CYB306 Cyber-Physical Vehicle System Security

Chapter 9: Transportation Cyber-Physical System as a Specialised Education Stream

Objectives

- Introduction

- Background

- A cyber-physical system workforce

- Required knowledge and skills

- Curriculum delivery mechanism

- Conclusions

1. Introduction

Cyber-Physical Systems (CPSs) are often highly complex, and sometimes mission-critical systems comprising physical components monitored and controlled by embedded computational cores usually requiring real-time responses (e.g., autonomous collision avoidance in driverless cars).

They could comprise hundreds of embedded control units in a single system (such as an automobile) or many heterogeneous systems, each with hundreds of thousands of embedded control units, such as a city transport management system.

Such systems are networked frequently (but not always) through internet protocols, when they are referred to as the Internet of Things.

These are already complex systems, but one must also consider the frequent and multimodal interactions of human beings (as originators, developers, operators, end users and possibly as malicious hackers) with the CPS, which adds a further layer of complexity and a significant quotient of non-engineering specialist knowledge needed for design and operation of CPS.

Developing an effective higher education curriculum in any interdisciplinary domain should be addressed through a ‘fundamental purposes of the inquiry’, and in the context of this book, the purpose of this chapter is to look into higher education in the specific CPS domain of TCPS.

2. Background

2.1 Academic disciplines

Academic disciplines traditionally focused on a well-defined body of knowledge as a distinguishable branch of a faculty (e.g., science, humanities, social sciences, engineering.).

There is significant international variation in the breadth of study, what one might term the ‘purity’ of the disciplines that are taught to degree level.

In recent decades, two developments have been added to the breadth of courses offered by universities: firstly, joint honours degrees gained some popularity, although the two subjects were often within the same faculty; secondly, courses began to reflect types of application (e.g., mechatronics).

