Networked Applications

Other than simple end-user tools on a business workstation, business applications are rarely installed and used within the context of an individual computer. Instead, many applications are centrally installed and used by many people who are often in many locations. Data networks facilitate the communications between central servers and business workstations. The applications discussed in the following sections are client-server, web-based, and middleware.

Client-Server

Client-server applications are a prior-generation technology used to build high-performance business applications. They consist of one or more central application servers, database servers, and business workstations. The central application servers contain some business logic—primarily the instructions to receive and respond to requests sent from workstations. The remainder of the business logic will reside on each business workstation; primarily this is the logic used to display and process forms and reports for the user.

When a user is using a client-server application, he or she is typically selecting functions to input, view, or change information. When information is input, application logic on the business workstation will request, analyze, and accept the information and then transmit it to the central application server for further processing and storage. When viewing information, a user will typically select a viewing function with, perhaps, criteria specifying which information they want to view. Business logic on the workstation will validate this information and then send a request to the central application server, which in turn will respond with information that is then sent back to the workstation and transformed for easy viewing.

The promise of client-server applications was improved performance by removing all application display logic from the central computer and placing that logic on each individual workstation. This scheme succeeded in principle but failed in practice for two principal reasons:

- Network performance

Client-server applications often overburdened the organization’s data network, and application performance failed when many people were using it at once. A typical example is a database query issued by a workstation that results in thousands of records being returned to the workstation over the network. - Workstation software updates

Keeping the central application software and the software modules on each workstation in sync proved to be problematic. Often, updates required that all workstations be upgraded at the same time. Invariably, some workstations are down or otherwise unavailable for updates (powered down by end users or taken home if they are laptop computers), potentially resulting in application malfunctions for those users.

Organizations that did implement full-scale client-server applications were often dissatisfied with the results. And at nearly the same time, the World Wide Web was invented and soon proved to be a promising, simpler alternative.

Client-server application design has enjoyed a revival with the advent of smartphone and tablet applications, or apps, which are often designed as client-server.

Web-Based Applications

With client-server applications declining in favor, web-based applications were the only way forward. The primary characteristics of web-based applications that make them highly favorable include

- Centralized business logic

All business logic resides on one or more centralized servers. There are no longer issues related to pushing software updates to workstations since they run web browsers that rarely require updating. - Lightweight and universal display logic

Display logic, such as forms, lists, and other application controls, is easily written in HTML, a simple markup language that displays well on workstations without any application logic on the workstation. - Lightweight network requirements

Unlike client-server applications that would often send large amounts of data from the centralized server to the workstation, web applications send mainly display data to workstations. - Workstations requiring few, if any, updates

Workstations require only browser software. Updates to applications themselves are entirely server-based. - Fewer compatibility issues

Instead of requiring a narrow choice of workstations, web-based applications can run on nearly every kind of workstation, including Unix, Windows, macOS, Chrome OS, or Linux.

Middleware

Middleware is a component used in some client-server or web-based application environments to control the processing of communications or transactions. Middleware manages the interaction between major components in larger application environments.

Some of the common types of middleware include

- Transaction processing (TP) monitors

A TP monitor manages transactions between application servers and database servers to ensure the integrity of business transactions among a collection of database servers. - RPC gateways

These systems facilitate communications through the suite of RPC protocols between various components of an application environment. - Object request broker (ORB) gateways

An ORB gateway facilitates the execution of transactions across complex, multiserver application environments that use CORBA (Common Object Request Broker Architecture) or Microsoft COM/DCOM technologies. - Message servers

These systems store and forward transactions between systems and ensure the eventual delivery of transactions to the right systems.

Middleware is typically used in a large, complex application environment, particularly when there are multiple technologies (operating systems, databases, and languages) in use. Middleware can be thought of as glue that helps the application environment operate more smoothly.

Business Resilience

In the context of information systems, business resilience is concerned with the resilience of IT systems and business applications that support critical business processes, to ensure the ongoing viability of the organization as well as survival in the event of a major disaster. Given the phenomenon of digital transformation (DX), which represents an increasing dependency of business processes on information technology, ensuring the resilience of IT systems is all the more important. The two primary activities within business resilience are business continuity planning and disaster recovery planning.

Business Continuity Planning

Business continuity planning (BCP) is a business activity that is undertaken to reduce risks related to the onset of disasters and other disruptive events. BCP activities identify the most critical activities and assets in an organization. They identify risks and mitigate those risks through changes or enhancements in technology or business processes so that the impact of disasters is reduced and the time to recovery is lessened. The primary objective of BCP is to improve the chances that the organization will survive a disaster without incurring costly or even fatal damage to its most critical activities.

The activities of BCP development scale for any size organization. BCP has the unfortunate reputation of existing only in the stratospheric, thin air of the largest and wealthiest organizations. This misunderstanding hurts the majority of organizations that are too timid to begin any kind of BCP effort at all because they believe that these activities are too costly and disruptive. The fact is that any size organization, from a one-person home office to a multinational conglomerate, can successfully undertake BCP projects that will bring about immediate benefits as well as take some of the sting out of disruptive events that do occur.

Organizations can benefit from BCP projects, even if a disaster never occurs. The steps in the BCP development process usually bring immediate benefit in the form of process and technology improvements that increase the resilience, integrity, and efficiency of those processes and systems.

EXAM TIP

Business continuity planning is closely related to disaster recovery planning—both are concerned with the recovery of business operations after a disaster.

Disasters

I always tried to turn every disaster into an opportunity.

*–*John D. Rockefeller

In a business context, disasters are unexpected and unplanned events that result in the disruption of business operations. A disaster could be a regional event spread over a wide geographic area, or it could occur within the confines of a single room. The impact of a disaster will also vary, from a complete interruption of all company operations to a mere slowdown. (The question invariably comes up: when is a disaster a disaster? This is somewhat subjective, like asking, “When is a person sick?” Is it when he or she is too ill to report to work, or if he or she just has a sniffle and a scratchy throat? I’ll discuss disaster declaration later in this chapter.)

Types of Disasters

BCP professionals broadly classify disasters as natural or human-made, although the origin of a disaster does not figure very much into how we respond to it. Let’s examine the types of disasters.

Natural Disasters

Natural disasters are phenomena that occur in the natural world with little or no assistance from mankind. They are a result of the natural processes that occur in, on, and above the earth.

Examples of natural disasters include

- Earthquakes

Sudden movements of the earth with the capacity to damage buildings, houses, roads, bridges, and dams; to precipitate landslides and avalanches; and to induce flooding and other secondary events. - Volcanoes

Eruptions of magma, pyroclastic flows, steam, ash, and flying rocks that can cause significant damage over wide geographic regions. Some volcanoes, such as Kilauea in Hawaii, produce a nearly continuous and predictable outpouring of lava in a limited area, whereas others, such as the Mount St. Helens eruption in 1980 in Washington state, caused an ash fall over thousands of square miles that brought many metropolitan areas to a standstill for days and also blocked rivers and damaged roads. Figure 5-23 shows a volcanic eruption as seen from space.

Figure 5-23 Mount Etna volcano in Sicily

- Landslides

Sudden downhill movements of earth, usually down steep slopes, can bury buildings, houses, roads, and public utilities and cause secondary (although still disastrous) effects such as the rerouting of rivers. - Avalanches

Sudden downward flows of snow, rocks, and debris on a mountainside can damage buildings, houses, roads, and utilities, resulting in direct or indirect damage affecting businesses. A slab avalanche consists of the movement of a large, stiff layer of compacted snow. A loose snow avalanche occurs when the accumulated snowpack exceeds its shear strength. A power snow avalanche is the largest type and can travel in excess of 200 mph and exceed 10 million tons of material. - Wildfires

Fires in forests, chaparral, and grasslands are part of the natural order. However, fires can also damage power lines, buildings, equipment, homes, and entire communities, and cause injury and death. - Tropical cyclones

The largest and most violent storms are known in various parts of the world as hurricanes, typhoons, tropical cyclones, tropical storms, and cyclones. Tropical cyclones consist of strong winds that can reach 190 mph, heavy rains, and storm surge that can raise the level of the ocean by as much as 20 feet, all of which can result in widespread coastal flooding and damage to buildings, houses, roads, and utilities and significant loss of life. - Tornadoes

These violent rotating columns of air can cause catastrophic damage to buildings, houses, roads, and utilities when they reach the ground. Most tornadoes can have wind speeds from 40 to 110 mph and travel along the ground for a few miles. Some tornadoes can exceed 300 mph and travel for dozens of miles. - Windstorms

While generally less intense than hurricanes and tornadoes, windstorms can nonetheless cause widespread damage, including damage to buildings, roads, and utilities. Widespread electric power outages are common, as windstorms can uproot trees that can fall into overhead power lines. - Lightning

Atmospheric discharges of electricity occur during thunderstorms, but also during dust storms and volcanic eruptions. Lightning can start fires and also damage buildings and power transmission systems, causing power outages. - Ice storms

Ice storms occur when rain falls through a layer of colder air, causing raindrops to freeze onto whatever surface they strike. They can cause widespread power outages when ice forms on power lines and the resulting weight causes those power lines to collapse. A notable example is the Great Ice Storm of 1998 in eastern Canada, which resulted in millions being without power for as long as two weeks and in the virtual immobilization of the cities of Montreal and Ottawa. - Hail

This form of precipitation consists of ice chunks ranging from 5mm to 150mm in diameter. An example of a damaging hailstorm is the April 1999 storm in Sydney, Australia, where hailstones up to 9.5cm in diameter damaged 40,000 vehicles, 20,000 properties, and 25 airplanes, and caused one direct fatality. The storm caused $1.5 billion in damage. - Flooding

Standing or moving water spills out of its banks and flows into and through buildings and causes significant damage to roads, buildings, and utilities. Flooding can be a result of locally heavy rains, heavy snowmelt, a dam or levee break, tropical cyclone storm surge, or an avalanche or landslide that displaces lake or river water. - Tsunamis

This series of waves usually results from the sudden vertical displacement of a lake bed or ocean floor, but a tsunami can also be caused by landslides, asteroids, or explosions. A tsunami wave can be barely noticeable in open, deep water, but as it approaches a shoreline, the wave can grow to a height of 50 feet or more. Recent notable examples are the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2011 Japan tsunami. Coastline damage from the Japan tsunami is shown in Figure 5-24.

