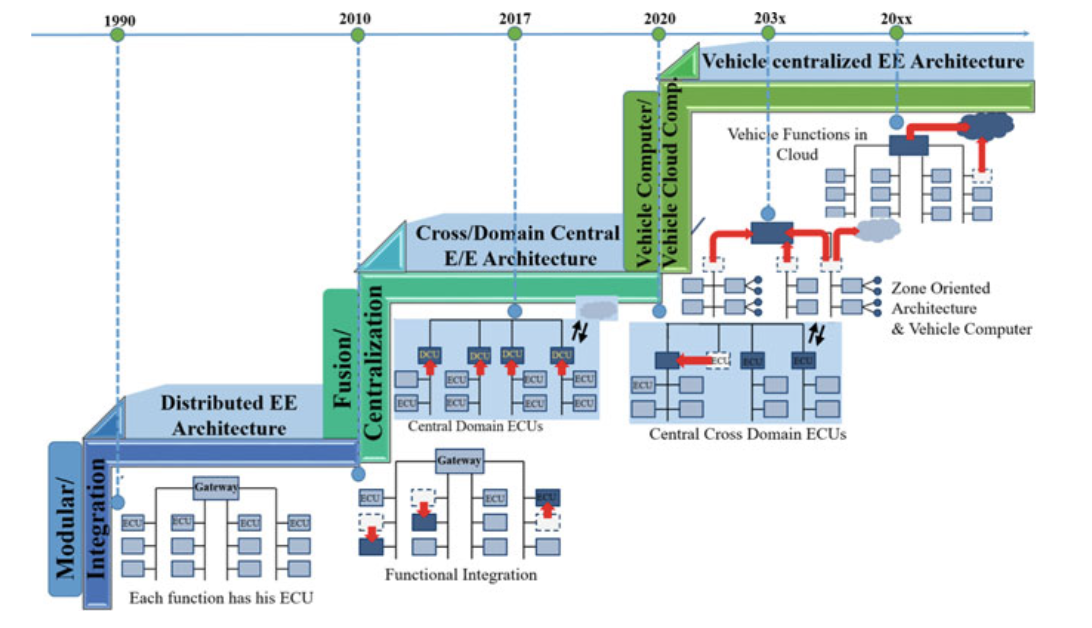

Fig. 4.4 Road map of automotive IVN and future EE architecture

4.5 FUNCTIONAL SAFETY AND CYBERSECURITY

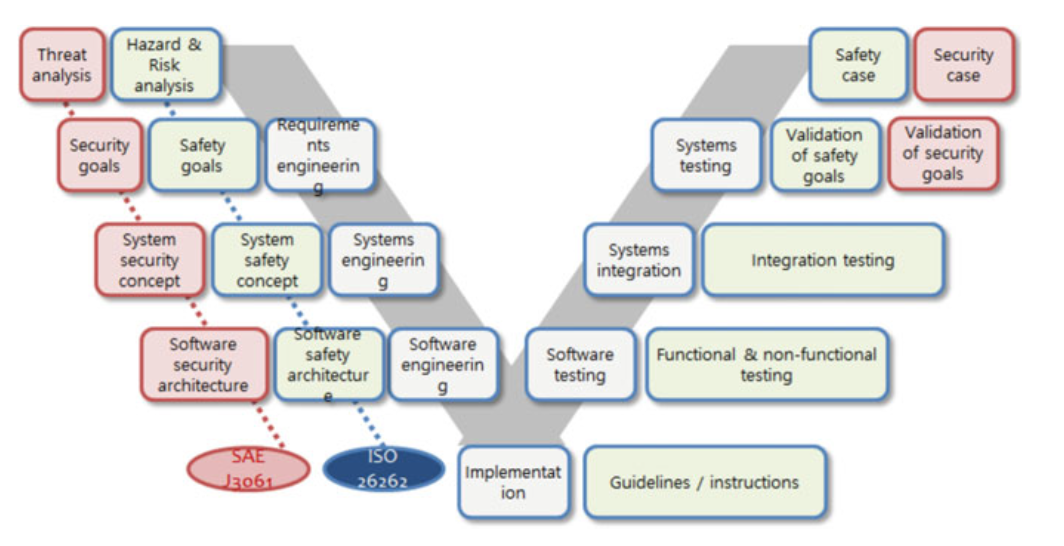

Functional safety is part of a vehicle’s overall safety system or its modules that depends on the cyber physical system (CPS).