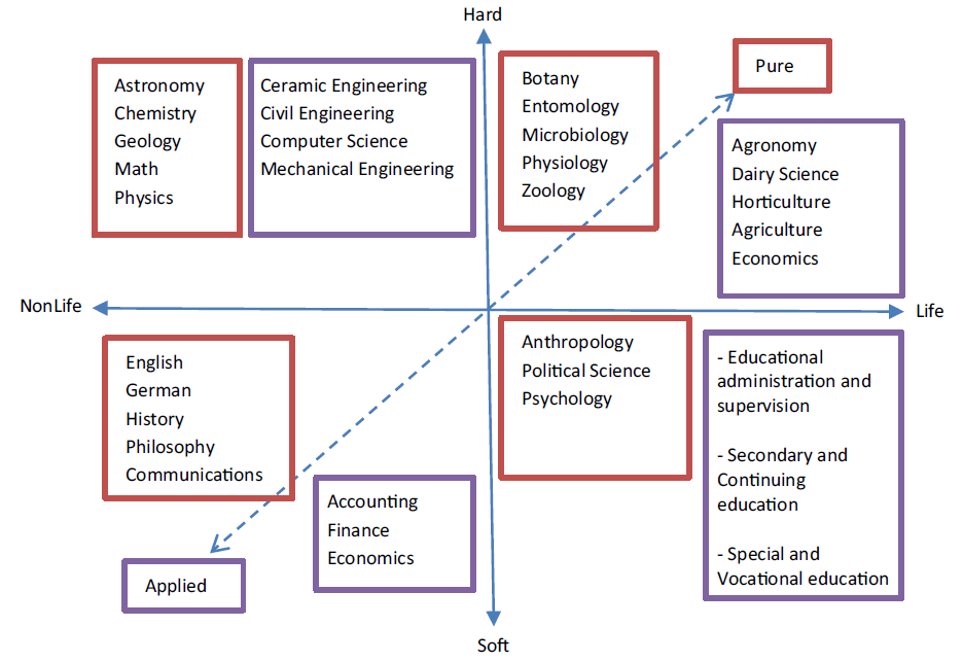

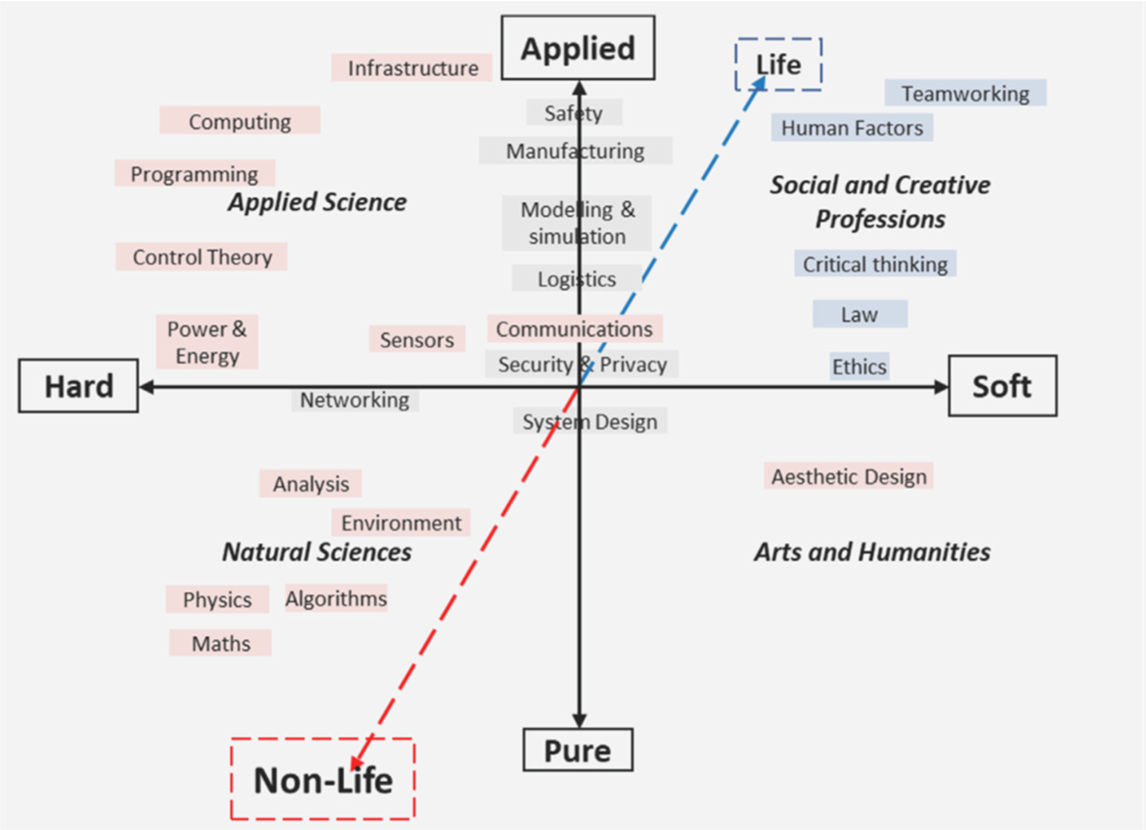

Academic disciplines classified along the dimensions of hard or soft (i.e., material-centric or human-centric), nonlife systems or life systems and pure (typically theoretical) or applied, as shown in Fig. 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Classification of academic disciplines due to Anthony Biglan [14].

Figure 9.1 Classification of academic disciplines due to Anthony Biglan [14].

2.2 Transportation systems

The ambition of humankind to travel further, faster and safer has led to increasing sophistication in terms of transportation systems and a concomitant increase in the complexity of those systems.