Figure 5-24 Damage to structures caused by the 2011 Japan tsunami

- Pandemic

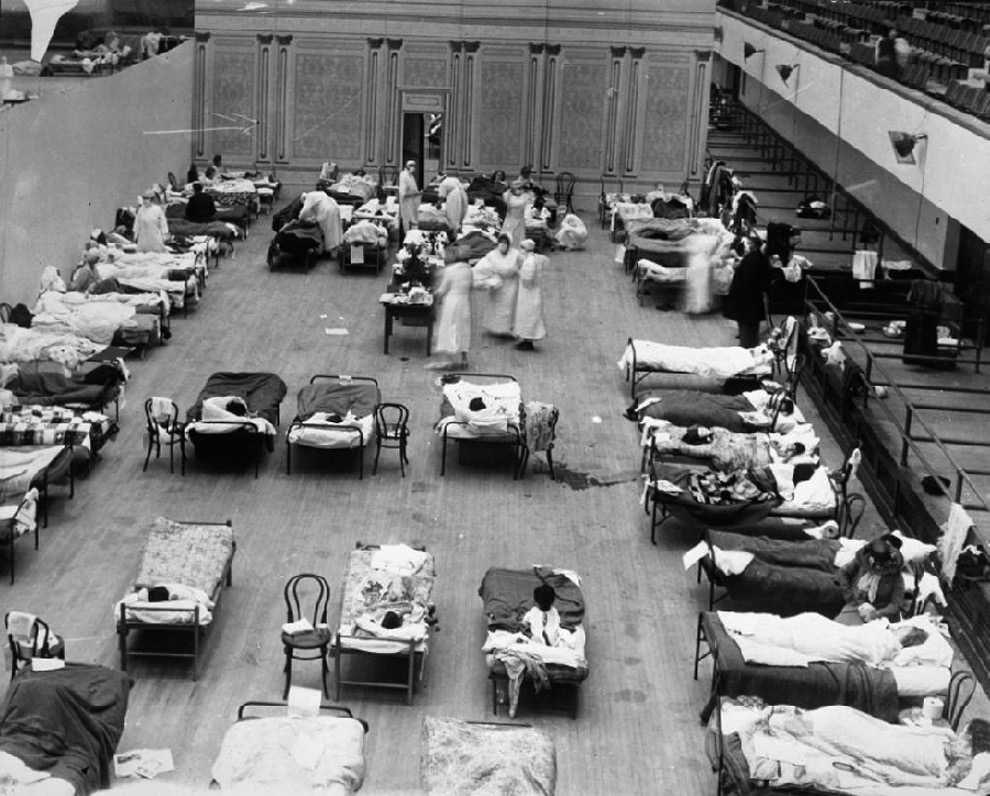

The spread of infectious disease can occur over a wide geographic region, even worldwide. Pandemics have regularly occurred throughout history and are likely to continue occurring, despite advances in sanitation and immunology. A pandemic is the rapid spread of any type of disease, including typhoid, tuberculosis, bubonic plague, or influenza. Pandemics in the 20th century include the 1918–1920 Spanish flu, the 1956–1958 Asian flu, the 1968–1969 Hong Kong “swine” flu, and the 2009–2010 swine flu pandemics. Figure 5-25 shows an auditorium that was converted into a hospital during the 1918–1920 pandemic.

Figure 5-25 An auditorium was used as a temporary hospital during the 1918 flu pandemic.

Extraterrestrial impacts

This category includes meteorites and other objects that may fall from the sky from way, way up. Sure, these events are extremely rare, and most organizations don’t even include these events in their risk analysis, but I’ve included it here for the sake of rounding out the types of natural events.

Human-Made Disasters

Human-made disasters are events that are directly or indirectly caused by human activity through action or inaction. The results of human-made disasters are similar to natural disasters: localized or widespread damage to businesses that results in potentially lengthy interruptions in operations.

Examples of human-made disasters include

- Civil disturbances

These can include protests, demonstrations, riots, strikes, work slowdowns and stoppages, looting, and resulting actions such as curfews, evacuations, or lockdowns. - Utility outages

Failures in electric, natural gas, district heating, water, communications, and other utilities can be caused by equipment failures, sabotage, or natural events such as landslides or flooding. - Service outages

Failures in IT equipment, software programs, and online services can be caused by hardware failures, software bugs, or misconfiguration. - Materials shortages

Interruptions in the supply of food, fuel, supplies, and materials can have a ripple effect on businesses and the services that support them. Readers who are old enough to remember the petroleum shortages of the mid-1970s know what this is all about; Figure 5-26 shows a line at a gas station during a 1970s-era gasoline shortage. Shortages can result in spikes in the price of commodities, which is almost as damaging as not having any supply at all.

Figure 5-26 Citizens wait in long lines to buy fuel during a gas shortage.

- Fires

As contrasted to wildfires, human-made fires originate in or involve homes, buildings, equipment, and materials. - Hazardous materials spillsMany created or refined substances can be dangerous if they escape their confines. Examples include petroleum substances, gases, pesticides and herbicides, medical substances, and radioactive substances.

- Transportation accidents

This broad category includes plane crashes, railroad derailments, bridge collapses, and the like. - Terrorism and war

Whether they are actions of a nation, nation-state, or group, terrorism and war can have devastating but usually localized effects in cities and regions. Often, terrorism and war precipitate secondary effects such as materials shortages and utility outages. - Security events

The actions of a lone hacker or a team of organized cyber-criminals can bring down one system, one network, or many networks, which could result in widespread interruption in services. The hackers’ activities can directly result in an outage, or an organization can voluntarily (although reluctantly) shut down an affected service or network to contain the incident.

NOTE

It is important to remember that real disasters are usually complex events that involve more than just one type of damaging event. For instance, an earthquake directly damages buildings and equipment, but it can also cause fires and utility outages. A hurricane also brings flooding, utility outages, and sometimes even hazardous materials events and civil disturbances such as looting.

- How Disasters Affect Organizations

Disasters have a wide variety of effects on an organization. Many disasters have direct effects, but sometimes it is the secondary effects of a disaster event that are most significant from the perspective of ongoing business operations.

A risk analysis is a part of the BCP process (discussed in the next section) that will identify the ways in which disasters are likely to affect a particular organization. During the risk analysis, the primary, secondary, and downstream effects of likely disaster scenarios need to be identified and considered. Whoever is performing this risk analysis will need to have a broad understanding of the interdependencies of business processes and IT systems, as well as the ways in which a disaster will affect ongoing business operations. Similarly, personnel who are developing contingency and recovery plans also need to be familiar with these effects so that those plans will adequately serve the organization’s needs.

Disasters, by our definition, interrupt business operations in some measurable way. An event that has the appearance of a disaster may occur, but if it doesn’t affect a particular organization, then we would say that no disaster occurred, at least for that particular organization.

It would be shortsighted to say that a disaster affects only operations. Rather, it is appropriate to understand the longer term effects that a disaster has on the organization’s image, brand, reputation, and ongoing financial viability. The factors affecting image, brand, and reputation have as much to do with how the organization communicates to its customers, suppliers, and shareholders as with how the organization actually handles a disaster in progress.

Some of the ways that a disaster affects an organization’s operations include

- Direct damage

Events such as earthquakes, floods, and fires directly damage an organization’s buildings, equipment, or records. The damage may be severe enough that no salvageable items remain, or it may be less severe, where some equipment and buildings may be salvageable or repairable. - Utility interruption

Even if an organization’s buildings and equipment are undamaged, a disaster may affect utilities such as power, natural gas, or water, which can incapacitate some or all business operations. Significant delays in refuse collection can result in unsanitary conditions. - Transportation

A disaster may damage or render transportation systems such as roads, railroads, shipping, or air transport unusable for a period. Damaged transportation systems will interrupt supply lines and personnel. - Services and supplier shortageEven if a disaster does not have a direct effect on an organization, critical suppliers affected by a disaster can have an undesirable effect on business operations. For instance, a regional baker that cannot produce and ship bread to its corporate customers will soon result in sandwich shops and restaurants without a critical resource.

- Staff availability

A community-wide or regional disaster that affects businesses is also likely to affect homes and families. Depending upon the nature of a disaster, employees will place a higher priority on the safety and comfort of family members. Also, workers may not be able or willing to travel to work if transportation systems are affected or if there is a significant materials shortage. Employees may also be unwilling to travel to work if they fear for their personal safety or that of their families. - Customer availability

Various types of disasters may force or dissuade customers from traveling to business locations to conduct business. Many of the factors that keep employees away may also keep customers away.

CAUTION

The kinds of secondary and tertiary effects that a disaster has on a particular organization depend entirely upon its unique set of circumstances that constitute its specific critical needs. A risk analysis should be performed to identify these specific factors.

The Business Continuity Planning Process

The proper way to plan for disaster preparedness is first to know what kinds of disasters are likely and their possible effects on the organization. That is, plan first, act later.

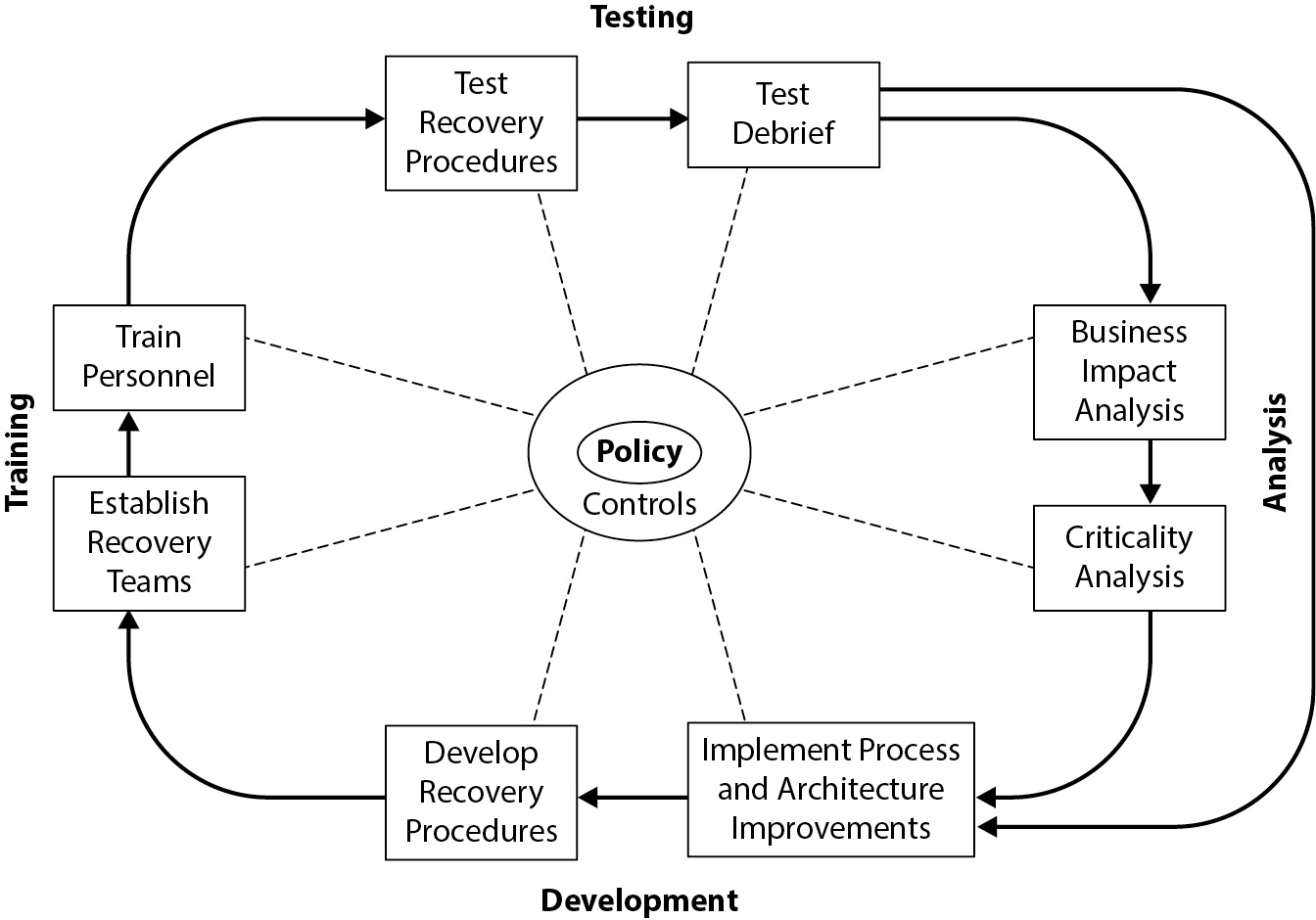

The business continuity planning process is a life cycle process. In other words, business continuity planning (and disaster recovery planning) is not a one-time event or activity. It’s a set of activities that results in the ongoing preparedness for disaster that continually adapts to changing business conditions and that continually improves.