It provides safety for its modules so that the modules function correctly in response to the inputs, including secure maintenance, equipment faults, etc.

The functional safety is defined by ISO 26262 and IEC 61508 for hazard and risk analysis (HARA), safety engineering, functional and risk management.

The vehicle security is defined by security standards such as ISO 27001, ISO 15408, ISO 214534, and SAE J3061 for threat and risk analysis (TARA), security engineering, and misuse cases.

Functional safety can be accomplished when each specified safety task is performed and the performance level needed for each safety function is met.

This is usually done by a method that involves steps such as (i) safety function identification, (ii) safety function assessment, (iii) safety function verification, (iv) failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA), and (v) functional safety audits activity.

One of the safety concerns in autonomous vehicle is that human-in-loop activities cause risks that can lead to failures and disasters, when appropriate safety mechanisms are not properly implemented.

Fig. 4.5 Interaction between functional safety and cybersecurity [14]

4.6 IN-VEHICLE CYBERSECURITY ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

4.6.1 Challenges of IVN Architecture

4.6.2 IN-VEHICLE ONBOARD PORTS, THREATS, AND COUNTERMEASURES

There are a number of ports inside modern vehicles that, when linked to external devices, allow users to access services and infotainment information.

The 3 vehicle ports are: onboard diagnostics (OBD)-II ports, the USB ports, and electric vehicle charging ports.

Such ports synchronize user’s smartphones and recharge their electric cars.

But, if hackers obtain access to such ports, they might get access to the in-vehicle system, execute eavesdropping attacks, and perhaps even install malware and ransomware.

Such interfaces allow external inputs from which core ECUs can be exploited remotely by software bugs, remote control of a car over the Internet, among others.

Countermeasures to Port Threats:

- In IVN, the OBD-II threats can be overcome by tracking the frame injection coming from the OBD-II port as well as encrypting and signing the message for firmware updates.

- Due to the large application of USB devices, it poses security vulnerabilities so a standard USB security should be developed to protect against the cyber-attacks.

- The threats to USB port can be prevented in two ways; first, the USB that connects to the Internet should require a security certificate, which may then permit it to link to the vehicle, and secondly, preventing the access of malware or viruses to enter the sensitive security area via the USB port.

- To prevent the EV charging port attack, authentication schemes, cryptographic signatures, and secure firmware updates should be used to prevent the various attacks during charging.

- In addition, Open Charging Point Protocol (OCPP)-based secure charging system in smart grid can be used to secure the EV charging systems.

4.7 CYBER SECURITY IN IN-VEHICLE NETWORK (IVN)

4.7.1 In-Vehicle Network (IVN) Security Threats

- CAN Security Threats: CAN bus system is vulnerable to different types of attacks such as injection, masquerading, denial of service (DoS), eavesdropping, replay, and bus-off attacks.

- Masquerading attacks occur in CAN because the CAN frames are not encrypted.

- For countermeasures against attacks such as masquerading, eavesdropping, injection, and replay attacks, the messages exchanged between ECUs could be encrypted and authenticated or by transmitting a fraction of MAC in each frame such that the tampering recognition can be carried out for all separate frames.

- FlexRay Security Threats: In FlexRay, the most common types of threats are eavesdropping attacks and static segment attacks. In case of eavesdropping attacks, the attackers gain access to the FlexRay messages and obtain all the information.

- It causes data leakages, affects data confidentiality, and concerns security primitives.

- The static segment attacks include masquerading, injection, and replay attacks, and the attackers attack the static segment of the FlexRay communication cycle.

- The countermeasure for both the static segment attacks and the eavesdropping attacks is by implementing message authentication within the static segment via hardware coprocessor, where feasible.

- LIN Security Threats: LIN is commonly used along with CANs and is therefore prone to unwanted access through theCANbus.

- Some of the attacks to LIN are response collision, message spoofing, and header collision attacks.