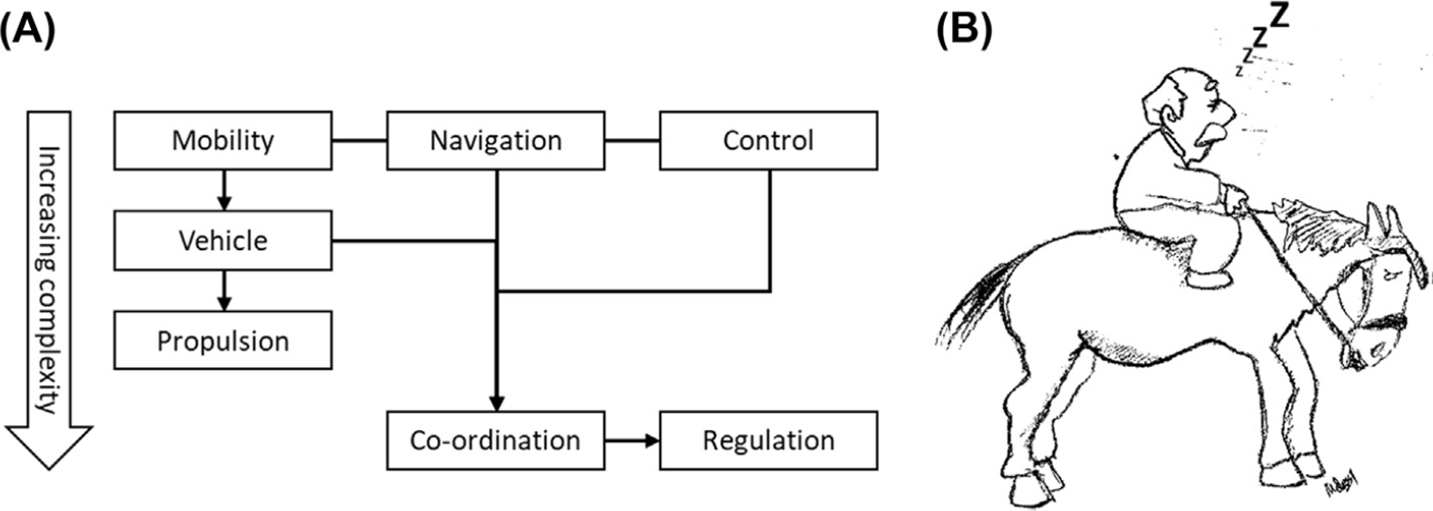

At its most basic, a transportation system comprises simply the ability to be mobile and the ability to navigate and control (Fig. 9.2).

A next step is the use of a vehicle (in early times these might be beasts of burden1), and different means of propulsion were developed for different domains and terrains.

As the means of transport became more widespread and numerous, a level of coordination is required and even in early times regulation became an essential aspect of coordinating vehicles.

At the time of writing, TCPS is enabling new methods of coordination and there is significant attention and effort being devoted to development of appropriate regulation.

Figure 9.2 (A) Evolution of transportation systems and (B) early autonomous transport. Cartoon by Miles J de C Henshaw.

2.3 The need for Transportation Cyber-Physical Systemengineers

CPSs have evolved from the discipline of embedded systems, for which there was a clear demarcation between hardware, software and firmware design to the present state where hardware, software and firmware are intricately integrated with each aspect impacting the other.

The demarcation defined three distinct groups of designers, but the degree of integration means that each group must now be intimately knowledgeable about the other two.

The evolution can be mostly attributed to advancement in computer science (resulting in system functionalities shifting from hardware to software), advancement in communications technology (particularly wireless technology facilitating connection of the computational cores) and an increase in the number of transistors per integrated circuit in accordance to Moore’s law (leading to miniaturisation).

Not only is the prediction of emergent behaviour significantly more difficult for CPS but also there are new risks associated with safety and cybersecurity, and new design approaches are needed.

As a result, education programmes in CPS are beginning to emerge; furthermore, it is recommended by the US Academy of Sciences that CPS education be incorporated into undergraduate courses in engineering and computer science.

3. A cyber-physical system workforce

- As CPS considerations become urgent, it has been suggested that the future CPS workforce will comprise three types:

- Engineers from traditional disciplines such as electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, systems engineering, control engineering, computer science, etc.