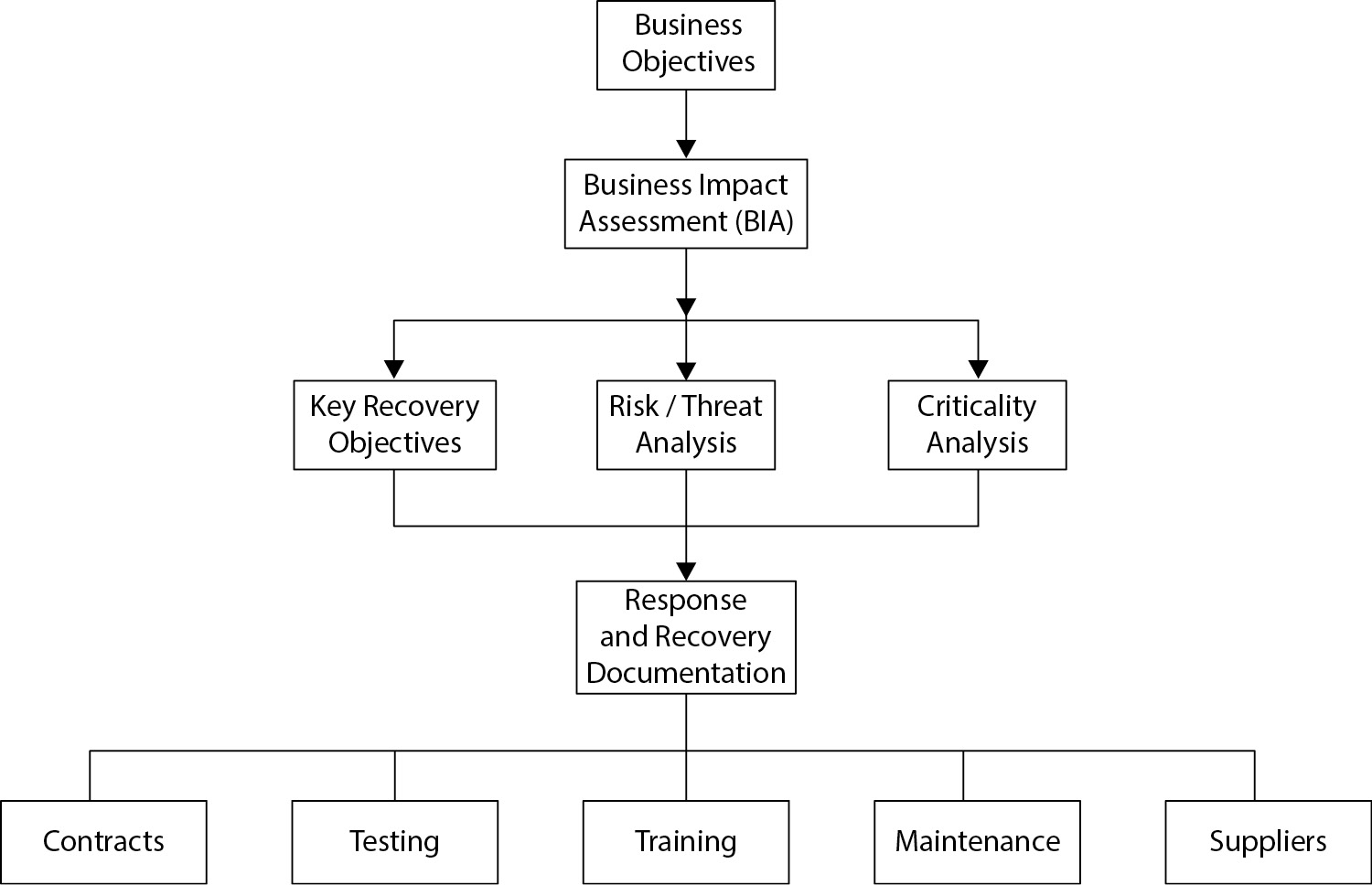

The elements of the BCP process life cycle are

- Develop BCP policy.

- Conduct business impact analysis (BIA).

- Perform criticality analysis.

- Establish recovery targets.

- Develop recovery and continuity strategies and plans.

- Test recovery and continuity plans and procedures.

- Train personnel.

- Maintain strategies, plans, and procedures through periodic reviews and updates.

The BCP life cycle is shown in Figure 5-27. The details of this life cycle are described in detail in this chapter.

Figure 5-27 The BCP process life cycle

BCP Policy

A formal BCP effort must, like any strategic activity, flow from the existence of a formal policy and be included in the overall governance model that is the topic of this chapter. BCP should be an integral part of the IT control framework; it should not lie outside of it. Therefore, BCP policy should include or cite specific controls that ensure that key activities in the BCP life cycle are performed appropriately.

BCP policy should also define the scope of the BCP strategy. This means that the specific business processes (or departments or divisions within an organization) that are included in the BCP effort must be defined. Sometimes the scope will include a geographic boundary. In larger organizations, it is possible to “bite off more than you can chew” and define too large a scope for a BCP project, so limiting scope to a smaller, more manageable portion of the organization can be a good approach.

BCP and COBIT Controls

The specific COBIT controls that are involved with BCP are contained within DSS04—Ensure continuous service. DSS04 has eight specific controls that constitute the entire BCP life cycle:

- Define the business continuity policy, objectives and scope.

- Maintain a continuity strategy.

- Develop and implement a business continuity response.

- Exercise, test and review the BCP.

- Review, maintain and improve the continuity plan.

- Conduct continuity plan training.

- Manage backup arrangements.

- Conduct post-resumption review.

These controls are discussed in this chapter and also in COBIT.

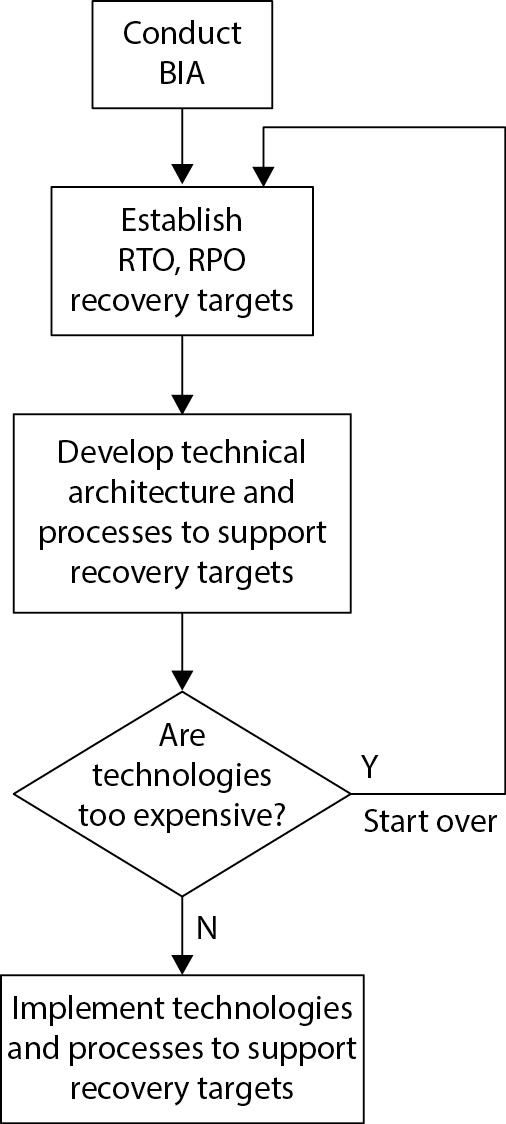

Business Impact Analysis

The objective of the business impact analysis (BIA) is to identify the impact that different scenarios will have on ongoing business operations. The BIA is one of several steps of critical, detailed analysis that must be carried out before the development of continuity or recovery plans and procedures.

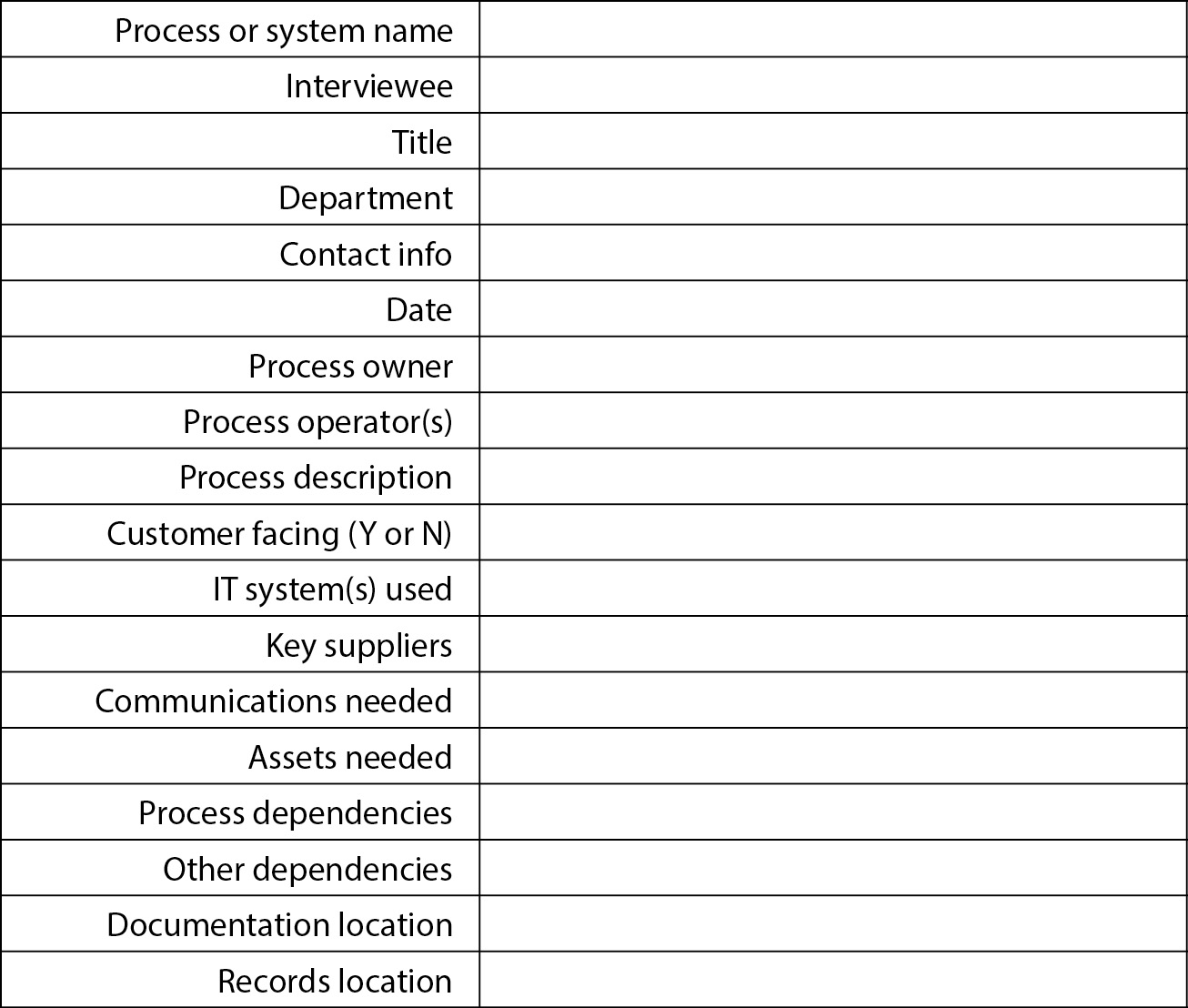

Inventory Key Processes and Systems

The first step in a BIA is the collection of key business processes and IT systems. Within the overall scope of the BCP project, the objective here is to establish a detailed list of all identifiable processes and systems. The usual approach is the development of a questionnaire or intake form that would be circulated to key personnel in end-user departments and also within IT. A sample intake form is shown in Figure 5-28.