- During a collision response attack, an attacker concurrently transmits an illicit message with false header along with a valid message to exploit LIN’s error handling protocol.

- The countermeasure for these types of attacks is to send unusual signals by the slave node so that it will overwrite the attacker’s fake messages, when the bus value mismatches its response.

- AE Security Threats: The threats to AE security are traffic integrity attacks, network access attacks, DoS attacks, and traffic confidentiality attacks.

- In case of network access attacks, the attacker connects to the Ethernet network by connecting to the unsecured port of the switch, gains access to the network, takes control of other nodes or switches, or remotely accesses to the Ethernet network.

- The countermeasures to these types of attacks are authentication approach and frame replication method that eliminate traffic confidentiality and traffic integrity attack.

- The network access attack can be countermeasured by virtual local area network segmentation.

- MOST Security Threats: There are two common types of attacks in MOST, and they are synchronization disruption attacks and jamming attacks.

- In synchronization disruption attacks, the attacker sends the fake timing frames to tamper the synchronization of MOST.

- In jamming attacks, the jammer repeatedly delivers misleading messages to interrupt legitimate low-priority specified-length messages or constantly requesting data channels on MOST transmission through control channels.

- The countermeasures on MOST security can be achieved by authenticating the source nodes, encrypting the exchanged messages, and implementing firewalls and gateway.