- Engineers trained in particular application areas or in subdisciplines, such as aerospace, civil engineering, vehicle engineering, transportation engineering, etc.

- Specially trained CPS engineers (specialising in its various domains such as TCPS) whose realm of knowledge will lie at the cusp of ‘cyber’ and the ‘physical’ world.

- The US National Academy of Sciences strongly recommends that CPS educational programmes should emphasise the interaction between the cyber and physical aspects of the CPS system and that this should be within the primary domain knowledge of the CPS engineer.

4. Required knowledge and skills

4.1 Proposed cyber-physical system curricula

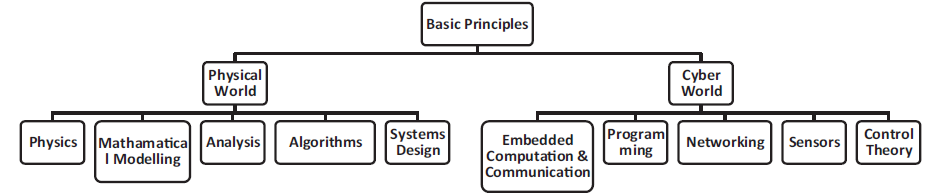

In 2016, the US National Academy of Sciences conducted a study on the need for CPS education and prepared guiding CPS education content.

Based on workshop feedback from academia and industry, the report strongly promoted the introduction of university programmes in CPS, recommending three broad areas of content: (1) principles of CPS, (2) foundational skills and (3) system characteristics.

The first area concerns physics, mathematics, sensor technology, data/signal analysis and control theory as the basis for the components of cyber and physical.

Foundational skills are mostly associated with the principles above but concerned with practical implementation; they focus strongly on the numerical and computational aspects, although do include modelling of dynamic, heterogeneous systems as an important element.

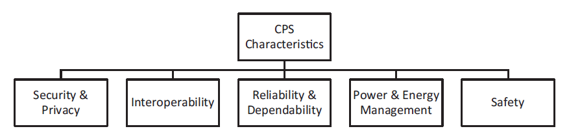

System characteristics are largely concerned with aspects that systems engineers would more generally refer to as speciality engineering: safety, security, stability, human factors, etc.

4.2 Cyber-physical system education: knowledge mapping

The report [28] provides a detailed curriculum map for CPS and lists the US degree programmes that comply with it to some extent.

The subjects presented focus on technical systems and only partially address societal matters.

The following draws on and expands the curriculum map proposed by the US National Academy of Sciences.