Figure 5-28 BIA sample intake form for gathering data about key processes

Typically, the information that is gathered on intake forms is transferred to a multi-columned spreadsheet, where information on all of the organization’s in-scope processes can be viewed together. This will become even more useful in subsequent phases of the BCP project, such as the criticality analysis.

TIP

Use of an intake form is not the only accepted approach when gathering information about critical processes and systems. It’s also acceptable to conduct one-on-one interviews or group interviews with key users and IT personnel to identify critical processes and systems. I recommend the use of an intake form (whether paper-based or electronic), even if the interviewer uses it only as a framework for note-taking.

Planning Precedes Action

IT personnel are often eager to get to the fun and meaty parts of a project. Developers are anxious to begin coding before design; system administrators are eager to build systems before they are scoped and designed; and BCP personnel fervently desire to begin designing more robust system architectures and to tinker with replication and backup capabilities before key facts are known. In the case of business continuity and disaster recovery planning, completion of the BIA and other analyses is critical, as the analyses help to define the systems and processes most needed before getting to the fun part.

Statements of Impact

When processes and systems are being inventoried and cataloged, it is also vitally important to obtain one or more statements of impact for each process and system. A statement of impact is a qualitative or quantitative description of the impact on the business if the process or system were incapacitated for a time.

For IT systems, you might capture the number of users and the names of departments or functions that are affected by the unavailability of a specific IT system. Include the geography of affected users and functions if that is appropriate. Here are some example statements of impact for IT systems:

- Three thousand customer support users in France and Italy will be unable to access customer records.

- All users in North America will be unable to read or send e-mail. Statements of impact for business processes may cite the business functions that would be affected. Here are some examples:

- Accounts payable and accounts receivable functions will be unable to process.

- Legal department will be unable to access contracts and addendums.

Statements of impact for revenue-generating and revenue-supporting business functions could quantify financial impact per unit of time (be sure to use the same units of time for all functions so that they can be easily compared with one another). Here are some examples:

- Inability to place orders for appliances will cost at the rate of $12,000 per hour.

- Delays in payments will cost $45,000 per day in interest charges. As statements of impact are gathered, it may make sense to create several columns in the main worksheet so that like units (names of functions, numbers of users, financial figures) can be sorted and ranked later on.

A complete BIA will have the following information about each process and system:

- Name of the system or process

- Who is responsible for it

- A description of its function

- Dependencies on systems

- Dependencies on suppliers

- Dependencies on key employees

- Quantified statements of impact in terms of revenue, users affected, and/or functions impacted

You’re almost home.

Criticality Analysis When all of the BIA information has been collected and charted, the criticality analysis (CA) can be performed.

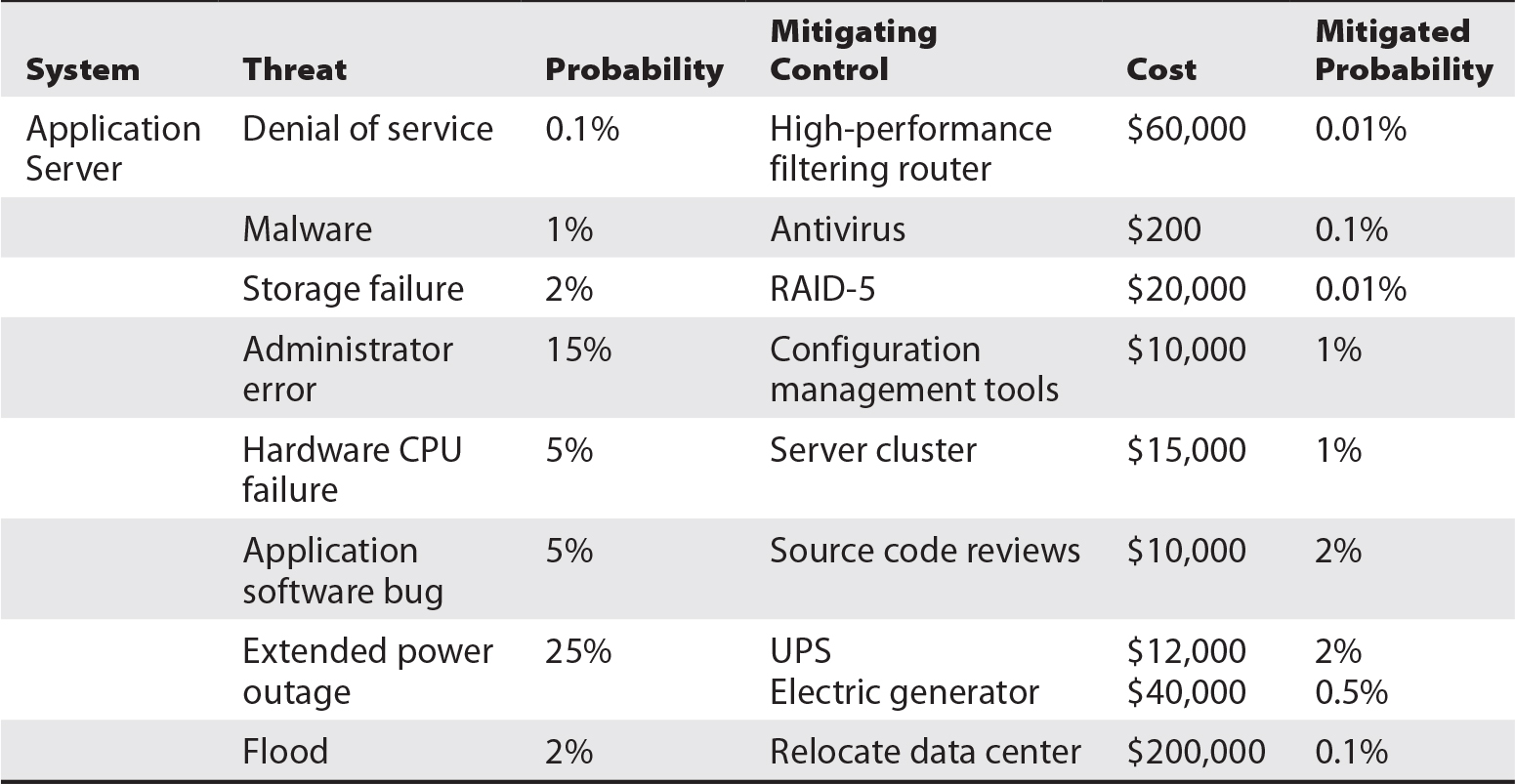

The criticality analysis is a study of each system and process, a consideration of the impact on the organization if it is incapacitated, the likelihood of incapacitation, and the estimated cost of mitigating the risk or impact of incapacitation. In other words, it’s a somewhat special type of risk analysis that focuses on key processes and systems.

The criticality analysis needs to include, or reference, a threat analysis. A threat analysis is a risk analysis that identifies every threat that has a reasonable probability of occurrence, plus one or more mitigating controls or compensating controls, and new probabilities of occurrence with those mitigating/compensating controls in place. In case you’re having a little trouble imagining what this looks like (I’m writing the book and I’m having trouble seeing this!), take a look at Table 5-12, which is a lightweight example of what I’m talking about.

Table 5-12 Example Threat Analysis Identifies Threats and Controls for Critical Systems and Processes

In the preceding threat analysis, notice the following:

- Multiple threats are listed for a single asset. In the table, I mentioned just eight threats. For all the threats but one, I listed only a single mitigating control. For the extended power outage threat, I listed two mitigating controls.

- Cost of downtime wasn’t listed. For systems or processes where you have a cost per unit of time for downtime, you’ll need to include it here, along with some calculations to show the payback for each control.

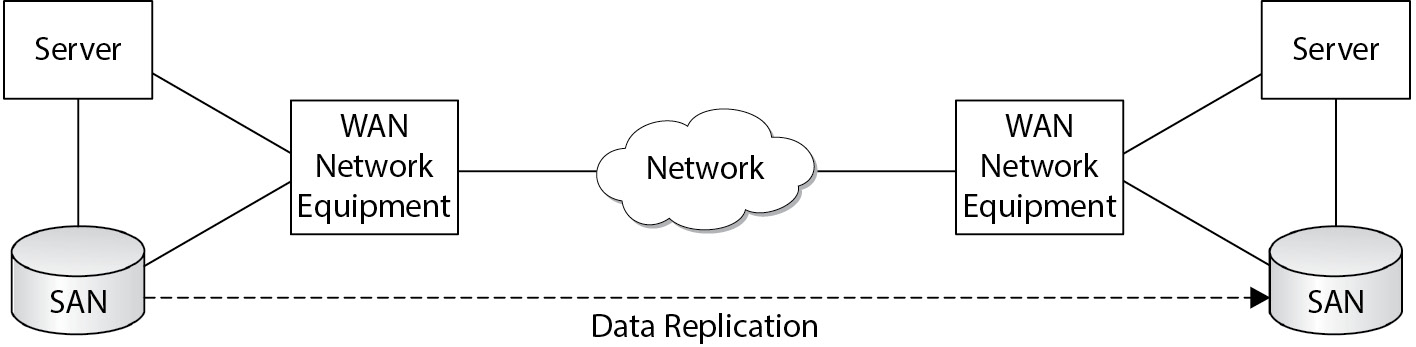

- Some mitigating controls can benefit more than one system. That may not have been obvious in this example, but in the case of a UPS (uninterruptible power supply) and electric generator, many systems can benefit, so the cost for these mitigating controls can be allocated across many systems, thereby lowering the cost for each system. Another example is a high-availability storage area network (SAN) located in two different geographic areas; while initially expensive, many applications can use the SAN for storage, and all will benefit from replication to the counterpart storage system.

- Threat probabilities are arbitrary. In Table 5-12, the probabilities were for a single occurrence in an entire year, so, for example, 5 percent means the threat will be realized once every 20 years.

- The length of outage was not included. You may need to include this also, particularly if you are quantifying downtime per hour or other unit of time.