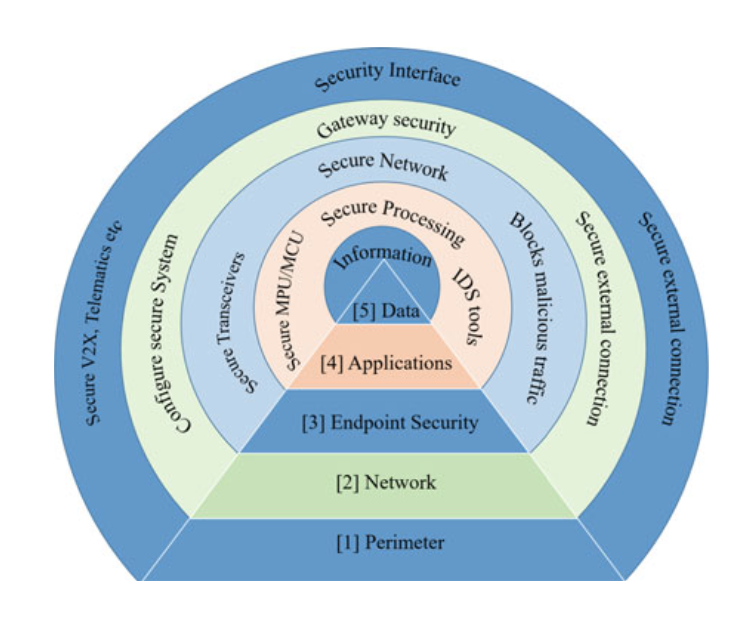

4.7.2 CYBERSECURITY PROTECTION LAYERS

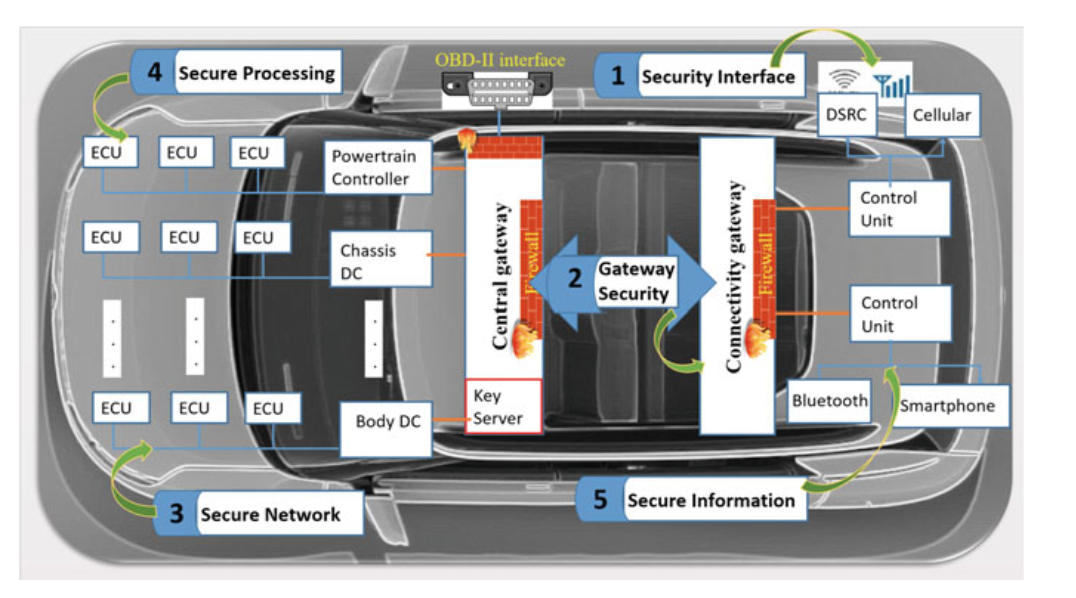

Fig. 4.6 Cybersecurity protection layers for autonomous vehicles

Fig. 4.7 In-vehicle cybersecurity protection layers

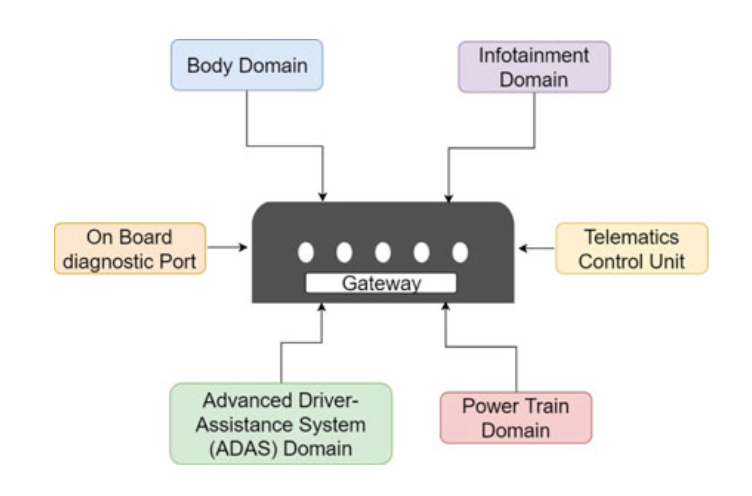

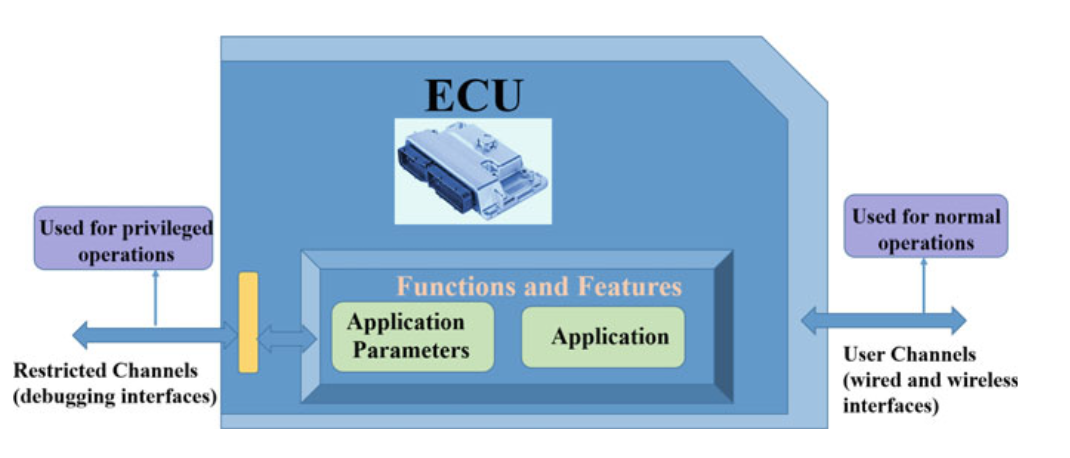

4.7.3 CYBERSECURITY FOR ECU

Fig. 4.8 ECU channels and interfaces