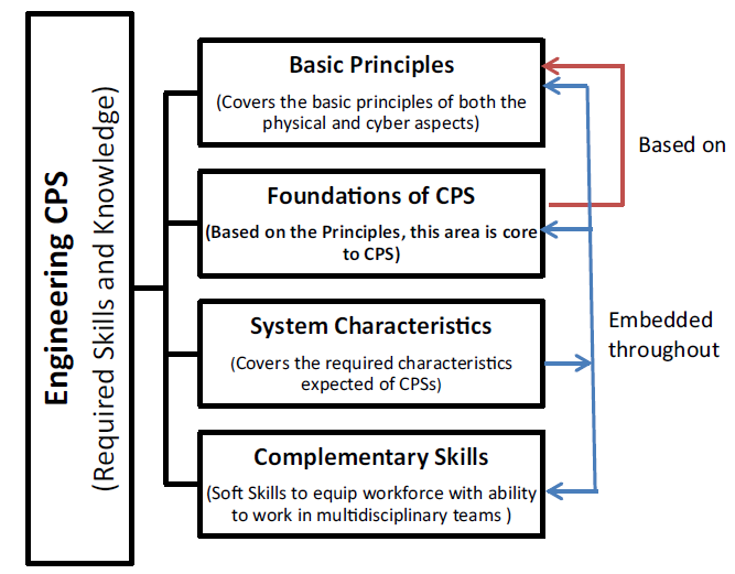

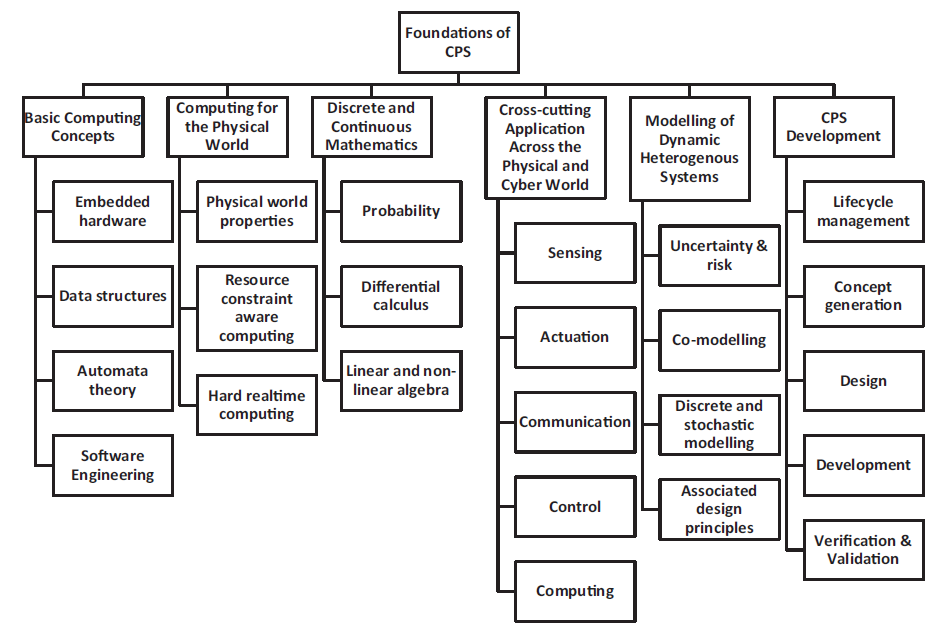

The skills for engineering CPS are summarised in Fig. 9.3: these are broadly the skills that one would expect to meet in a systems engineer but with a particular focus on the integration of cyber and physical aspects.

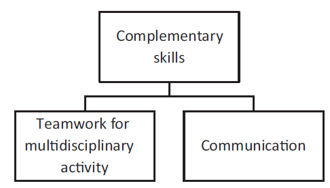

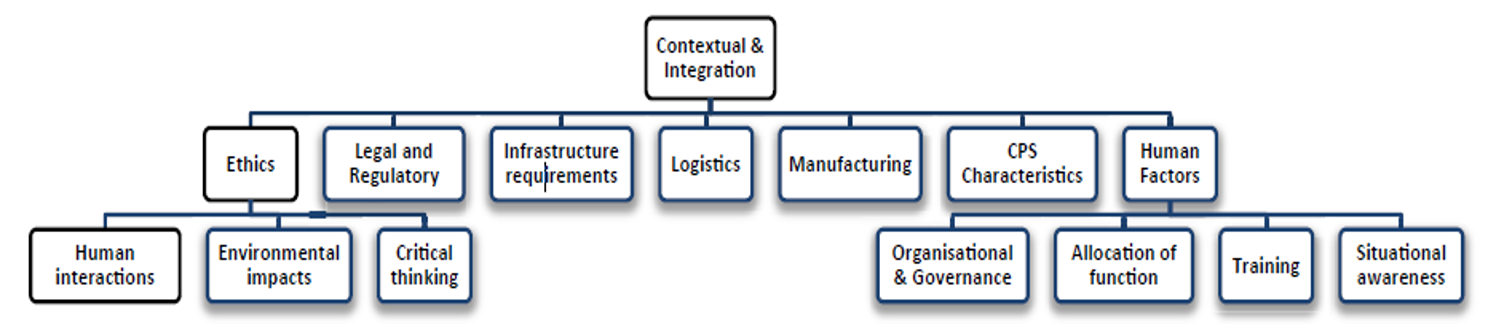

The four skills are broken down further in Figs 9.4e9.7.