It is probably becoming obvious that a threat analysis, and the corresponding criticality analysis, can get complicated. The rule here should be this: the complexity of the threat and criticality analyses should be proportional to the value of the assets (or revenue, or both). For example, in a company where application downtime is measured in thousands of dollars per minute, it’s probably worth taking a few weeks or even months to work out all of the likely scenarios and a variety of mitigating controls, and to work out which ones are the most cost-effective. On the other hand, for a system or business process where the impact of an outage is far less costly, a good deal less time might be spent on the supporting threat and criticality analysis.

EXAM TIP

Test-takers should ensure that any question dealing with BIA and CA places the business impact analysis first. Without this analysis, criticality analysis is impossible to evaluate in terms of likelihood or cost-effectiveness in mitigation strategies. The BIA identifies strategic resources and provides a value to their recovery and operation, which is, in turn, consumed in the criticality analysis phase. If presented with a question identifying BCP at a particular stage, make sure that any answers you select facilitate the BIA and then the CA before moving on toward objectives and strategies.

Determine Maximum Tolerable Downtime

The next step for each critical process is the establishment of a metric called maximum tolerable downtime (MTD). This is a theoretical time interval, measured from the onset of a disaster, after which the organization’s very survival is at risk. Establishing MTD for each critical process is an important step that aids in the establishment of key recovery targets, discussed in the next section.

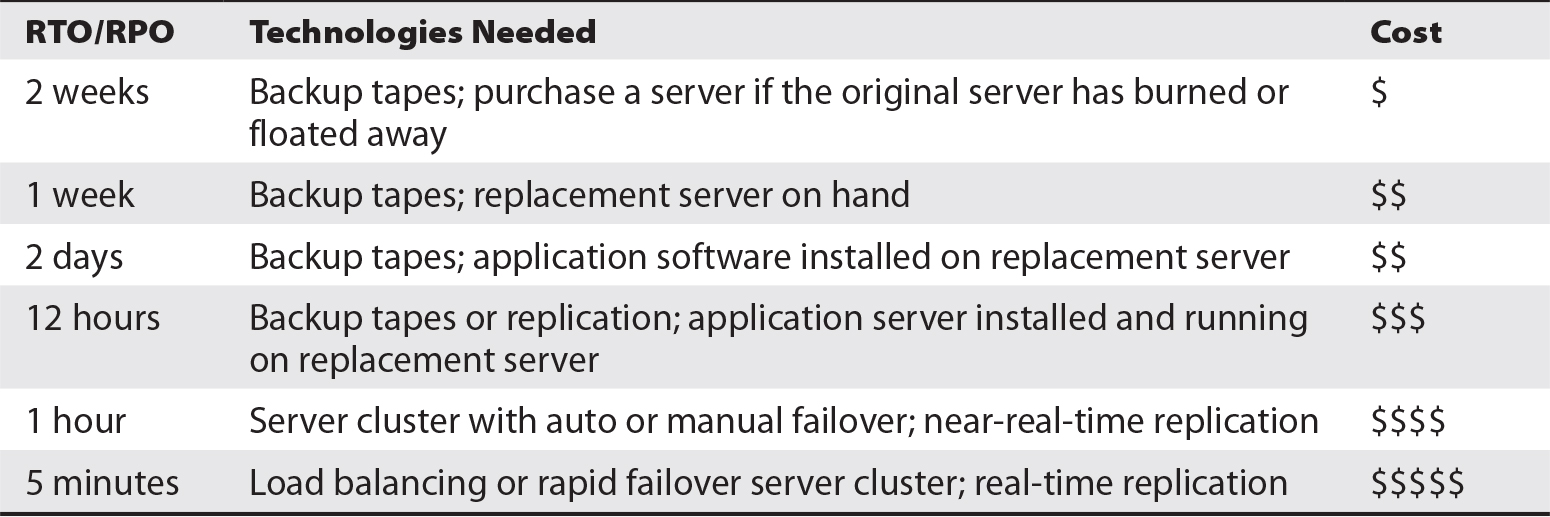

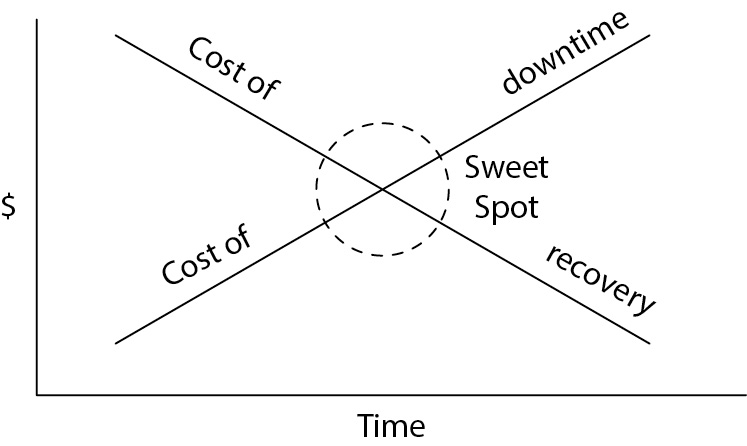

Establishing Key Recovery Targets

When the cost or impact of downtime has been established and the cost and benefit of mitigating controls has been considered, some key targets can be established for each critical process. These objectives determine how quickly key systems and processes should be made available after the onset of a disaster and the maximum tolerable data loss that results from the disaster. The two key recovery targets are

- Recovery time objective (RTO)

This refers to the maximum period that elapses from the onset of a disaster until the resumption of service. - Recovery point objective (RPO)

This refers to the maximum data loss from the onset of a disaster.

Once these target objectives are known, the disaster recovery (DR) team can begin to build system recovery capabilities and procedures that will help the organization economically realize these targets. This is discussed in detail later in this chapter.

Developing Continuity Plans

In the previous section, I discussed the notion of establishing recovery targets and the development of architectures, processes, and procedures. The processes and procedures are related to the normal operation of those new technologies as they will be operated in normal day-to-day operations. When those processes and procedures have been completed, the disaster recovery plans and procedures (actions that will take place during and immediately after a disaster) can be developed.

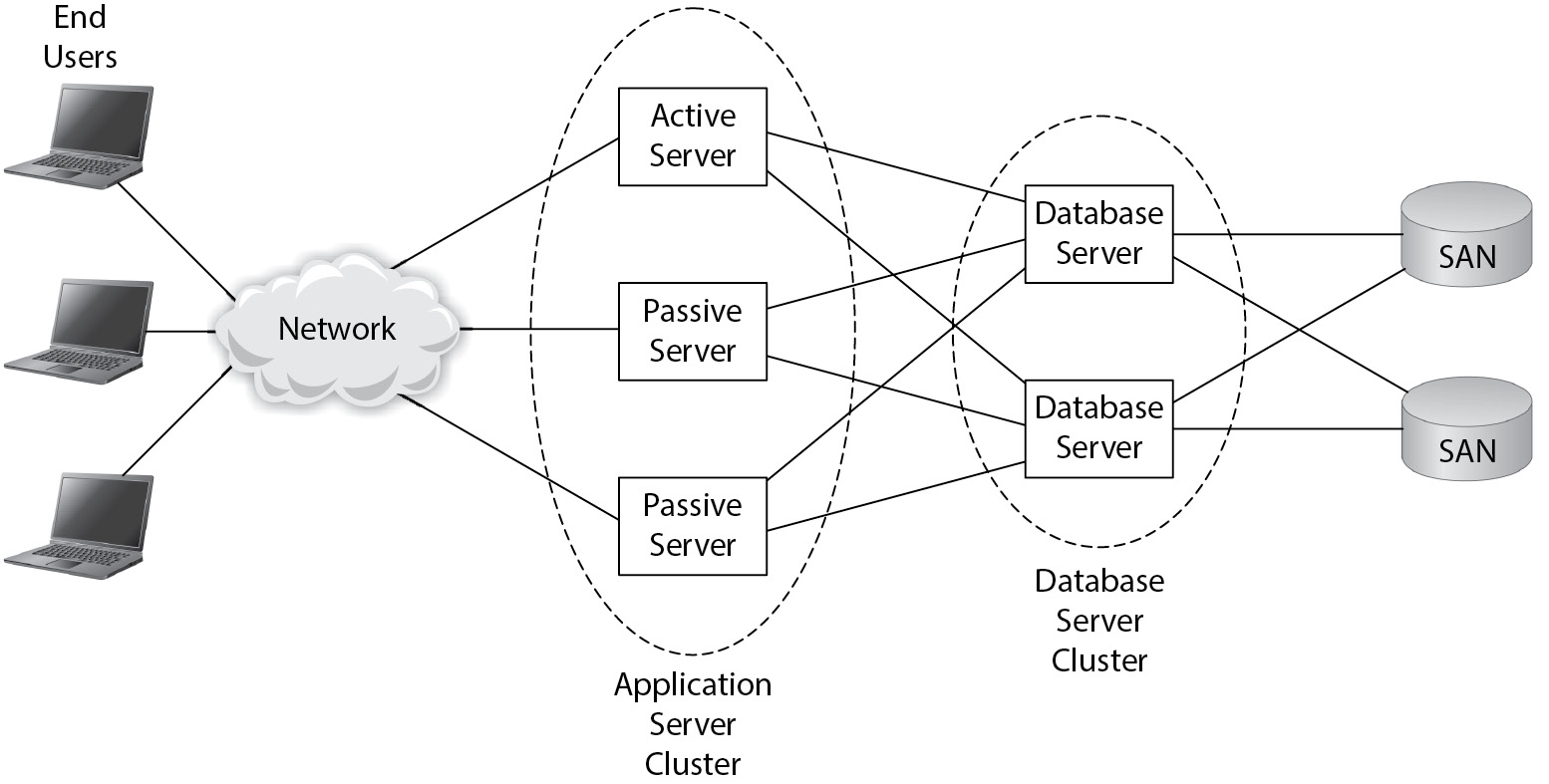

For example, an organization has established RPO and RTO targets for its critical applications. These targets necessitated the development of server clusters and storage area networks with replication. While implementing those new technologies, the organization developed the operations processes and procedures in support of those new technologies that would be carried out every day during normal business operations. As a separate activity, the organization would then develop the procedures to be performed when a disaster strikes the primary operations center for those applications; those procedures would include all of the steps that must be taken so that the applications can continue operating in an alternate location or in the public cloud.

The procedures for operating critical applications during a disaster are a small part of the entire body of procedures that must be developed. Several other sets of procedures must also be developed, including

- Personnel safety procedures

- Disaster declaration procedures

- Responsibilities

- Contact information

- Recovery procedures

- Continuing operations

- Restoration procedures

All of these are required so that an organization will be adequately prepared in the event a disaster occurs.

Personnel Safety Procedures

When a disaster strikes, measures to ensure the safety of personnel are a top priority and need to be taken immediately. If the disaster has occurred or is about to occur to a building, personnel may need to be evacuated as soon as possible. Arguably, however, in some situations, evacuation is exactly the wrong thing to do; for example, if a hurricane or tornado is bearing down on a facility, the building itself may be the best shelter for personnel, even if it incurs some damage. The point here is that personnel safety procedures need to be carefully developed, and possibly more than one set of procedures will be needed, depending on the event.

TIP

The highest priority in any disaster or emergency situation is the safety of human life.

Personnel safety procedures need to take many factors into account, including

- Ensuring that all personnel are familiar with evacuation and sheltering procedures

- Ensuring that visitors know how to evacuate the premises and the location of sheltering areas

- Posting signs and placards that indicate emergency evacuation routes and gathering areas outside of the building

- Locating emergency lighting to aid in evacuation or sheltering in place

- Providing fire extinguishment equipment (portable fire extinguishers and so on)

- Ensuring that people are able to communicate with public safety and law enforcement authorities, including in situations where communications and electric power have been cut off and when all personnel are outside of the building

- Caring for injured personnel

- Training in CPR and emergency first-aid

- Providing safety personnel who can assist in the evacuation of injured and disabled persons

- Providing the ability to account for visitors and other nonemployees

- Providing emergency shelter in extreme weather conditions

- Providing emergency food and drinking water

- Conducting periodic tests to ensure that evacuation procedures will be adequate in the event of a real emergency

Local emergency management organizations may have additional information available that can assist an organization with its emergency personnel safety procedures.

Disaster Declaration Procedures

Disaster response procedures are initiated when a disaster is declared. However, there needs to be a procedure for the declaration itself so that there will be little doubt as to the conditions that must be present.

Why is a disaster declaration procedure required? Primarily because it’s not always clear whether a situation is a real disaster. Sure, a 7.5 earthquake or a major fire is a disaster, but overcooking popcorn in the microwave and setting off a building’s fire alarm system might not be. Many “in between” situations may or may not be considered disasters. A disaster declaration procedure must state some basic conditions that will help determine whether a disaster should be declared.

Further, who has the authority to declare a disaster? What if senior management personnel frequently travel and may not be around? Who else can declare a disaster? And, finally, what does it mean to declare a disaster—and what happens next? The following points constitute the primary items that organizations need to consider for their disaster declaration procedure.

Form a Core Team

A core team of personnel needs to be established, all of whom will be familiar with the disaster declaration procedure, as well as the actions that must take place once a disaster has been declared. This core team should consist of middle and upper managers who are familiar with business operations, particularly those that are critical. This core team must be large enough so that a requisite few of them are on hand when a disaster strikes. In organizations that have second shift, third shift, and weekend workers, some of the core team members should be those in supervisory positions during those times. However, some of the core team members can be personnel who work “business hours” and are not on-site all of the time.

Declaration Criteria

The declaration procedure must contain some tangible criteria that a core team member can consult to guide him or her down the “Is this a disaster?” decision path.

The criteria for declaring a disaster should be related to the availability and viability of ongoing critical business operations. Some example criteria include any one or more of the following:

- Forced evacuation of a building containing or supporting critical operations that is likely to last for more than four hours

- Hardware, software, or network failures that result in a critical IT system being incapacitated or unavailable for more than four hours

- A major, prolonged outage by an Internet service provider or cloud service provider

- Any security incident that results in a critical IT system being incapacitated for more than four hours (security incidents could involve malware, break-in, attack, sabotage, and so on)

- Any event causing employee absenteeism or supplier shortages that, in turn, results in one or more critical business processes being incapacitated for more than eight hours

- Any event causing a communications failure that results in critical IT systems being unreachable for more than four hours

The preceding examples are a mostly complete list of criteria for many organizations. The duration periods will vary from organization to organization. For instance, a large, pure-online business such as Salesforce.com would probably declare a disaster if its main web sites were unavailable for more than a few minutes. But in an organization where computers are far less critical, an outage of four hours might not be considered a disaster.

- Pulling the Trigger

- When disaster declaration criteria are met, the disaster should be declared. The procedure for disaster declaration could permit any single core team member to declare the disaster, but it may be better to have two or more core team members agree on whether a disaster should be declared. Whether an organization should use a single-person declaration or a group of two or more is each organization’s choice.

All core team members empowered to declare a disaster should have the procedure on hand at all times. In most cases, the criteria should fit on a small, laminated wallet card that each team member can keep close at all times. For organizations that use the consensus method for declaring a disaster, the wallet card should include the names and contact numbers for other core team members so that each will have a way of contacting others.

Next Steps

Declaring a disaster will trigger the start of one or more other response procedures, but not necessarily all of them. For instance, if a disaster is declared because of a serious computer or software malfunction, there is no need to evacuate the building. While this example may be obvious, not all instances will be this clear. Either the disaster declaration procedure itself or each of the subsequent response procedures should contain criteria that will help determine which response procedures should be enacted.

False Alarms

Probably the most common cause of personnel not declaring a disaster is the fear that an actual disaster is not taking place. Core team members empowered with declaring a disaster should not necessarily hesitate. Instead, core team members could convene with additional core team members to reach a firm decision, provided this can be done quickly.

If a disaster has been declared and later it is clear that a disaster has been averted (or did not exist in the first place), the disaster can simply be called off and declared to be over. Response personnel can be contacted and told to cease response activities and return to their normal activities.

TIP

Depending on the level of effort that takes place in the opening minutes and hours of disaster response, the consequences of declaring a disaster when none exists may or may not be significant. In the spirit of continuous improvement, any organization that has had a few false alarms should seek to improve their disaster declaration criteria or procedures. Well-trained and experienced personnel can usually reduce the frequency of false alarms.

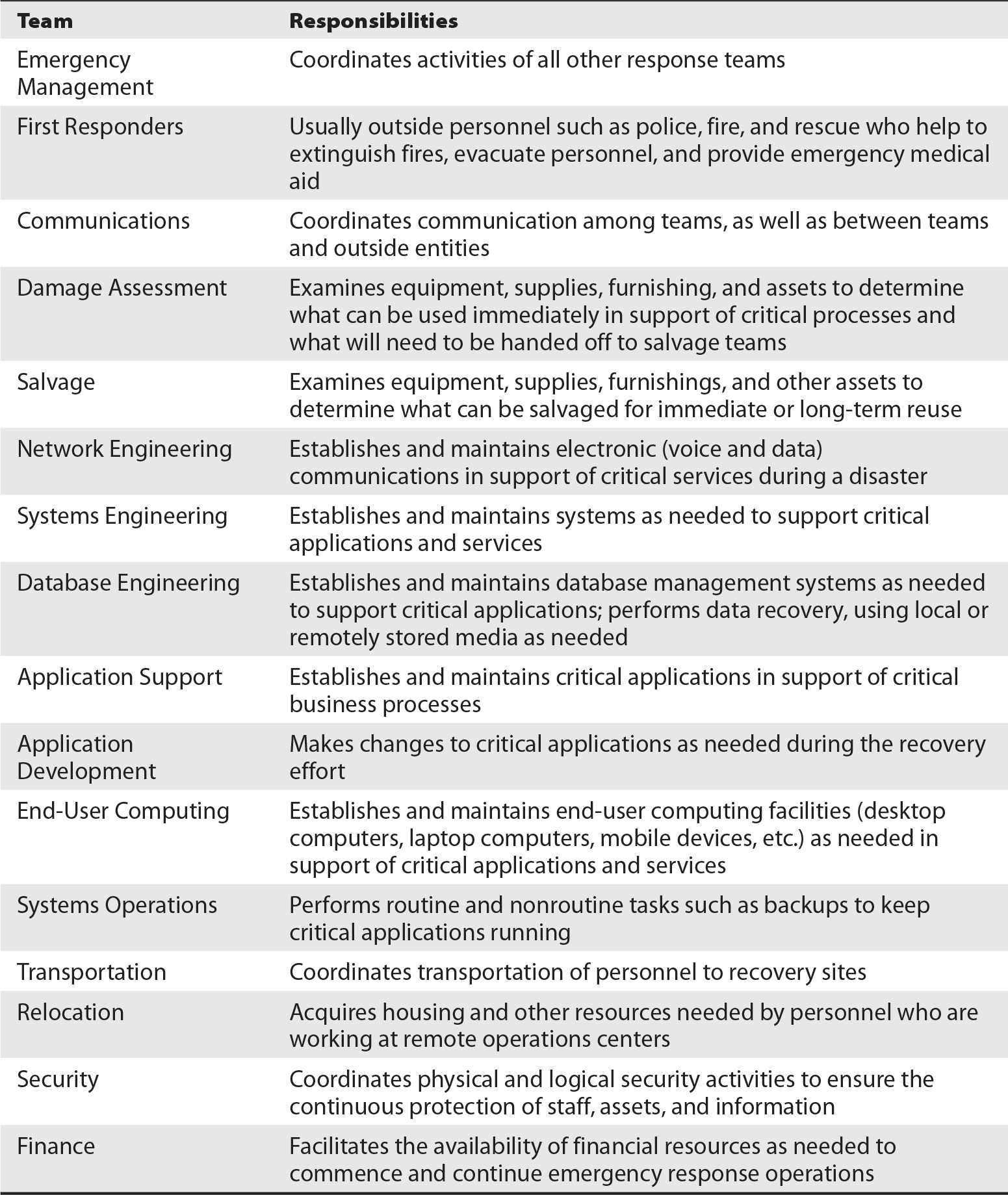

Disaster Responsibilities

During a disaster, many important tasks must be performed to evacuate or shelter personnel, assess damage, recover critical processes and systems, and carry out many other functions that are critical to the survival of the enterprise.

About 20 different responsibilities are described here. In a large organization, each responsibility may be staffed with a team of two, three, or many individuals. In small organizations, a few people may incur many responsibilities each, switching from role to role as the situation warrants.

All of these roles should be staffed by people who are available. It is important to remember that many of the “ideal” persons to fill each role may be unavailable during a disaster for several reasons, including the following:

- Injured, ill, or deceased

Some regional disasters will inflict widespread casualties that will include some proportion of response personnel. Those who are injured, ill (in the case of a pandemic, for instance, or who are recovering from a sickness or surgery when the disaster occurs), or who are killed by the disaster are clearly not going to be showing up to help. - Caring for family members

Some types of disasters may cause widespread injury or require mass evacuation. In some of these situations, many personnel will be caring for family members whose immediate needs for safety will take priority over the needs of the workplace. - Unavailable transportation

Some types of disasters include localized or widespread damage to transportation infrastructure, which may result in many persons who are willing to be on-site to help with emergency operations being unable to travel to the work site. - Out of the area

Some disaster response personnel may be away on business travel or on vacation and be unable to respond. However, some persons being away may actually be opportunities in disguise; unaffected by the physical impact of the disaster, they may be able to help out in other ways, such as communications with suppliers, customers, or other personnel. - Communications

Some types of disasters, particularly those that are localized (versus widespread and obvious to an observer), require that disaster response personnel be contacted and asked to help. If a disaster strikes after hours, some personnel may be unreachable. - Fear

Some types of disasters (such as pandemic, terrorist attack, flood, and so on) may instill fear for safety on the part of response personnel who will disregard the call to help and stay away from the work site.

NOTE

Response personnel in all disciplines and responsibilities will need to be able to piece together whatever functionality they are called on to do, using whatever resources are available—this is part art and part science. Although response and contingency plans may make certain assumptions, personnel may find themselves with fewer resources than they need, requiring them to do the best they can with the resources available.

Each role will be working with personnel in many other roles, often working with unfamiliar persons. An entire response and recovery operation may be operating almost like a brand-new organization in unfamiliar settings and with an entirely new set of rules. In typical organizations, teams work well when team members are familiar with, and trust, one another. In a response and recovery operation, the stress level is much higher because the stakes—company survival—are higher, and often the teams are composed of persons who have little experience with one another and these new roles. This will cause additional stress that will bring out the best and worst in people, as illustrated in Figure 5-29.