However, these are not sufficient to cover all required areas, and Fig. 9.8 indicates additional areas about which the CPS developer must have some knowledge.

Figure 9.3 Four interdependent subject areas for engineering cyber-physical system (CPS).

Figure 9.4 Basic principles for engineering cyber-physical system (CPS).

Figure 9.6 Cyber-physical system (CPS) characteristics.

Figure 9.6 Cyber-physical system (CPS) characteristics.

Figure 9.7 Complementary skills.

Figure 9.8 Contextual and integration considerations for cyber-physical system (CPS).

4.3 Wicked problems

Except for the simplest systems, CPSs are generally classified as a subset of a class called systems of systems and these are very often described as posing ‘wicked problems’.

Wicked problems are complex, they have no definitive formulation, no stopping rule, and very often the solutions cannot be described as good or bad.

A TCPS can be considered at many levels of abstraction, but if we assume that it involves multiple interacting elements, then it has many of the characteristics of a wicked problem.

There is no curriculum for wicked problems, but there are personal attributes that equip an individual better or worse for managing a wicked problem.

In particular, a tolerance of ambiguity is an asset when trying to deal with such problems.

The education and training for TCPS should, therefore, encourage students to develop a mindset that can appreciate and manage wicked problems; this mindset is likely to be particularly engendered through appreciation of the social and creative professions quadrant in Fig. 9.9.

Figure 9.9 Classification of Transportation Cyber-Physical System disciplines using [15] framework as reconfigured by [16]; shading indicates nonlife, life or both along the third axis.