Figure 5-29 Stress is compounded by the pressure of disaster recovery and the formation of new teams in times of chaos.

Emergency Response

These are the first responders during a disaster. Their top priorities include evacuation or sheltering of personnel, first aid, triage of injured personnel, and possibly firefighting.

Command and Control (Emergency Management)

During disaster response operations, someone must be in charge. In a disaster, resources may be scarce, and many matters will vie for attention. Someone needs to fill the role of decision maker to keep disaster response activities moving and to handle situations that arise. This role may need to be rotated among various personnel, particularly in smaller organizations, to counteract fatigue.

TIP

Although the first person on the scene may be the person in charge initially, that will definitely change as qualified assigned personnel show up and take charge and as the nature of the disaster and response solidifies. The leadership roles may then be passed among key personnel already designated to be in charge.

Documentation

It’s vital that one or more persons continually document the important events during disaster response operations. From decisions, to discussions, to status, to roll call, these events must be written down (and later recorded digitally), so that the details of disaster response can be pieced together afterward. This will help the organization better understand how disaster response unfolded, how decisions were made, and who performed which actions, all of which will help the organization be better prepared for future events.

Internal and External Communications

In many disaster scenarios, personnel may be stripped of many or all of their normal means of communication, such as desk phone, voicemail, e-mail, smartphone, and instant messaging. Yet never are communications as vital as during a disaster, when nothing is going according to plan. Internal communications are needed so that status on various activities can be sent to command and control, and so that priorities and orders can be sent to disaster response personnel.

People outside of the organization also need to know what’s going on when a disaster strikes. There’s a potentially long list of parties who want or need to know the status of business operations during and after a disaster, including

- Customers

- Suppliers

- Partners

- Shareholders

- Neighbors

- Regulators

- Media

- Law enforcement and public safety authorities

These different audiences need different messages, as well as messages in different forms.

- Legal and Compliance

Several needs may arise during a disaster that require the attention of inside or outside legal counsel. Disasters present unique situations that need legal assistance, such as- Interpretation of regulations

- Interpretation of contracts with suppliers and customers

- Management of matters of liability to other parties

TIP

Typical legal matters need to be resolved before the onset of a disaster, with this information included in disaster response procedures, since legal staff members may be unavailable during a disaster.

Damage Assessment

Whether a disaster is a physically violent event, such as an earthquake or volcano, or instead involves no physical manifestation, such as a serious security incident, one or more experts are needed who can examine affected assets and accurately assess the damage. Because most organizations own many different types of assets (from buildings, to equipment, to information), qualified experts are needed to assess each asset type involved. It is not necessary to call upon all available experts—only those whose expertise matches the type of event that has occurred need to be consulted.

Some expertise may go well beyond the skills present in an organization, such as a building structural engineer who can assess potential earthquake damage. In such cases, it may be sensible to retain the services of an outside engineer who will respond and provide an assessment on whether a building is safe to occupy after a disaster. In fact, it may make sense to retain more than one, in case one or more of them is affected by a disaster.

Salvage

Disasters destroy assets that the organization uses to make products or perform services. When a disaster occurs, someone (either a qualified employee or an outside expert) needs to examine assets to determine which are salvageable; then a salvage team needs to perform the actual salvage operation at a pace that meets the organization’s needs.

In some cases, salvage may be a critical-path activity, where critical processes are paralyzed until salvage and repairs or replacements to critically needed machinery can be performed. In other cases, the salvage operation is performed on inventory of finished goods, raw materials, and other items so that business operations can be resumed. Occasionally, when it is obvious that damaged equipment or materials are a total loss, the salvage effort involves selling the damaged items or materials to another organization.

Assessment of damage to assets may be a high priority when an organization will be filing an insurance claim. Insurance may be a primary source of funding for the organization’s recovery effort.

CAUTION

Salvage operations may be a critical-path activity or one that can be carried out well after the disaster. To the greatest extent possible, this should be decided in advance. Otherwise, the command-and-control function will need to decide the priority of salvage operations.

Physical Security

After a disaster, the organization’s usual physical security controls may be compromised. For instance, fencing, walls, and barricades could be damaged, or video surveillance systems may be disabled or have no electric power. These and other failures could lead to increased risk of loss or damage to assets and personnel until those controls can be restored. Also, security controls in temporary quarters such as hot/warm/cold sites and temporary work centers may be inadequate compared to those in primary locations.

Supplies

During emergency and recovery operations, personnel will require supplies of many kinds, from food and drinking water, writing tablets, and pens, to smartphones, portable generators, and extension cords. This function may also be responsible for ordering replacement assets such as servers and network equipment for a cold site.

Transportation

When workers are operating from a temporary location and/or if regional or local transportation systems have been compromised, many arrangements for all kinds of transportation may be required to support emergency operations. These can include transportation of replacement workers, equipment, or supplies by truck, car, rail, sea, or air. The transportation function could also be responsible for arranging for temporary lodging for personnel.

Networks

This technology function is responsible for damage assessment to the organization’s voice and data networks, building/configuring networks for emergency operations, or both. This function may require extensive coordination with external telecommunications service providers, who, by the way, may be suffering the effects of a local or regional disaster as well.

Network Services

This function is responsible for network-centric services such as Domain Name System (DNS), Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP), network routing, and authentication.

Systems

This function is responsible for building, loading, and configuring the servers and systems that support critical services, applications, databases, and other functions. Personnel may have other resources such as virtualization technology to enable additional flexibility.

Database Management Systems

For critical applications that rely upon database management systems, this function is responsible for building databases on recovery systems and for restoring or recovering data from backup media, replication volumes, or e-vaults onto recovery systems. Database personnel will need to work with systems, network, and applications personnel to ensure that databases are operating properly and are available as needed.

Data and Records

This function is responsible for access to and re-creation of electronic and paper business records. This is a business function that supports critical business processes and works with database management personnel and, if necessary, with data-entry personnel to rekey lost data.

Applications

This function is responsible for recovering application functionality on application servers. This may include reloading application software, performing configuration, provisioning roles and user accounts, and connecting the application to databases, network services, and other application integration issues.

Access Management

This function is responsible for creating and managing user accounts for network, system, and application access. Personnel with this responsibility may be especially susceptible to social engineering and be tempted to create user accounts without proper authority or approval.

Information Security and Privacy

Personnel who serve in this capacity are responsible for ensuring that proper security controls are being carried out during recovery and emergency operations. They will be expected to identify risks associated with emergency operations and to require remedies to reduce risks.

Security personnel will also be responsible for enforcing privacy controls so that employee and customer personal data will not be compromised, even as business operations are affected by the disaster.

Off-site Storage

This function is responsible for managing the effort of retrieving backup media from off-site storage facilities and for protecting that media in transit to the scene of recovery operations. If recovery operations take place over an extended period (more than a couple of days), data at the recovery site will need to be backed up and sent to an off-site media storage facility to protect that information should a disaster occur at the hot/warm/cold site (and what bad luck that would be!).

User Hardware

In many organizations, little productive work gets done when employees don’t have their workstations, printers, scanners, copiers, and other office equipment. Thus, a user hardware function is required to provide, configure, and support the variety of office equipment required by end users working in temporary or alternate locations. This function, like most others, will have to work with many others to ensure that workstations and other equipment are able to communicate with applications and services as needed to support critical processes.

Training

During emergency operations, when response personnel and users are working in new locations (and often on new or different equipment and software), some personnel may need training so that their productivity can be quickly restored. Training personnel will need to be familiar with many disaster response and recovery procedures so that they can help people in those roles understand what is expected of them. This function will also need to be able to dispense emergency operations procedures to these personnel.

Restoration

This function comes into play when IT is ready to migrate applications running on hot/warm/cold site systems back to the original (or replacement) processing center.

Contract Information

This function is responsible for understanding and interpreting legal contracts. Most organizations are a party to one or more legal contracts that require them to perform specific activities, provide specific services, and communicate status if service levels have changed. These contracts may or may not have provisions for activities and services during disasters, including communications regarding any changes in service levels.

This function is vital not only during the disaster planning stages but also during actual disaster response. Customers, suppliers, regulators, and other parties need to be informed according to specific contract terms.

Recovery Procedures

Recovery procedures are the instructions that key personnel use to bootstrap services (such as IT systems and other business-enabling technologies) that support the critical business functions identified in the BIA and CA. The recovery procedures should work hand-in-hand with the technologies that may have been added to IT systems to make them more resilient.

An example would be useful here: A fictitious company, Acme Rocket Boots, determines that its order-entry business function is highly critical to the ongoing viability of the business and sets recovery objectives to ensure that order entry would be continued within no more than 48 hours after a disaster. Acme determines that it needs to invest in storage, backup, and replication technologies to make a 48-hour recovery possible. Without these investments, IT systems supporting order-entry would be down for at least ten days until they could be rebuilt from scratch. Acme cannot justify the purchase of systems and software to facilitate an auto-failover of the order-entry application to hot-site DR servers. Instead, the recovery procedure would require that the database be rebuilt from replicated data on cloud-based servers. Other tasks, such as installing recent patches, would also be necessary to make recovery servers ready for production use. All of the tasks required to make the systems ready constitute the body of recovery procedures needed to support the business order-entry function.

This example is, of course, a gross oversimplification. Actual recovery procedures could take potentially dozens of pages of documentation, and procedures would also be necessary for network components, end-user workstations, network services, and other supporting IT services required by the order-entry application. And those are the procedures needed just to get the application running again. More procedures would be needed to keep the applications running properly in the recovery environment.

Continuing Operations Procedures

Procedures for continuing operations have more to do with business processes than they do with IT systems. However, the two are related, since the procedures for continuing critical business processes have to fit hand-in-hand with the procedures for operating supporting IT systems that may also (but not necessarily) be operating in a recovery or emergency mode.

Let me clarify that last statement: It is entirely conceivable that a disaster could strike an organization with critical business processes that operate in one city but that are supported by IT systems located in another city. A disaster could strike the city with the critical business function, which means that personnel may have to continue operating that business function in another location, on the original, fully featured IT application. It is also possible that a disaster could strike the city with the IT application, forcing it into an emergency/recovery mode in an alternate location, while users of the application are operating in a mostly business-as-usual mode. And, of course, a disaster could strike both locations (or a disaster could strike in one location where both the critical business function and its supporting IT applications reside), throwing both the critical business function and its supporting IT applications into emergency mode. Any organization’s reality could be even more complex than this: just add dependencies on external application service providers, applications with custom interfaces, or critical business functions that operate in multiple cities. If you wondered why disaster recovery and business continuity planning were so complicated, perhaps your appreciation has grown just now.

Restoration Procedures

When a disaster has occurred, IT operations need to take up residence temporarily in an alternate processing site while repairs are performed on the original site. Once those repairs are completed, IT operations would need to be transitioned back to the main (or replacement) processing facility. You should expect that the procedures for this transition would also be documented (and tested—testing is discussed later in this chapter).

NOTE

Transitioning applications back to the original processing site is not necessarily just a second iteration of the initial move to the cloud/hot/warm/cold site. Far from it: the recovery site may have been a skeleton (in capacity, functionality, or both) of its original self. The objective is not necessarily to move the functionality at the recovery site back to the original site, but to restore the original functionality to the original site.

Let’s continue the Acme Rocket Boots example: The company’s order-entry application at the DR site had only basic, not extended, functions. For instance, customers could not look at order history, and they could not place custom orders; they could order only off-the-shelf products. But when the application is moved back to the primary processing facility, the history of orders accumulated on the DR application needs to be merged into the main order history database, which was not a part of the DR plan.

Considerations for Continuity and Recovery Plans

A considerable amount of detailed planning and logistics must go into continuity and recovery plans if they are to be effective.

Availability of Key Personnel

An organization cannot depend upon every member of its regular expert workforce to be available in a disaster. As discussed earlier in this chapter in more detail, personnel may be unavailable for a number of reasons, including

- Injury, illness, or death

- Caring for family members

- Unavailable transportation

- Damaged transportation infrastructure

- Being out of the area

- Lack of communications

- Fear related to the disaster and its effects

TIP

An organization must develop thorough and accurate recovery and continuity documentation as well as cross-training and plan testing. When a disaster strikes, an organization has one chance to survive, and survival depends upon how well the available personnel are able to follow recovery and continuity procedures and to keep critical processes functioning properly.

A successful disaster recovery operation requires available personnel who are located near company operations centers. While the primary response personnel may consist of the individuals and teams responsible for day-to-day corporate operations, others need to be identified. In a disaster, some personnel will be unavailable for many reasons.

Key personnel, as well as their backup persons, need to be identified. Backup personnel can consist of employees who have familiarity with specific technologies, such as operating system, database, and network administration, and who can cover for primary personnel if needed. Sure, it would be desirable for these backup personnel also to be trained in specific recovery operations, but at the very least, if these personnel have access to specific detailed recovery procedures, having them on a call list is probably better than having no available personnel during a disaster.

Besides employees, many other parties need to be notified in the event of a disaster. Outside parties need to be aware of the disaster as well as of basic changes in business conditions.

In a regional disaster such as a hurricane or earthquake, nearby parties will certainly be aware of the disaster and that your organization is involved in it somehow. However, those parties may not be aware of the status of business operations immediately after the disaster: a regional event’s effects can range from complete destruction of buildings and equipment to no damage at all and business-as-usual conditions. Unless key parties are notified of the status, they may have no other way to know for sure.

Parties that need to be contacted may include

- Key suppliers

This may include electric and gas utilities, fuel delivery, and materials delivery. In a disaster, an organization will often need to impart special instructions to one or more suppliers, requesting delivery of extra supplies or temporary cessation of deliveries. - Key customers

Many organizations have key customers whose relationships are valued above most others. These customers may depend on a steady delivery of products and services that are critical to their own operations; in a disaster, those customers may have a dire need to know whether such deliveries will be able to continue or not and under what circumstances. - Public safety

Police, fire, and other public safety authorities may need to be contacted, not only for emergency operations such as firefighting, but also for any required inspections or other services. It is important that “business office” telephone numbers for these agencies be included on contact lists, as 911 and other emergency lines may be flooded by calls from others. - Insurance adjusters

Most organizations rely on insurance companies to protect their assets from damage or loss in a disaster. Because insurance adjustment funds are often a key part of continuing business operations in an emergency, it’s important to be able to reach insurers as soon as possible after a disaster has occurred. - Regulators

In some industries, organizations are required to notify regulators of certain types of disasters. While regulators obviously may be aware of noteworthy regional disasters, they may not immediately know of an event’s specific effects on an organization. Further, some types of disasters are highly localized and may not be newsworthy, even in a local city. - Media

Media outlets such as newspapers and television stations may need to be notified as a means of quickly reaching the community or region with information about the effects of a disaster on organizations. - Shareholders

Organizations are usually obliged to notify their shareholders of any disastrous event that affects business operations. This may be the case whether the organization is publicly or privately held.

The persons or teams responsible for communicating with these outside parties will need to have all of the individuals and organizations included in a list of parties to contact. This information should all be included in emergency response procedures.

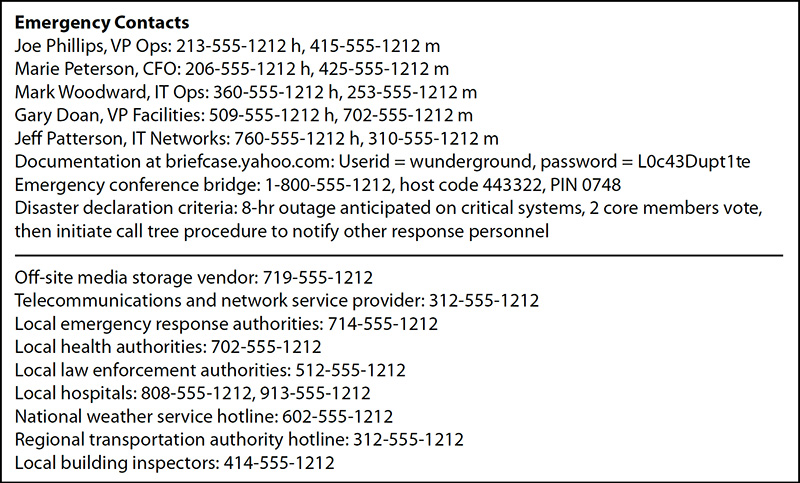

Wallet cards containing emergency contact information should be prepared for core team personnel for the organization as well as for members in each department who would be actively involved in disaster response. Wallet cards are advantageous, because most personnel will have a wallet, notebook, or purse nearby at all times, even when away from home, running errands, traveling, or on vacation. Information on the wallet card should include contact information for fellow team members, a few of the key disaster response personnel, and any conference bridges or emergency call-in numbers that are set up. An example wallet card is shown in Figure 5-30.

Figure 5-30 Example laminated wallet card for core team participants with emergency contact information and disaster declaration criteria

Emergency Supplies

The onset of a disaster may cause personnel to be stranded at a work location, possibly for several days. This can be caused by a number of reasons, including inclement weather that makes travel dangerous or a transportation infrastructure that is damaged or blocked with debris.

Emergency supplies should be laid up at a work location and made available to personnel stranded there, regardless of whether they are supporting a recovery effort or not (it’s also possible that severe weather or a natural or human-made event could make transportation dangerous or impossible).

A disaster can also prompt employees to report to a work location (at the primary location or at an alternate site) where they may remain for days at a time, even around the clock if necessary. A situation like this may make the need for emergency supplies less critical, but it still may be beneficial to the recovery effort to make supplies available to support recovery personnel.

An organization stocking emergency supplies at a work location should consider including the following items:

- Drinking water

- Food rations

- First-aid supplies

- Blankets

- Flashlights

- Battery or crank-powered radio

Local emergency response authorities may recommend other supplies be kept at a work location as well.

Communications

Communications within organizations, as well as with customers, suppliers, partners, shareholders, regulators, and others, is vital under normal business conditions. During a disaster and subsequent recovery and restoration operations, such communications are more important than ever, while many of the usual means for communications may be impaired.

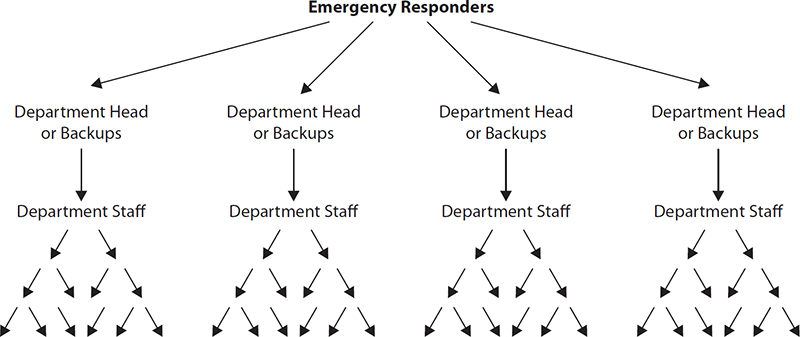

Disaster response procedures need to include a call tree. This is a method where the first personnel involved in a disaster begin notifying others in the organization, informing them of the developing disaster and enlisting their assistance. Just as the branches of a tree originate at the trunk and are repeatedly subdivided, a call tree is most effective when each person in the tree can make just a few phone calls. Not only will the notification of important personnel proceed more quickly, but each person will not be overburdened with many calls.

Remember that in a disaster a significant portion of personnel may be unavailable or unreachable. Therefore, a call tree should be structured so that there is sufficient flexibility as well as assurance that all critical personnel will be contacted. Figure 5-31 shows an example call tree.

Figure 5-31 Example call tree structure

An organization can also use an automated outcalling system to notify critical personnel of a disaster. Such a system can play a prerecorded message or request that personnel call an information number to hear a prerecorded message. Most outcalling systems keep a log of which personnel have been successfully reached.

An automated calling system should not be located in the same geographic region as the disaster. A regional disaster could damage the system or make it unavailable during a disaster. The system should be Internet accessible so that response personnel can access it to determine which personnel have been notified and to make any needed changes before or during a disaster.

Transportation

Some types of disasters may make certain modes of transportation unavailable or unsafe. Widespread natural disasters, such as earthquakes, volcanoes, hurricanes, and floods, can immobilize virtually every form of transportation, including highways, railroads, boats, and airplanes. Other types of disasters may impede one or more types of transportation, which could result in overwhelming demand for the available modes. High volumes of emergency supplies may be needed during and after a disaster, but damaged transportation infrastructure often makes the delivery of those supplies difficult.

- Components of a Business Continuity Plan

The complete set of business continuity plan documents will include the following:- Supporting project documents

These will include the documents created at the beginning of the business continuity project, including the project charter, project plan, statement of scope, and statement of support from executives. - Analysis documents

These include the- Business impact analysis (BIA)

- Threat assessment and risk assessment

- Criticality analysis

- Documents defining approved recovery targets such as recovery time objective (RTO) and recovery point objective (RPO)

- Response documents

These are all the documents that describe the required action of personnel when a disaster strikes, plus documents containing information required by those same personnel. Examples of these documents include - Business recovery (or resumption) plan

This describes the activities required to recover and resume critical business processes and activities. - Occupant emergency plan (OEP)

This describes activities required to care for occupants safely in a business location during a disaster. This will include both evacuation procedures and sheltering procedures, each of which may be required, depending upon the type of disaster that occurs. - Emergency communications plan

This describes the types of communications imparted to many parties, including emergency response personnel, employees in general, customers, suppliers, regulators, public safety organizations, shareholders, and the public. - Contact lists

These contain names and contact information for emergency response personnel as well as for critical suppliers, customers, and other parties. - Disaster recovery plan

This describes the activities required to restore critical IT systems and other critical assets, whether in alternate or primary locations. - Continuity of operations plan (COOP)

This describes the activities required to continue critical and strategic business functions at an alternate site. - Security incident response plan (SIRP)

This describes the steps required to deal with a security incident that could reach disastrous proportions. - Test and review documents

This is the entire collection of documents related to tests of all of the different types of business continuity plans, as well as reviews and revisions to documents.

- Supporting project documents

Testing Recovery and Continuity Plans

It’s surprising what you can accomplish when no one is concerned about who gets the credit.

*–*Ronald Reagan