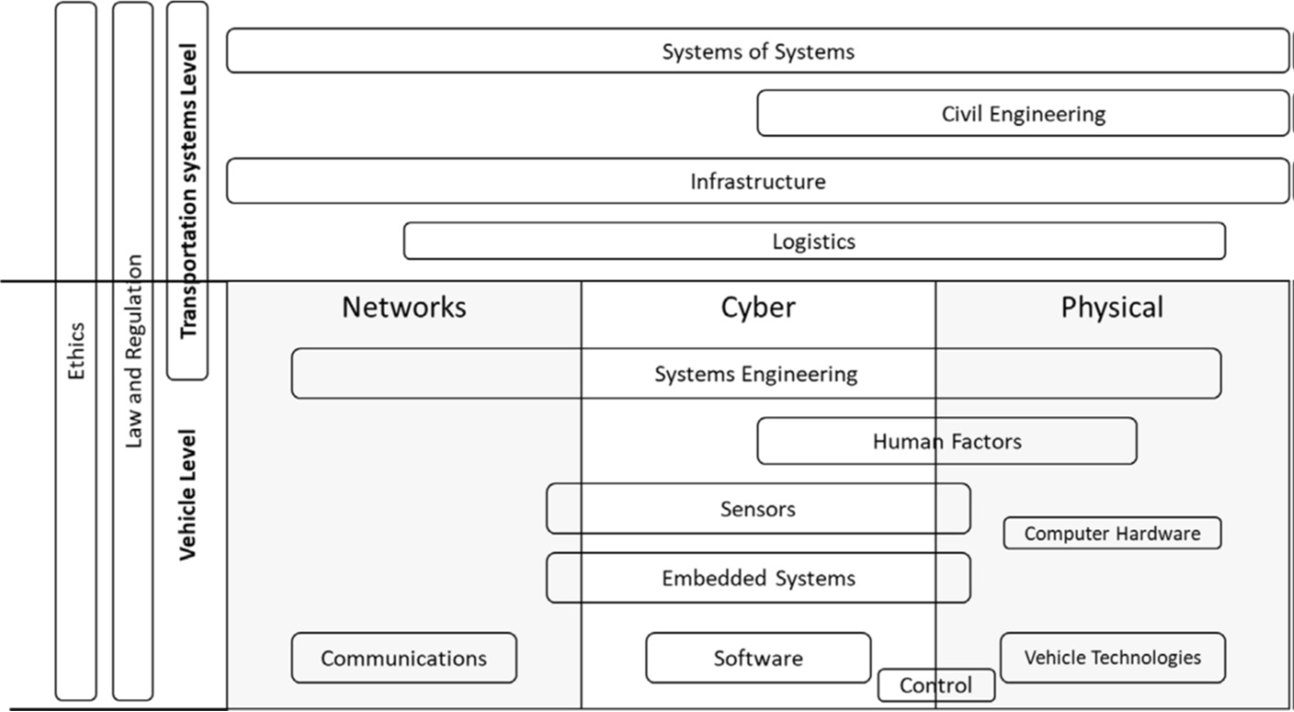

4.4 Key disciplines for Transportation Cyber-Physical System curriculum

Figure 9.10 Key components of a Transportation Cyber-Physical System curriculum for degree and graduate-level study.

Figure 9.10 Key components of a Transportation Cyber-Physical System curriculum for degree and graduate-level study.

5. Curriculum delivery mechanism

- The curriculum can be delivered through a variety of mechanisms and these are summarised below:

- Short courses: Such courses can be delivered over a few days or a few weeks depending upon breadth and depth each course is designed to cover.

- Undergraduate degrees: Most of the currently available courses in TCPS (as well as those being planned) fall into this category. Ideally, an undergraduate course in TCPS should cover the entire life cycle of systems development, including idea generation, design, modelling and simulation, verification and validation, development and deployment.

- Postgraduate degrees: Such degrees are from first level to doctoral level and are either offered as full time or part time; most generally, they are masters’ level by teaching. Curricula within these programmes may include research and development projects further advancing the field of TCPS and should preferably be in collaboration with relevant industry.

- Apprenticeships: Apprenticeship is a form of on-the-job training which may include an element of classroom study leading to a recognised qualification. An apprentice must be above 16 years of age and the duration of an apprenticeship is usually between 1 and 5 years.

- Continuing professional development: This is a means by which employees continue to learn and develop either formally or informally as they work. This could include academics, people working in TCPS industry and administration undergoing short courses, workshops or trainings in order to gain lacking TCPS skills.

- Certificate courses: Certificate courses can be developed and offered by academia with or without collaboration with relevant industry.

- Distance learning or remote learning: This form of education delivery does not require students to be physically present in a traditional educational setting.

- Secondments: Given the clear need for hands-on experience, secondments from universities into relevant industries (and vice versa) provide an essential part of curriculum delivery.

- On-the-job training: Staff can gain new skills and knowledge through in-house or on-the-job training.

6. Conclusions

TCPS comprises complex systems, the development and operation of which rely on skills from many different disciplines.

It has become evident that many engineers working in TCPS have inadequate software skills to satisfactorily address the needs of current systems, which have significant embedded software.

The highly connected nature of TCPS means that modern developers must have a wide knowledge of the contributing disciplines, because failure to have breadth of understanding will likely lead to faults or unintended emergent behaviours.

Ideally, students educated in TCPS will have a T-shaped CV, which implies that they will have competent broad knowledge across a range of relevant topics, together with an indepth knowledge of one or two areas.

Universities have traditionally taught in single disciplines or in domains in which few disciplines need to be studied in depth.

CPS challenges that approach by requiring curricula that include many disciplines, but to be taught effectively, a transdisciplinary approach-in which every team member has a competent understanding of all relevant disciplines-is needed.

Most importantly, students should develop an holistic view of the system to be engineered and so the degree and masters’ course for TCPS must go beyond the imparting of knowledge only, but develop the outlook and holistic appreciation of the students.